Intro: How Shame Drives Compulsive Sex In Black Gay Men

Many Black gay men learn early to hide their desire and swallow the pain of being constantly policed, humiliated, and marked as different in silence. Over time, this builds a tall pillar of shame that follows us everywhere, making us police ourselves—and sometimes each other—even more rigorously than the world does. When sex becomes the quickest way to feel wanted or soothed, we run to it in every moment of distress.

The relief is real but brief. The rush fades, the shame pillar returns—now wider with self‑judgement. The pattern feels foreign, out of step with who we believe we are. We frame it as personal failure, but that only feeds the cycle. With limited understanding, we treat the behaviour as the problem and overlook its cause. Like outdated software, the brain keeps reaching for the only solution it knows.

This isn’t another article telling you to want less or do better. It is an exploration of how visibility—being seen, named, and held without correction, shame, or judgment—can disrupt the cycle of compulsive sexual encounters in Black gay men, turning secrecy into connection and urgency into choice.

- Intro: How Shame Drives Compulsive Sex In Black Gay Men

- 1. How Silence, Secrecy & Invisibility Build Shame in Black Gay Men

- 2. How Shame Turns Sex Into Compulsive Coping

- 3. Black Gay Men and the Science of the "Void"

- 4. What Is Visibility And Why Do Black Gay Men Fear It?

- a. Queer Visibility

- b. Social Visibility vs. Sexual Visibility in Black Gay Men

- Black Gay Men: Hypervisibility vs. Invisibility

- Why True Visibility Feels Risky For Black Gay Men

- A. African-Context Barriers to Queer Social Visibility

- B: The Western Context—USA/Canada/UK/Europe

- Visibility and Black Gay Masculinity

- 5. Visibility as the Antidote: Healing Compulsive Sex

- 6. When Full Outness Isn’t Safe

- Role Of Underground Queer Communities

- Dynamic Disclosure: Harm Reduction Through Strategic Visibility

- Digital Visibility Helps, But It Has Limits

- Challenging Femmephobia and Visibility Shaming in Black Gay Men

- Harm Reduction for Sexual Behaviour

- How Black Gay Elders Can Help

- Key Takeaways

- Call To Action: Start Small

- References

A Quick Note on Language:

This article offers education, not diagnosis. I use “compulsive sex” descriptively—to name repeated sexual behaviour that can feel driven, numbing, and hard to stop, especially when used to escape shame or emotional pain among Black gay men—not as a formal psychiatric diagnosis. It offers community-based reflection and harm reduction, not therapy, medical advice, or clinical care.

1. How Silence, Secrecy & Invisibility Build Shame in Black Gay Men

The cycle described above doesn’t start with sex. Chasing sex reflects the outcome, not the root cause. It often begins with invisibility—hiding what we’ve learned not to name, not to ask for, and never to reveal. Over time, all the hiding and secrecy train the brain to associate who we are and what we desire with danger, inviting fear.

But fear usually signals a specific threat. This feels different because it appears everywhere—at school, at home, on the bus, in the store, even in moments of excitement or celebration. We feel it, like a shadow around us. It isn’t tied to one dangerous place. It’s tied to us.

a. Early Shaming and the Birth of Silence

Often, the first shaming moment doesn’t explain the threat. Someone snaps, “Don’t move your hand like that—boys don’t do that.” But they don’t tell you why, what will happen if boys do, or who exactly you’re being protected from. The warning arrives without context, leaving the story incomplete.

Even the bully delivering the warning—often just another confused kid—doesn’t fully understand the threat. He’s only repeating what he picked up. But the tone carries the real message: this isn’t up for debate. It’s not just “don’t do that”—it’s don’t ask, don’t name it, don’t bring it to school.

And when a child can’t name what’s happening—stigma, policing, gender enforcement—the brain reaches for the simplest explanation available:

Maybe the problem is me.

