A comparative analysis of LGBTQ+ life in Nigeria and the UK—this piece explores how increased safety can quietly weaken intimacy, and how dating apps—Grindr, Jack’d, and others— in low‑risk environments often transform communal bonds into patterns of consumption.

Scope Note: This analysis focuses on Black gay cis men—I acknowledge that the experiences of queer women, trans people, and other groups may differ significantly.

- 1. Intro: The Quiet Struggle of LGBTQ+ Africans

- 2. Danger Outside, Refuge Inside: How Queer Nigerians Survive

- 3. Queer Elders in Nigeria: Memory, Mentorship & Survival

- 4. Gay Relationships, Intimacy and Sexual Desire in Nigeria

- 5. UK Black Gay Experience: Safety Gained, Intimacy Lost

- 6. UK Gay Hookup Culture and Transactional Sex

- 7. Performance, Dissonance & Leaky Feelings in Gay Men

- 8. Time Wasting in the UK Gay Scene: Sex as ROI

- 9. Nigeria vs. UK: How Context Shapes Queer Desire

- 10. Rebuilding Trust and Intimacy in UK Queer Spaces

- 10. Conclusion: Rebuilding Love in the West

- References

1. Intro: The Quiet Struggle of LGBTQ+ Africans

Queer life in Nigeria has long been narrated through what people cannot safely name in public. This is a tragic paradox because Nigerians are not, by nature, a silent people. The suppression of colour, humour, argument, and tenderness is not a matter of temperament, but a survival response to the steady threat of policy, policing, and social consequence.

a. Understanding the SSMPA: Nigeria’s Anti‑LGBT Law

A defining moment for contemporary queer life in Nigeria came on 7 January 2014, when President Goodluck Jonathan signed the Same‑Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (SSMPA) [2].

The SSMPA transformed street homophobia into government policy, but it did not invent the hostility—gay Nigerians had long faced public harassment, prejudice, and violence. What the SSMPA did was amplify fear and endorse hatred. It told the haters, “Go on, we are behind you.”

b. How the SSMPA changed life for LGBTQ+ Nigerians

Before 2014, “kito”—blackmail and extortion schemes—existed, but perpetrators operated with caution. The legal atmosphere held enough ambiguity that some brave victims could report attackers to the police. In some cases, the attacker was arrested and held in a cell for a day or two. That small disruption, as limited as it was, counted as something.

After the SSMPA, the social meaning of reporting a crime shifted. With the law explicitly positioning the state against the queer individual, the aggressor’s confidence grew. As noted by Amnesty International (2014)[1], the law created a “witch-hunt” atmosphere. When a law is widely read as “the state is on my side,” perpetrators act with impunity, courage drains from victims, and silence becomes the only safe refuge.

