For decades, the dominant narrative of queer life in the West has focused on “coming out of the closet.” This metaphor suggests a linear journey from a dark, restrictive place (secrecy) to a liberated, open existence (pride). While this model has empowered millions, it often fails to account for the complex realities of Black, Brown, and non-Western queer individuals for whom “full visibility” can be dangerous or culturally dissonant.

Daniel Nkado’s Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD) of 2025 offers a fresh perspective. This recently proposed framework moves away from the binary of “in vs. out” toward a strategy of continuous negotiation.

This article explores the Model of Dynamic Disclosure in depth, providing a comparative analysis against established psychological frameworks (Cass, D’Augelli, and Fassinger) to help readers understand the shifting landscape of LGBTQ+ identity management.

The Reality of Risk: Why New Queer Models Matter

To understand why the Model of Dynamic Disclosure is necessary, we must examine the data on intersectionality and safety. The traditional imperative to “come out” assumes a level of safety that not all queer people have equal access to.

a. Disproportionate Risk: In the United States, Black LGBTQ+ people experience higher rates of violent victimisation and housing discrimination than white LGBTQ+ people.

b. Mental Health Context: The Trevor Project’s 2023 survey found that 41% of LGBTQ+ youth (13–24) seriously considered suicide in the past year, and while 54% reported depressive symptoms overall, rates were higher among Black LGBTQ+ youth (56%) than white peers (50%).

c. Global Context: In over 60 countries, consensual same-sex relations are still criminalised. In these environments, the Western ideal of “being out” is not just culturally foreign but also a legal and safety liability.

It is within this high-stakes context that Nkado’s model emerges—not as a rejection of pride, but as a survival manual for navigation.

Deep Dive: Nkado’s Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD)

Developed by Daniel Nkado, the Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD) describes how Black gay men (and by extension, other marginalised queer groups) manage visibility. Unlike older models that view “the closet” as a shame-filled place to escape, MDD views disclosure as a spectrum of choices tailored to safety and survival.

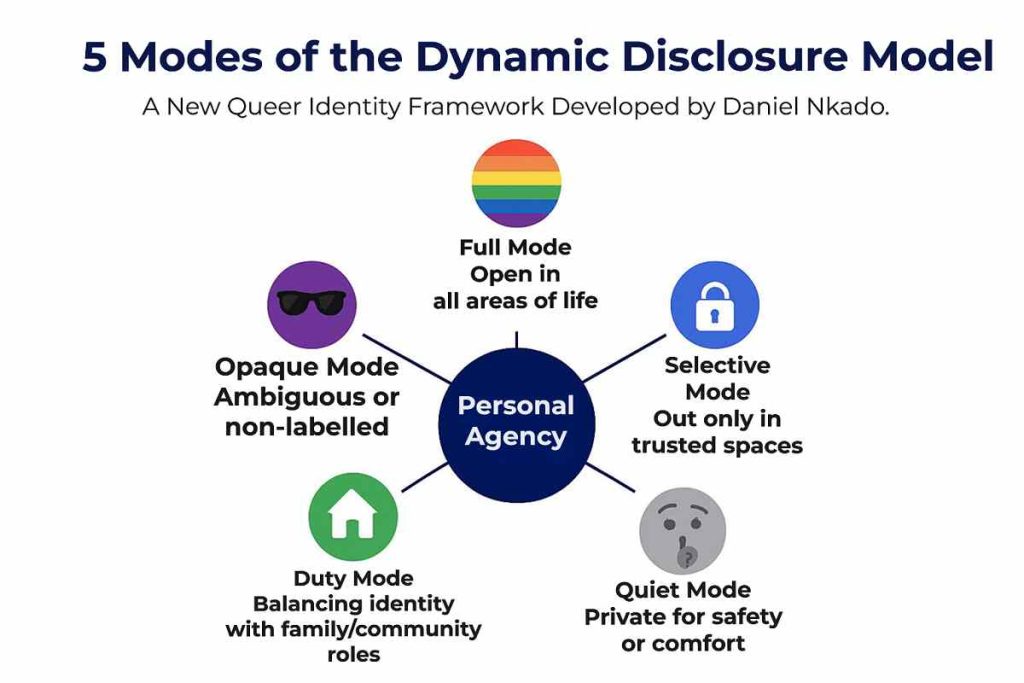

The model proposes five distinct “Modes” that an individual can adopt, switch, or combine depending on their environment:

1. Full Mode 🌈

- Definition: Being completely open about one’s queer identity in all realms of life.

- Context: This aligns with the Western ideal of being “out.” It usually occurs in environments where the individual feels physically safe and legally protected.

2. Selective Mode 🔒

- Definition: Disclosing only in specific safe spaces or to trusted individuals.

- Context: A person might be out to their university friends or inner circle but remain guarded with extended family or employers. This is a strategic compartmentalisation to maintain support systems while mitigating risk.