This lays the foundation of shame in many Black gay men—silence.

b. Silence → Secrecy → Shame: How the Pillar of Shame Forms

As the innocent kid gets older and begins to feel drawn to boys, dread sets in. This is it. Now it “makes sense.” The brain treats those early warnings as confirmed: I knew something about me was dangerous.

What could have been met early—with kind-hearted explanation, reassurance, and plenty of hugs—gets missed. Not because the child is unlovable, but because the adults they most need may not feel informed or equipped enough to help. When Mum and Dad can’t be trusted to make things better, the child’s nervous system does what it was designed to do: it builds its own protection.

That’s how the over-zealous Judge Saboteur gathers his friends and gets to work—constructing, day and night, from every confusion the boy feels, every moment of isolation, each distance, each exclusion, every insult and sneer. Every time his body was used without any acknowledgement of his person. Over time, a pillar of shame is erected. It quickly becomes an internal guard that follows you everywhere, repeating one instruction on a loop: don’t let them see that part of you.

The mind genuinely believes it’s doing the right thing. The brain is built on a survival‑first logic, using whatever information it has to keep you safe. And most of these patterns take shape during adolescence—periods of high neuroplasticity, when the brain is rapidly learning what the world is and what you must do to belong in it.

That’s why a clear explanation could have changed everything. Not a lecture—just a simple truth: You’re not bad. You’re not alone. Nothing is wrong with you.

The Three Steps of Shame Formation in Black Gay Men Summarised:

Stage 1: Silence—Often starts as self-protection. You learn quickly that certain truths invite ridicule, punishment, or withdrawal of love, so you stop naming them. At this stage, you’re not necessarily lying—you’re withholding.

Stage 2: Secrecy—As the boy grows older, silence becomes an active form of management. Now you’re not just quiet—you’re building systems to prevent exposure: editing stories, controlling body language, splitting your life into compartments, monitoring who knows what, and some might even start policing others—not out of genuine malice but as a residual effect of the internal turmoil we deal with. This stage is high-pressure—the nervous system understands that the danger we represent is significant.

Stage 3: The Pillar of Shame—Secrecy does not just hide the truth, it wrongly confirms to the brain that “something is indeed wrong with me.” This is the banner spread atop the pillar—a constant reminder never to forget. The brain just wants to stay alive—but only by what it knows. Once that meaning solidifies, shame becomes structural—like an internal guard you carry everywhere, constantly scanning and correcting you.

2. How Shame Turns Sex Into Compulsive Coping

When you internalise “something is wrong with me,” it doesn’t land like a neutral observation—like a disability label or a simple limitation. It becomes a template that keeps emitting messages:

- You are worthless.

- You are contaminated.

- Fine boy, but still an abomination.

- Intelligent, but still not a real boy.

- Weirdo.

- You can try to be a good boy all you want, but you are still going to HELL!

Shame doesn’t clarify meaning; it just marks you as the problem. It locks you into a cage where your nervous system stays guarded, constantly scanning for threats and collecting each new insult, rejection, or shaming moment as further “evidence.” Over time, the mind builds a vocabulary of fault: more reasons why I must stay hidden, controlled, edited.

This relates to what psychologists describe as minority stress—the chronic strain that comes from being repeatedly stigmatised, policed, or made unsafe, and from having to anticipate those harms even when they aren’t happening in the moment[6].

The Void Gay Men Feel—What Is It Really?

Because the “fault” implied isn’t visible or physical, the brain tries to represent it differently: as an inner absence—a hollow space where worth should live. This is where the shame pillar takes up residence, constantly reminding you of your supposed inadequacy.

The void doesn’t look the same for everyone. For some, it’s a vast emptiness; for others, a gradual erosion of self‑worth. In every case, it generates deep emotional distress.

When we encounter distress that hits deep—a homophobic attack, sharp rejection, an identity‑level humiliation—the pillar doesn’t feel like it’s “there” anymore. What you feel instead is what sits beneath it: the void, loud and jarring.