2. Danger Outside, Refuge Inside: How Queer Nigerians Survive

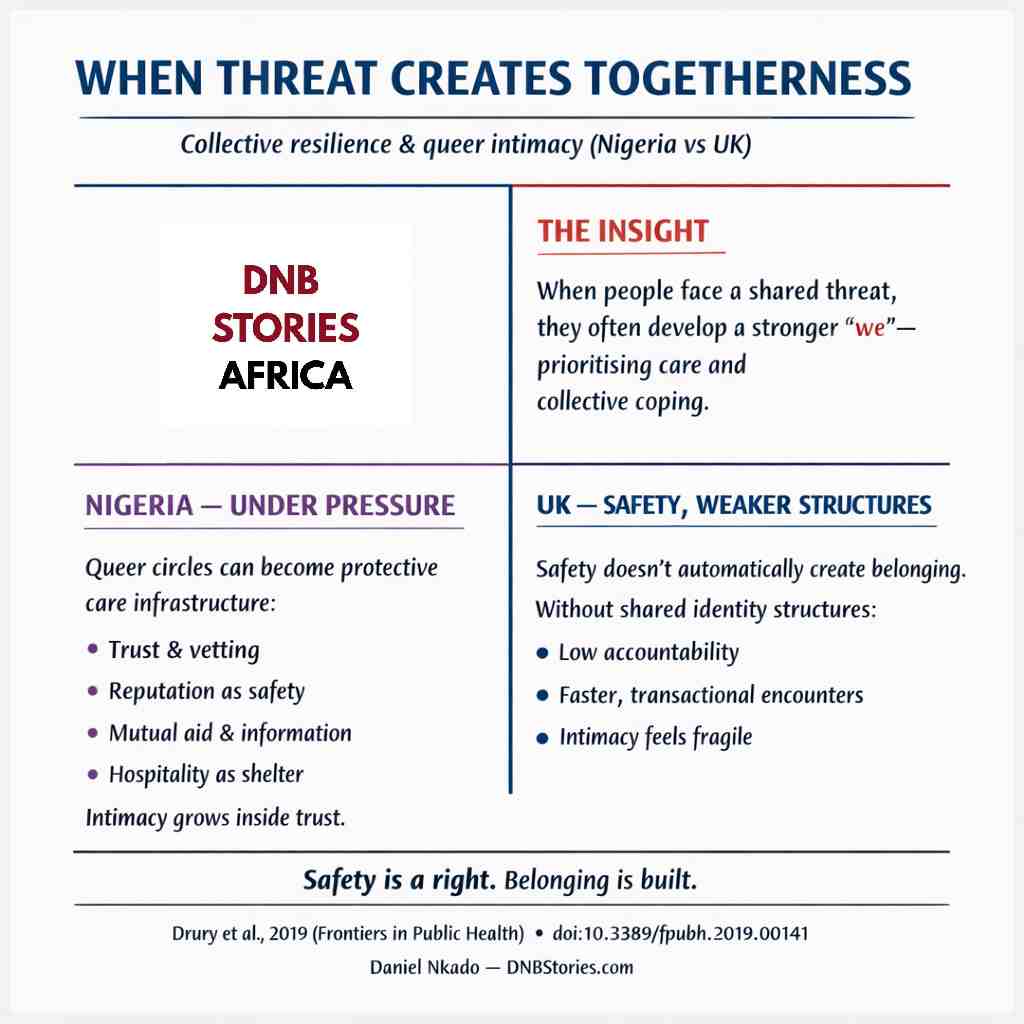

In Nigeria, the external environment for queer people is marked by high pressure[3]—hostile legislation, police harassment, and the constant threat of exposure. Yet, just as multiple studies on group threat and social identity have shown, when a community faces credible external danger, shared identity and internal cohesion can intensify. Victims coordinate trust and mutual protection to increase safety.

In Nigeria’s queer underground, I witnessed this dynamic firsthand: networks of mutual aid, discreet social rituals, and quiet solidarities formed an informal welfare system, helping people find safety, information, and emotional support in a society where public institutions produced more risk than care.

Research on collective resilience shows that when people face a shared threat, they often develop a sense of togetherness that prioritises care and collective coping. This helps explain why Nigerian queer circles evolved into protective care infrastructures under pressure — and why UK safety, without shared identity structures, can leave intimacy feeling fragile.

While these care structures build collective resilience, they do not erase the profound harms of the SSMPA and the pervasive societal violence faced by queer Nigerians.

a. Care Over Judgement: The Underground Ethic of Queer Survival

Most Nigerian gay spaces held an unwritten rule: Don’t add to another gay person’s burdens.

This is not to pretend that everyone acted like a saint or that the community had no internal problems. It wasn’t a utopia—serious class tensions existed, and also femophobia: this is usually driven by fear of being outed through association with feminine men, rather than a simple hatred of femininity. We, as African gay men, were never ashamed of colour.

b. Femininity in Nigeria’s LGBTQ+ Landscape

The dominant markers of social value in Nigerian queer spaces are education, career success, natural intelligence, family wealth or connections, integrity, humour, talent and initiative—a femme‑presenting gay man who holds any of these is more likely to be invited than a macho top offering none of them.

In underground queer networks, femme men shone — their grit, wit, empathy, and sparkle lit up the room.

In private spaces, people often melted into a relief of carefree expression. Those who presented as masculine were genuinely masculine—yet you might still watch them, coached by an ever-hard-to-please femme friend, practising a strut in imaginary heels or perfecting choreography to Beautiful Liar. The scene was playful and tender: performance as rehearsal, friendship as training, and joy as a small, defiant freedom.

3. Queer Elders in Nigeria: Memory, Mentorship & Survival

Where legal protections are absent, personal character becomes the primary safeguard—integrity and trustworthiness function as a kind of social currency.” Anyone known for “kito,” lying, or setting people up is swiftly ostracised.

a. Age and Wisdom: The Role of Queer Elders in Community Life

Older men were expected to embody steadiness. A forty-year-old engaging in deception or performance for status drew disbelief, not just annoyance.