3. Quiet Mode 🤫

- Definition: Choosing to live with a high degree of privacy or “invisibility.”

- Context: This is often a rational response to danger. For example, a queer person living in a region with anti-sodomy laws may adopt Quiet Mode for self-preservation. It is not necessarily “internalised homophobia,” but rather a calculation of safety.

4. Opaque Mode 🕶️

- Definition: Neither confirming nor denying one’s queerness.

- Context: This involves embracing ambiguity. An individual allows others to speculate but refuses to label themselves explicitly. It effectively neutralises the weaponisation of their identity by refusing to hand over a “confession.”

5. Duty Mode 🏠

- Definition: Prioritising familial or cultural duties over open disclosure.

- Context: This creates a tension between personal identity and communal responsibility. For example, a man might enter a heterosexual marriage to satisfy cultural expectations of procreation while privately maintaining a queer identity. In collectivist cultures, “duty” often supersedes “individualism.”

Nkado emphasises honesty with immediate partners—such as a spouse or co-parent—as a priority within Duty Mode for safety. This transparency prevents harm, supports informed consent, and clearly distinguishes Dynamic Disclosure from deceptive or exploitative secrecy.

Core Pillars of the MDD Framework

The Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD) is defined by three specific characteristics that differentiate it from its predecessors:

1. Non-Linearity

Traditional models suggest a ladder: you start at the bottom (closeted) and climb to the top (out). Nkado’s model is a dashboard. A Black gay man might operate in Full Mode with friends, Quiet Mode at work, and Duty Mode at a family gathering—all in the same week. This fluidity reflects the mental agility required to navigate hostile spaces.

2. Safety as a Priority

The model reframes silence. In older psychological frameworks, staying in the closet was often pathologised as “cowardice” or “immaturity.” MDD reframes it as a survival strategy.

As the framework’s introductory page on DNB Stories Africa notes, “for many, silence is a survival strategy—not a lack of courage” (Nkado, 2025). Naming silence this way can ease the internal shame many people carry when full visibility isn’t safe or possible.

3. Agency and Control

The central innovation here is Agency. The model empowers individuals to be the architects of their own visibility. By validating Opaque or Selective modes as success strategies, this approach removes pressure to follow a Western blueprint that doesn’t fit their cultural reality.

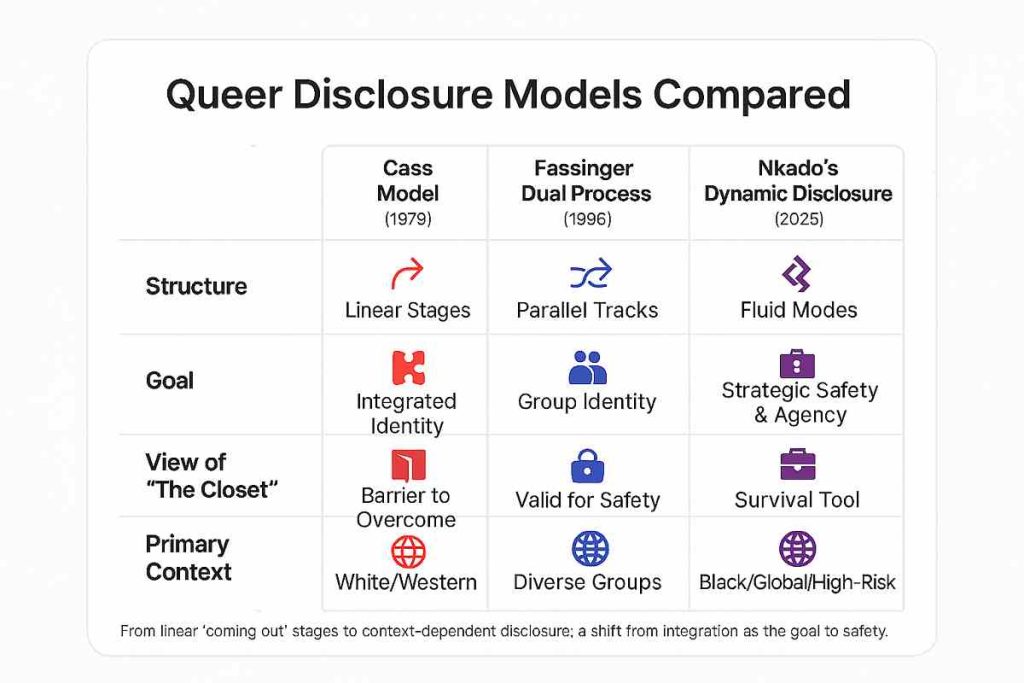

Comparative Analysis: MDD vs. Established Models

To assess MDD’s place within the history of queer psychology, we must compare it with the “Big Three” identity development models.

1. The Cass Identity Model (1979)

- The Theory: A six-stage linear model moving from Identity Confusion to Identity Synthesis[1].

- The Vibe: “The only way out is through.”