In that moment, the brain marks anything that brings relief as urgent and medicinal—sex, substances, validation, attention—even if the effect lasts only minutes. That’s reinforcement: the brain learns, when I feel this, do that. Once relief becomes a learned response, the pull becomes compulsive.

Sex as a Coping Mechanism: Short-Lived Relief

The relief from sex fades fast, and when it does, the crash can feel worse: now you’re not only carrying the original shame—you’re also carrying additional regret and self-judgment about how you coped. The void can feel wider afterwards, which creates pressure for a stronger internal guard—a taller shame pillar—and a higher “dose” of whatever worked last time. That’s how shame turns sex from pleasure into compulsive coping.

This same dynamic can also help explain why compulsion often escalates over time. As the brain builds tolerance to brief relief, it starts seeking a stronger or more frequent “dose”—more intensity, more novelty, more risk, or simply more encounters—to achieve the same numbing effect.

The Chaos of Shame-for-Being

In this sense, shame enters a space it was never meant to occupy. In ordinary shame, you at least know what you did—your inner saboteur is punishing you for a choice the brain believes was dangerous. That’s the brain’s crude way of preventing repeat “bad” behaviour. But shame‑for‑being is different. It doesn’t just wound; it creates internal chaos. It fractures identity, heightens self‑vigilance, and drives people toward compulsive coping—sex, substances, anything that briefly makes them feel whole in a world that keeps treating them like an outcast.

Why Shaming Others Deepens Our Own Internal Shame

Shaming others often reflects an unconscious act of projection—offloading unwanted or painful parts of the self onto someone else. But when you shame others, you don’t just police them; you train your own inner critic. Every time you judge someone for being “too gay,” “too femme,” a “greedy bottom,” or “having a small one,” you reinforce the same hostility your inner voice later turns on you. Shaming others confirms the truth of our own internal shame. This strengthens the inner pillar of shame, resulting in a harsher internal environment that produces greater self-surveillance, greater tension, and greater urgency for escape[1].

3. Black Gay Men and the Science of the “Void”

Being human entails regularly encountering emotional distress. But when loneliness, fear, and unmet needs stay hidden—when we don’t name or share what we feel—they quietly form new layers around the pillar of shame many of us have carried since childhood. Instead of losing power, that shame grows. The more everyday distress we absorb in silence, the more urgently we crave relief.

This is the engine behind the compulsion cycle I’ve described before: how past and present shame consolidate into an internalised sense of worthlessness—the shame void. A trigger‑sensitive hollowness in the mind that holds our deepest fear: being nothing, having no value. Once it forms, it doesn’t take much to activate. And when it’s triggered, the discomfort doesn’t register as emotion but as a threat. The brain senses danger. In that moment, the survival brain overrides the thinking brain and drives us toward the fastest relief it knows or remembers—sex.

a. Why Our Brain Interprets Shame As Threat

The brain reads shame-for-being as a threat because, evolutionarily, shame signalled social exile—and social exile once meant death. Humans survived through belonging, so shame evolved as an alarm system designed to prevent rejection. As a result, the brain often treats social danger like physical danger. Our minds don’t neatly separate “I’m unsafe” from “I’m unwanted.” Rejection, humiliation, and worthlessness can activate the same pain pathways as bodily injury, so when shame unearths messages that signal “you don’t matter,” the nervous system responds as if survival is on the line.

b. The Sex‑For‑Coping Chase

The sex‑for‑coping chase describes a compulsive pull toward sexual encounters driven less by desire or connection and more by the need to regulate distress—to numb pain, escape discomfort, or briefly feel worthy. In this pattern, sex becomes a fast relief. It quiets shame and anxiety for a moment, but leaves the underlying void unchanged.

The relief from sex is real but brief. It alleviates discomfort in the moment, calms the nervous system, and allows us to return to work. But it leaves the pillar of shame untouched—so the void soon returns, and the cycle resets.

c. Black Gay Men And The Human Need To Feel Seen & Desired

Every human being has an underlying need to feel loved, accepted, safe, and worthy as they are—without having to wear a mask, perform hypermasculinity, or live in secrecy. When that need goes unmet, some people turn to sex to bridge the gap. The logic here is simple: sex feels like one of the few accessible spaces where masks drop, performances soften, and desirability becomes immediate. But that’s sex doing more emotional labour than it’s built to carry.