Age mattered—not as a tool for shaming, but as a marker of respect, responsibility, and the expectation of reliability. When an older man acted carelessly or in folly, the community’s rebuke often took the form of a moral question: “Is this what you expect these young kids to be learning from you?”

4. Gay Relationships, Intimacy and Sexual Desire in Nigeria

In Nigeria, desire moved at its own careful pace. Arranged meetings stretched across weeks and months, and in that waiting, something tender often formed: jokes, confidence, small rituals of care—friendship quietly braided into longing.

Despite Nigeria’s harsh environment, the culture places a high value on early self‑discovery and authentic living. Individuality is nurtured, often shaped by the example of older brothers and respected mentors. This early grounding in who you are makes it easier to recognise and appreciate genuine connection. Time spent talking, eating, laughing, and co-creating—more than sex—became the clearest markers of intimacy.

a. Intimacy and relationships in the Nigerian gay community

Nigeria’s risky environment and the cultural weight attached to sex make queer intimacy more selective and profound, which is why “he just wants sex” can legitimately end a relationship.

i. Legal and safety risks make trust costly; time together verifies character and mutual protection before moving forward.

ii. In Nigerian queer communities, proximity to straightness carries little social capital—if any. Many gay men reject heteronormative validation and embrace a counter‑pride that frames queerness as competence, distinct intellect, and creative power.

That said, local gay culture upholds the wider “respect of body” or “bodies as temples” ethic, so sexual intimacy is carefully policed and granted only to those judged worthy.

Enjoying this analysis? Join the DNB Community on Telegram or subscribe to our weekly newsletter for more deep dives into queer culture, migration, and the sociology of intimacy.

5. UK Black Gay Experience: Safety Gained, Intimacy Lost

Moving to the UK brings profound relief—the freedom of no longer living under state‑sanctioned threat. Suddenly, “Are you sure you’re not gay?” shifts from a setup for extortion into harmless banter.

This freedom was contagious at first. UK gay nightlife dazzled: at Bootylicious, a stern poster warned that homophobic behaviour would not be tolerated; at Club Fire, real drag queens danced onstage. I filmed bits and sent them to a friend in Nigeria—another drag‑obsessed buddy like me.

“Did RuPaul come too?” he asked, his excitement edged with longing—a reminder of the distance now sitting quietly between us.

Suddenly, I didn’t just feel fully human; I felt empowered enough to call someone out on a bus: ‘Did you just look at me homophobically?’

a. Emotional Disconnection in UK Black Gay Spaces

Yet before the exhilaration could settle, a different kind of isolation revealed itself—subtle at first, then unmistakable. You see and meet people here—too many, even—but you don’t always get the same depth of knowing. It’s less about the pattern itself and more about the lack of interest—the lack of effort.

While pockets of deep, sustaining community certainly exist within the UK Black gay scene—particularly among older subcultures—my critique addresses the prevailing gaps in the dominant culture, rather than dismissing every individual experience.

Migration to the UK—often imagined as an escape from both oppression and suppression—introduces another complicated reality: safety does not come alone. The UK offers legal protection and far less structural hostility, yet it also brings new social pressures. Status anxiety, relentless performance culture, and fragmented community life can surface in ways that leave some migrants feeling almost as isolated as they were in the environments they fled.

Research into LGBTQ+ mental health in the UK consistently shows that, despite advancements in legal equality, high levels of loneliness and poor mental health persist within gay communities (see, for example, Stonewall’s 2018 health report).

b. Self‑policing Among Black Gay Men in the UK

Black gay men born in the UK live in physical safety, but many still navigate a culture that restricts genuine self‑expression—external freedom vs internal restriction. The world says “be open, live freely,” yet the inner self continues to police expression, desire, and truth.

Black gay men frequently navigate intersecting stigmas that encourage internal self‑policing. A good example is the adoption of “straight‑acting” behaviours as a coping strategy against homophobia. These performative mechanisms—aimed at reducing rejection from both Black communities and the broader LGBTQ+ sphere—build into a conflict in identity. As a result, authentic self‑expression and the potential for deep emotional connection deteriorate. People meet, have sex, but do not really see or know each other.