- Comparison: Cass views the “closet” as a hindrance to identity synthesis. MDD argues that, for some, the closet serves as a shield. While Cass emphasises internal psychological consistency, MDD emphasises external sociological safety.

2. D’Augelli’s LGB Lifespan Model (1994)

- The Theory: A human development perspective that views identity as a lifelong process influenced by social contexts[2].

- The Vibe: “Identity is a marathon, not a sprint.”

- Comparison: D’Augelli introduced the idea that environment matters. However, MDD takes this further by specifically addressing the racial and cultural specifics of that environment, particularly for Black men navigating masculinity and racism.

3. Fassinger’s Inclusive Dual Process Model (1996)

- The Theory: Separates the process into two parallel tracks: internal individual identity (self-acceptance)[3] and external group identity (community membership).

- The Vibe: “You can be okay with yourself without being an activist.”

- Comparison: Fassinger is the closest predecessor to Nkado’s Model of Dynamic Disclosure because it acknowledges that one can be internally healthy without being publicly vocal. However, MDD introduces specific, actionable “modes” (e.g., Duty Mode) that describe how to manage that disconnect, particularly in non-Western contexts.

Summary Comparison Table

| Feature | Cass (1979) | D’Augelli (1994) | Fassinger (1996) | Nkado (MDD) (2025) |

| Structure | Linear Stages | Lifespan Processes | Dual Tracks (Private/Public) | Fluid Modes |

| Goal | Integrated Identity | Identity Fulfillment | Group Membership | Strategic Safety & Agency |

| View of “The Closet” | A barrier to overcome | A starting point | Valid for public protection | A tool for survival |

| Primary Context | White/Western | Social/Lifespan | Diverse Groups | Black/Global/High-Risk |

Critical Assessment: Strengths and Limitations of MDD

Strengths

- Destigmatization: By labelling non-disclosure as “Quiet Mode” or “Duty Mode,” the model reduces the stigma associated with being “closeted.”

- Inclusivity: It aligns with E. Patrick Johnson’s “Quare” theory, inserting race and culture into the centre of the conversation rather than treating them as afterthoughts.

- Pragmatism: It offers practical strategies for the 42.7% of Black LGBTQ+ youth who report feeling unsafe in at least one school setting (HRC, 2024), validating their need for caution.

Limitations

- Lack of Empirical Data: As a 2025 conceptual framework, MDD is a theoretical tool. It lacks the decades of longitudinal studies that back Cass or Fassinger.

- Potential for Misuse: Critics might argue that “Duty Mode” could be used to justify remaining in oppressive situations longer than necessary, potentially delaying personal self-actualisation.

Areas for Growth

As a 2025 framework, MDD is primarily an analytic tool. Unlike the Cass or Fassinger models, which have been tested over decades, MDD lacks extensive empirical data regarding long-term mental health outcomes. Additionally, while it excels at describing the experience of Black gay men, further work is needed to see how these modes apply to transgender and non-binary individuals, where “visibility” involves different physical and social dynamics.

Conclusion

Traditional models, such as Cass’s, taught us that coming out is a journey of courage. Later models, like Fassinger’s, taught us that this journey is complex. Daniel Nkado’s Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD) teaches that the process is ours to control.

By shifting the focus from “coming out” to “managing disclosure,” MDD validates the daily reality of millions of people who balance identity and safety. It confirms that silence is not always a lack of pride—sometimes, it is the ultimate form of self-preservation.

For Black queer men and others navigating the intersection of racism, homophobia, and cultural expectation, MDD offers a liberating vocabulary. It shifts the question from “Why aren’t you out?” to “Which mode is keeping you safe and authentic at the moment?” In a world that is still hostile to difference, this shift from visibility to agency is not just theoretical—it is essential.

Frequently Asked Questions

References

- Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/j082v04n03_01

- D’Augelli, A. R., Hershberger, S. L., & Pilkington, N. W. (1998). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(3), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080345

- Fassinger, R. E., & Miller, B. A. (1997). Validation of an Inclusive Modelof Sexual Minority Identity Formation on a Sample of Gay Men. Journal of Homosexuality, 32(2), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1300/j082v32n02_04

- Human Rights Campaign (HRC). (2024). Black LGBTQ+ Youth Report: https://hrc-prod-requests.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/2024-Black-LGBTQ-Youth-Report.cleaned.pdf

- Johnson, E. P. (2001). “Quare” studies, or (almost) everything I know about queer studies, I learned from my grandmother. Text and Performance Quarterly, 21(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930128119

- Nkado, D. (2025, December 31). Why Black Gay Men Don’t Have to “Come Out” Like Other Races – DNB Stories Africa. DNB Stories Africa. https://dnbstories.com/2025/12/black-gay-men-coming-out-framework.html

- Pachankis, J. E., Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2015). The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 890–901. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000047

- The Trevor Project. (2023). 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People. The Trevor Project. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2023/