During sexual activity, the brain releases dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in reward and motivation. The surge creates feelings of relief and satisfaction, briefly quieting distress and sharpening focus on the present moment. For a brief period, the nervous system stabilises, the body calms, and the person can return to everyday life.

When the high fades, the thinking brain returns—bringing back values, ambitions, responsibilities, and the realities still waiting. With unresolved shame still intact, the return feels harsh—the nervous system shifts from numbness back to active threat.

That’s often why the cycle keeps tightening and demanding higher doses of relief. You’re no longer soothing only shame; you’re also trying to soothe its offspring—self‑judgment. And because sex worked quickly before, the mind reaches for it again, not out of desire, but out of a learned pattern for relief.

What The “Sex-For-Coping” Chase Looks Like

The chase is defined by its function, not just by the frequency of sex. For a Black gay man navigating high-stress environments, the pattern often looks like this:

a. Relief Over Enjoyment: The primary feeling after sex is “I needed that to calm down,” rather than “that was fun.”

b. The High/Crash Cycle: A spike of validation during the encounter, followed by a crash of emptiness or shame immediately after.

c. Autopilot Cruising: Opening apps—Grindr, Jack’d, Sniffies—automatically the moment you feel stressed, lonely, or rejected by family or work.

d. Status Seeking: Specifically seeking partners who symbolise status—hyper-masculinity, proximity to whiteness, or financial power—to repair a bruised ego.

4. What Is Visibility And Why Do Black Gay Men Fear It?

a. Queer Visibility

Queer visibility—more specifically, queer social visibility—is the public recognition of queer people, lives, identities, and stories, so they aren’t hidden, erased, or presumed straight or cisgender.

True visibility means queer people are seen, named, and acknowledged across everyday life—media, workplaces, schools, public life, healthcare, law, and politics.

Queer liberation frameworks often treat visibility as essential to advancing LGBT rights.