6. UK Gay Hookup Culture and Transactional Sex

The fundamental shift in intimacy between Nigeria and the UK isn’t really about how people meet; it’s about what people are looking for. From listening to countless community stories, studying the social dynamics, and comparing them with existing research, a clear pattern emerges.

In the UK, where physical safety is more guaranteed, sex often serves two major functions—and neither of these has much to do with intimacy.

a. Sex as a Coping Mechanism Among Gay Men in the UK

Existential loneliness—a profound sense of separateness and disconnection—is a major problem in the UK. One qualitative study found that 83% of participants have experienced it at some point. Unlike social loneliness, this pervasive feeling persists even in crowds and is often tied to mental health issues, ageing, and feeling forgotten or undervalued (McKenna-Plumley et al., 2023).

For many UK gay men (UGM), sex operates as a regulatory mechanism, functioning like a drug—a quick dopamine hit that temporarily masks feelings of isolation. This reliance on sex often grows out of attempts to manage stress, loneliness, or emotional pain, a pattern consistent with Emotion Regulation Theory. Sexual encounters may offer brief distraction and pleasure, but they rarely touch the deeper issues of rejection, anxiety, or low self‑worth that drive the behaviour in the first place.

b. UK Gay Culture: Performance, Status and Sex as Proof

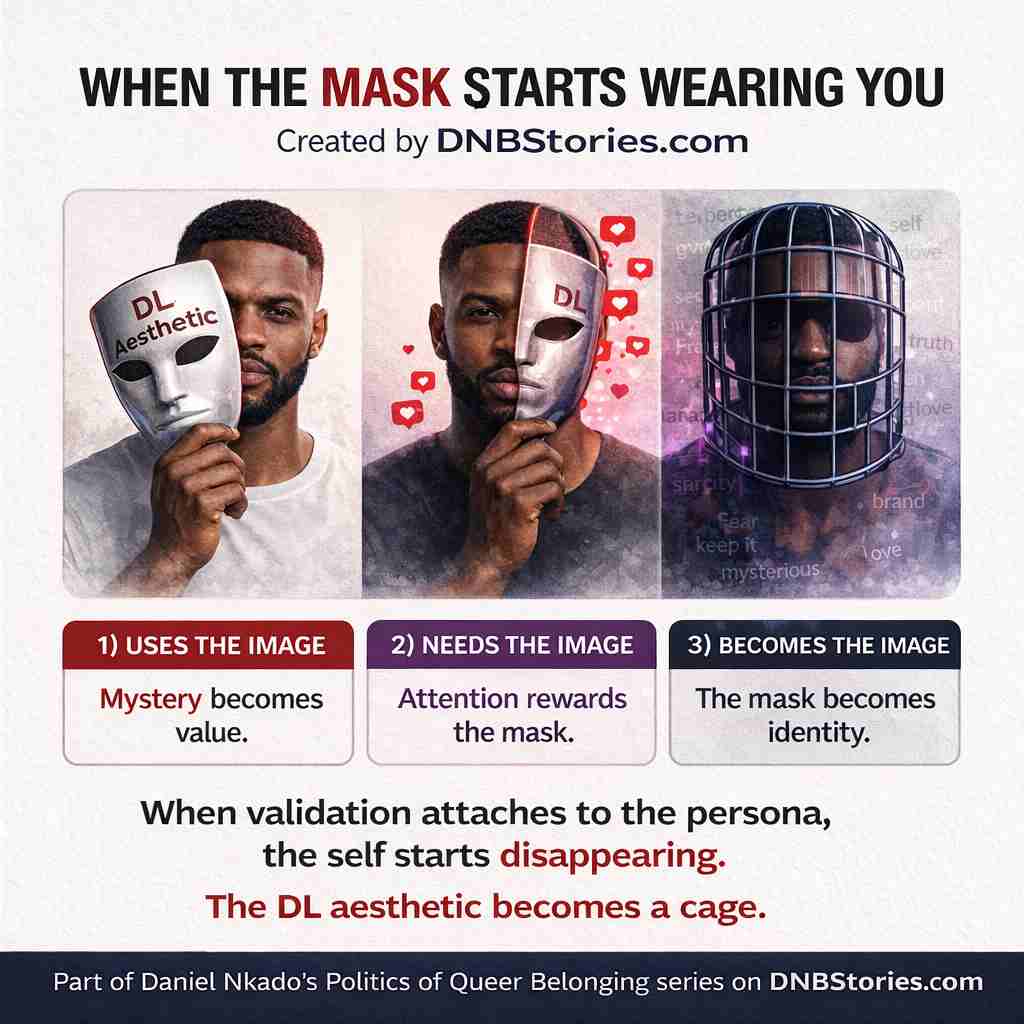

In a culture built on hierarchies and constant posturing—the strategic editing and presentation of self—sex becomes a form of proof of rank or status.