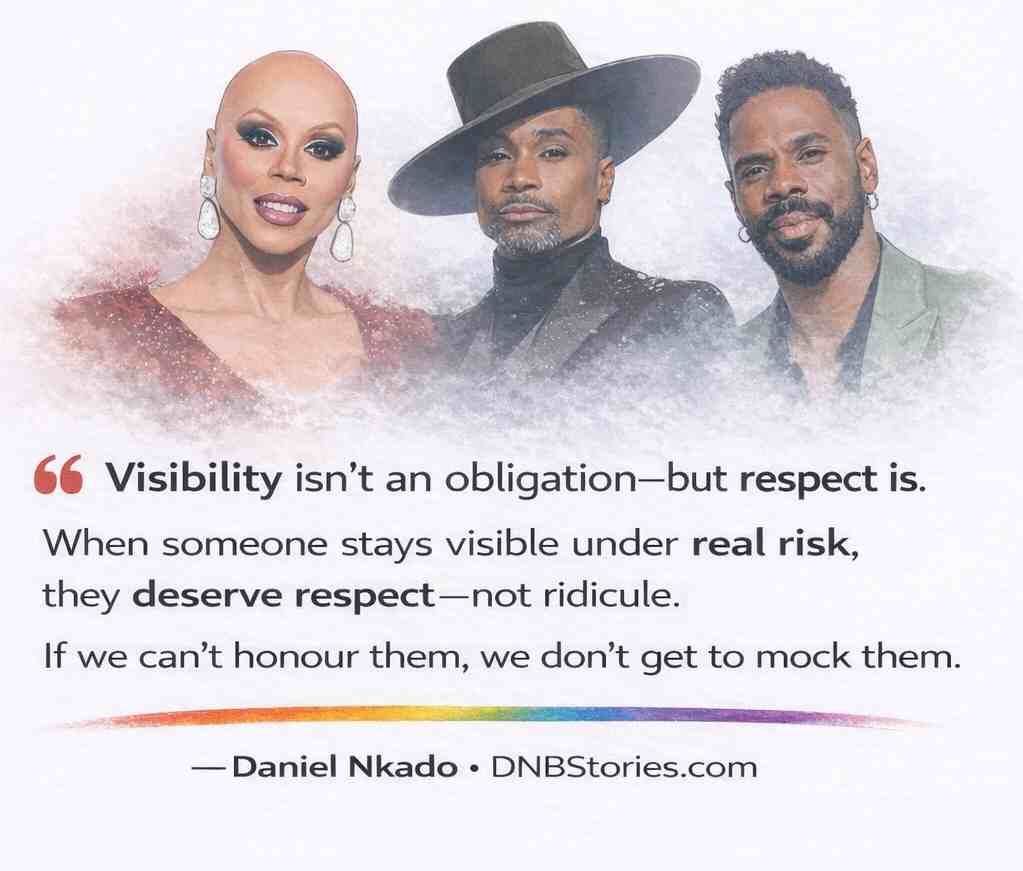

However, Queer Visibility must be approached with care and full understanding, as it operates differently across contexts. What feels liberating in one setting may prove dangerous or destabilising in another. Visibility, therefore, is not a moral obligation but a negotiated practice shaped by culture, power, and survival.

b. Social Visibility vs. Sexual Visibility in Black Gay Men

Social visibility is the experience of being known and recognised as a full queer person in everyday life—without having to hide, self‑edit, or reduce yourself to stay safe.

Sexual visibility, on the other hand, describes being seen through desire rather than a relationship. Here, the queer man is wanted and immediately chosen without having to be fully known. This type of visibility often feels easier for some Black gay men, because it’s time‑limited, demands less vulnerability, and offers immediate feedback: you’re desired.

The problem is that visibility through sex, while real, is brief. As it fades, shame returns, invisibility deepens, and sex becomes the quickest doorway back to temporary worth.

| Type of visibility | Definition | Key risks |

|---|---|---|

| Offline visibility | Being openly LGBTQ+ in physical spaces (home, work, school, public). | Discrimination, harassment or violence; family or community rejection; limited local support networks. |

| Online visibility | Expressing LGBTQ+ identity on internet platforms (social media, forums, apps). | Harassment and trolling; algorithmic suppression; pressure to conform to platform norms. |

| Digital visibility | Broader representation across digital technologies (online presence, virtual events, etc.). | Invisibility due to biased algorithms, misrepresentation or tokenism, data privacy and surveillance concerns. |

Black Gay Men: Hypervisibility vs. Invisibility

a. Invisibility

This means being unseen, unacknowledged, or erased as a whole person. Here, the person’s queer identity stays ignored or silenced, forcing them to self‑edit and hide parts of themselves to avoid consequences. While invisibility can protect against immediate danger in hostile environments, prolonged invisibility leads to loneliness, unmet needs, and deeper internalised shame.

b. Hypervisibility

Hypervisibility refers to the constant, immediate attention Black gay men often receive upon entering some spaces. It may look like affirmation, but it mostly operates through stereotypes, racial projection, or surveillance. You’re noticed quickly, but not as a whole person—people scan you for signals or assign a script: sex role, “BBC,” dominance, fetish, symbol, or threat. Because this visibility denies dignity, complexity, and safety, it often increases risk and triggers distress rather than offering protection.

Why True Visibility Feels Risky For Black Gay Men

For Black gay men, social invisibility—or “living in the closet”—often functions as a rational survival strategy shaped by real consequences. The logic of invisibility remains coherent across contexts, even when the specific risks differ.

This section examines the social and cultural barriers to visibility for Black gay men, contrasting Africa’s legal and safety‑based risks with the West’s intersectional pressures—particularly racism and homophobia both within and beyond queer spaces[7].

A. African-Context Barriers to Queer Social Visibility

In many African contexts, queer visibility can threaten legality, lineage, belonging, and survival—so silence becomes a rational shield, not a sign of confusion.

i. The “Un-African” Narrative

In many African countries, public discourse falsely frames homosexuality as a Western import or colonial corruption. This framing turns visibility into a heritage dispute—shifting outness from a personal identity issue to cultural betrayal—of “Africanness,” family tradition, and ancestors.

ii. Manhood As Procreation

In contexts where masculinity is tightly bound to fatherhood, “being a man” often takes on a single, direct meaning—producing heirs and extending the family line. When a man becomes visible as gay, his kin may read it as refusing that duty, even as “ending the lineage,” layering his personal shame with the weight of public obligation.

iii. Legal and Physical Safety

In places where same‑sex intimacy remains criminalised—or where societal stigma reaches dangerous levels—visibility becomes a legal and safety risk, not merely a social choice. In countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, and Uganda, even digital visibility can carry serious consequences: a dating profile, a private chat, or a social media trail can expose someone to harassment, arrest, or exploitation. Reports consistently document patterns of “Kito” entrapment, extortion, and blackmail targeting LGBTQ people through dating apps and online platforms.

iv. Communal shame and Ubuntu logic

Ubuntu—“I am because we are”—binds identity to the collective. At its best, it protects belonging and mutual care. At its worst, families weaponise it, treating one person’s queerness as a stain that spreads—bringing shame, dishonour, or “misfortune” onto parents, siblings, lineage, and community standing. Within this logic, visibility becomes the fear of being cast as the one who “spoils” the peace.

v. Religious dominance as social infrastructure

Where churches and mosques function as major community institutions—providing moral authority, social standing, and practical support—visibility can trigger more than spiritual condemnation. It can mean social exile: losing networks that often carry real resources and protection, especially in places where state support is limited.

B: The Western Context—USA/Canada/UK/Europe

i. Family Expectations and Cultural Pressure

Strong family expectations can make many Black gay men hesitant to live openly. In many Black families—including African and Afro-Caribbean diaspora communities—parents and elders often expect sons to “be a man,” marry a woman, and continue the family line. When relatives frame queerness as incompatible with those roles, visibility can feel like choosing personal truth at the cost of family belonging.

ii. Masculinity Pressures

In Western contexts, Black gay men often use masculinity as armour—projecting strength to shield against stigma and to feel more desirable in a racialised world. Because social visibility often demands openness and some degree of queer readability, many feel compelled to choose between visibility and protection.

iii. Separation from Mainstream Queer Spaces

Many Black gay men experience a clear divide from the mainstream “gay community,” often because of racism, fetishisation, and exclusion that permeate some of these spaces. Queer culture often centres whiteness, leading some Black men to view visibility as “a white gay thing.”

iv. Community Pressure

Some Black communities frame queerness as a liability—another reason white society might use to judge Black people. That framing turns visibility into a communal risk, not a personal right. To avoid stigma, conflict, or blame, some Black gay men choose discretion even in relatively safer environments[3].

v. Desirability and the “Down Low” Mask

In some segments of Western Black gay communities, persona performance on dating apps has increasingly become a route to status and desirability. This often involves strategic signalling of “hood” or DL archetypes, rigid sexual positioning, and sustained straight‑passing labour. When desire hinges on performing a caricature of hyper‑masculinity or proximity to straightness, visibility loses its meaning. You get loads of attention, but people only see the role, persona or aesthetic you represent, not the real you—and they do not really care to[5].

Visibility and Black Gay Masculinity

In many Black cultural contexts, people equate being a “real man” with being straight, physically tough, and emotionally guarded. When a Black man lives openly as gay—or simply expresses softness[2]—peers may ridicule him, question his manhood, or accuse him of betraying Black masculinity. Every-day slurs, jokes, and put‑downs aimed at “soft” or femme men reinforce these norms and create a chilling effect: many learn to self‑edit, stay discreet, or avoid visibility altogether to protect their social standing and emotional safety.