Using sex as confirmation of value echoes an older logic rooted in slavery and racial capitalism, when enslaved Black people’s bodies were commodified, and their worth was measured through physical and sexual availability rather than their full humanity.

- A macho performer uses sex to measure his standing: the higher the partner’s status, the bigger the flex. He seeks group settings where high‑status signals are concentrated so he can rack up as many status hits as possible.

- A “Dom Total Top” performer gauges his rank by how many people are willing to submit to him. He doesn’t want “easy bottoms”—the harder the chase, the deeper the payoff.

During sex, attention shifts from the partner to the payoff—will this raise my status or lower it? Status drives sex, not character and person.

Example: A Black gay man in London—call him Oxas—keeps sleeping with Joban because Joban sells himself as a “macho total top” and performs it convincingly. Oxas isn’t really attracted to Joban’s inner life; he’s attracted to the symbol Joban performs. You can’t build a partnership with a label. When desire is attached to a role, the relationship collapses the moment the performance slips—or the fantasy gets bored.

7. Performance, Dissonance & Leaky Feelings in Gay Men

Performance can buy short-term acceptance, but over time it produces emotional incongruence—a gap between the authentic self and the performed self that can lead to emotional leakage. This gap runs on anxiety. The performer becomes hyper-vigilant about “breaking character,” which encourages heavier self-editing and a fear of vulnerability, because he assumes that the moment he becomes real, he’ll be rejected.

So anytime the performance slips—say a man who brands himself as a “total top” on Grindr decides to bottom—he may experience an unpleasant internal state similar to stress, guilt, or self-disgust. It’s not the act itself that harms him; it’s the collision between his true desire and identity branding. Over time, this conflict compounds the already existing minority stress, worsening the overall outcome.

a. How Status and Performance Fuel Shaming in Black Gay Spaces

A performance‑driven environment produces a culture of shaming and utility by turning people into competitors. Sometimes the person closest to your aesthetic becomes your biggest rival—what should have been a point of connection becomes a tool of separation.

When everyone assumes everyone else is performing—using one another for status management and elevation—sex collapses into a quick grab for orgasm and nothing more. In that landscape, people can sleep with someone they actively dislike and feel nothing about it. The body becomes a tool, used rather than met. Connection is replaced by utility.

8. Time Wasting in the UK Gay Scene: Sex as ROI

On Grindr, a profile posts a clear warning: “No time wasters.” This is a signal of transactional expectation: the time spent must produce a predictable outcome.

This dynamic exposes a painful pattern in the UK gay scene that often confuses newcomers: sex gets treated like an investment, and kindness is met with suspicion—or even rejection.

In a relational culture—like Nigeria’s underground—if you invite someone over, offer them food, drinks, and good conversation, but sex doesn’t happen, the evening is still seen as a success. You made a friend; you practised hospitality.

In the UK’s consumption culture, that same scenario often ends in being blocked.

9. Nigeria vs. UK: How Context Shapes Queer Desire

The contrast isn’t that Nigeria is “better” — no one wants to live under the threat of jail. That country gave me more pain and trauma than anyone should have to carry, and I’m still healing from it in layers.

However, when it comes to intimacy between two queer men, the social logic of the two environments is radically different. The UK offers far more opportunities for encounters — a high quantity delivered in fast, disposable bursts. The real distinction lies in the quality of connection and the meaning attached to the act (Pronk & Denissen, 2019)[5].

In Nigeria, amid widespread hostility, recognition becomes a silent agreement—a shared glance or brief smile that offers momentary warmth and acknowledges mutual vulnerability. In the UK, sex often functions as a temporary escape from loneliness or boredom—the fix—or as a way to affirm one’s place within an unspoken status hierarchy—the flex. Once the sensation fades—or when the possibility of genuine connection appears—many withdraw out of fear of vulnerability. The pursuit is for a feeling, not a person.

a. Queer Desire in the West: Sex for Escape or Status

i. For escape seekers: The moment sexual contact ends—or is absent—the high fades, and the other person becomes a reminder of the void. That’s why people can be cold right after intimacy: they’re coming down from the high and want to disengage.

ii. For status seekers: Interest evaporates the moment you show you like them; there is no flex here, so they chase it elsewhere.

The game players—seekers—know how to work these dynamics to their advantage to get what they want. The novices don’t know what’s going on. A subgroup of game masters plays the players, leaving them in delusion. Which are you?

An upcoming article will provide an in-depth exploration of this pattern—mapping its root causes, how it shows up in hookup dynamics, and the management strategies people can use for self-protection and harm reduction.

b. Comparative social logics: Nigeria vs. the UK

Environment doesn’t just change how people meet — it reshapes what intimacy means: Nigeria’s high‑risk, conservative context makes trust, patience, and character the basis of connection, while the UK’s low‑risk abundance speeds desire into transactional, disposable encounters.

| Feature | Nigeria | The UK |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Social Logic | Solidarity. External threat drives internal cohesion and mutual care. | Optimisation. Safety enables a culture of utility and sex as validation. |

| Environmental Friction | High friction. Safety risks and logistics require vetting. | Low friction. Apps and safety enable constant, connection-less sex. |

| Role of Intimacy | Communion. Connection is nourishment. | Consumption. Sex is a coping mechanism or “fix” for stress or a marker for value. |

| View on Hospitality | Valued. Offering food and conversation is a success even without sex. | Used primarily for safety, avoiding threats and exposure. |

| Social Currency | Character. Education. Career. Integrity. Intelligence—”Sabi Guy”. | Branding. Performance. Sexual labels and marketability—Top, Hung, Masc. |

| Time Perception | Relational time. Talking and “wasting time” together builds trust. | Industrial time. Time must yield a product—orgasm. Anything else is inefficiency. |

| The “Block” Button | Used primarily for safety. Avoiding threats and exposure. | Used primarily for disposal. Deleting a failed transaction. |

10. Rebuilding Trust and Intimacy in UK Queer Spaces

Rebuilding intimacy in the UK doesn’t require romanticising Nigeria’s dangers. It requires a deliberate shift in values: if Nigeria taught community care under pressure, the task here is to practise care without pressure. Done well, this can produce something close to a utopian social atmosphere.

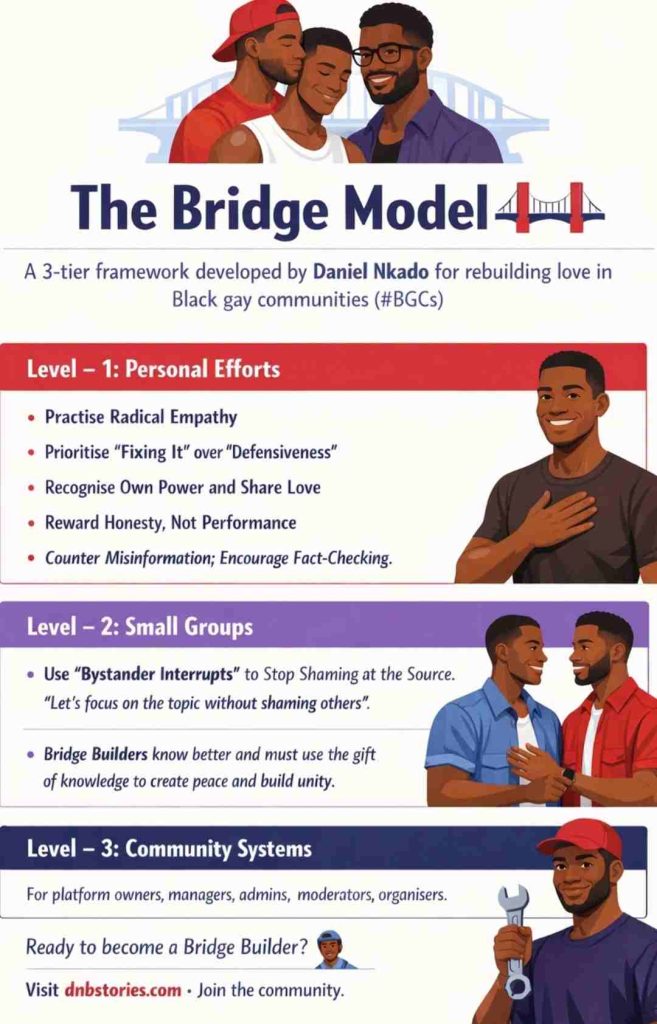

a. The Bridge Model: Repairing Wounds & Rebuilding Trust in UK Queer Spaces

The first step in restoring the value of genuine human connection is to heal community wounds and rebuild trust. The Bridge Model offers a three‑level framework—Individual, Small Group, and Community—that maps concrete, actionable steps for repair. If each of us adopts the role of Bridge Builder, we move from passive hope to deliberate practice, actively creating the change we want.

Practical individual actions from The Bridge Model you can start today:

The Bridge Model begins with personal effort.

Here are clear, repeatable practices that, together, we can use to move queer culture from performance to care. Start by choosing one or two to apply this week—small, consistent actions build into new norms.

| Practice | Why | Script / Action |

|---|---|---|

| Practise Radical Empathy | Affirms relationship while holding boundaries. | “I love you, and I need to say this landed on me as hurtful.” |

| Prioritise Fixing It over Defensiveness | Repair restores trust faster than justification. | “I didn’t realise I hurt you. I’m sorry—how can I make this right?” |

| Recognise Your Power | Power can protect or punish; choose to redistribute care. | Amplify quieter voices; offer resources or introductions. |

| Reward Honesty, Not Performance | Social incentives shape behaviour; reward authenticity. | “Thanks for being real with me—that matters more than looking perfect.” |

| Counter Misinformation | Accurate information prevents harm and reduces gossip‑based shaming. | “Let’s check that before we share it—can we confirm first?” |

| Use Bystander Interrupts to Stop Shaming | Immediate interruption signals that shaming is unacceptable. | “That landed as shaming. Can we not use language like that here?” |

| Practise Flexibility During Meet‑Ups | Elasticity preserves social capital and creates durable networks. | Offer a transition: “If the sexual part fades, I’d like to keep you in my life as a friend.” |

10. Conclusion: Rebuilding Love in the West

Safety is a human right; connection is a human need. But safety alone does not create intimacy—it merely clears the space in which we can intentionally build it. Reestablishing community means moving beyond protection to active practices that cultivate trust and belonging. Safety opens the door; what we choose to build inside it determines whether real intimacy follows.

Don’t Navigate This Alone.

Migration changes everything—including how we love and connect. If you are navigating the complexities of queer life in the diaspora, you don’t have to do it in isolation.

Join the DNB Community on Telegram or subscribe to our newsletter today to join a community of thinkers and Bridge Builders working to restore intimacy in a disconnected world. Receive exclusive research‑led essays, community stories, and practical resources delivered straight to your inbox.

References

- Amnesty International. (2014, January 15). Nigeria: Halt homophobic witch-hunt under oppressive new law. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2014/01/nigeria-halt-homophobic-witch-hunt-under-oppressive-new-law/

- Drury, J., Carter, H., Cocking, C., Ntontis, E., Tekin Guven, S., & Amlôt, R. (2019). Facilitating collective psychosocial resilience in the public in emergencies: Twelve recommendations based on the social identity approach. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(141). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00141

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. FGN. (2013). Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act, 2013. Official Gazette.

- Human Dignity Trust. (2024). Nigeria: Country profile. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/country-profile/nigeria/

- Human Rights Watch. HRW. (2016, October 20). “Tell Me Where I Can Be Safe”: The impact of Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/20/tell-me-where-i-can-be-safe/impact-nigerias-same-sex-marriage-prohibition-act

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Pronk, T. M., & Denissen, J. J. A. (2019). A Rejection Mind-Set: Choice Overload in Online Dating. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(3), 194855061986618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619866189

- Stonewall. (2018). LGBT in Britain: Health Report. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/lgbt_in_britain_health.pdf

- Woerner, J., Chadwick, S. B., Nadav Antebi-Gruszka, Siegel, K., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2023). Negative Sexual Experiences Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men Using GPS-Enabled Hook-Up Apps and Websites. Journal of Sex Research, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2269930