5. Visibility as the Antidote: Healing Compulsive Sex

Every person has core emotional needs—love, safety, validation, and care—simply for existing. When these needs stay neglected (especially in childhood or adolescence), people often carry it into adulthood as low self-worth, anxiety or depression, and unstable relationship patterns—swinging between extreme independence and codependency. For Black gay men, compulsive sex can become one way to self-soothe unmet needs and manage deep shame.

In this context, true visibility acts as a powerful healing agent. When our inner lives—our loneliness, fear, softness, and desire—receive acknowledgement without “correction” or judgement, sex no longer has to carry the entire emotional load. Compulsion begins to loosen—not because of discipline or self‑mastery, but because the weight of life is no longer being carried alone[4].

Authentic Black Queer Visibility is the ability to say, “This is what I reach for when I’m hurting,” and be met with understanding—not policing. It’s the freedom to catwalk in high heels and get applause instead of sneers. It’s being able to say, “I tried bottoming last night and made a mess,” and have people laugh with you—not at you—because you started laughing first.

What Black Queer Visibility Is and What It Is Not

For Black gay men, queer visibility is more than being seen—it’s about being understood, respected, and represented as whole people. It means living openly at the intersection of Blackness and queerness without having to hide, fragment, or “pick a side.”

To understand the importance of visibility, we must first distinguish authentic representation from harmful distortions.

What Black Queer Visibility Is Not

True visibility does not reinforce old prejudices; it dismantles them. To understand what meaningful representation looks like, it’s important to reject the following misconceptions:

It is not Hypersexualisation

Visibility should never reduce Black men to spectacles of sexuality. For centuries, racist tropes—like the BBC and “Mandingo” myth—and media stereotypes have portrayed Black men as hypersexual, dangerous, or animalistic. Genuine visibility rejects these one‑dimensional roles and insists that Black gay men are also romantic, vulnerable, intellectual, soft-skinned, creative, and relational.

It is not Tokenism

A single Black gay character in a show or one person on a corporate board is not representation—it’s box‑ticking. Tokenism offers a shallow presence often built on cliché—the “sassy gay friend,” the comic relief, the sidekick with no interiority. True visibility requires depth, range, and multiplicity: not one story, but many.

It is not a “Betrayal” of Black Culture

The idea that being openly queer is “not a Black thing” or a betrayal of cultural or religious values is simply false. Black gay men have always been central to Black history, culture, and activism—figures like Bayard Rustin are proof. Visibility challenges the “down low” stigma and affirms that one can be fully Black and fully queer without contradiction.

What Authentic Black Queer Visibility Is

When stripped of stereotypes, visibility becomes a tool for empowerment and mental well‑being.

It Must Be Chosen

Choice is the foundation of authentic Black queer visibility. Real visibility is never imposed; it must come from personal readiness, safety, and self‑determination—not pressure from the community, the media, or partners. When visibility is chosen, it empowers. When it’s forced, it creates harm.

It is Intersectional

Authentic visibility allows Black gay men to live wholly and freely in both identities. It affirms that their experiences matter and that they belong fully in both the Black community and the LGBTQ+ community—without having to hide, split, or choose between them.

It is Community‑Rooted

Real visibility often begins in safe, affirming spaces—ballroom culture, support groups, chosen family, and households that nurture rather than police. These environments counteract isolation and shame, replacing them with connection, affirmation, and belonging.

It is Nuanced Representation

Whether through media like Moonlight, Pose, and Noah’s Arc, or through public figures such as Frank Ocean and Darnell Moore, authentic visibility presents Black gay men as complex individuals with interior lives, relationships, careers, families, and futures. It moves beyond caricature and restores depth, humanity, and range.

6. When Full Outness Isn’t Safe

For many Black gay men—especially those navigating religious families, hostile workplaces, or regions with harsh anti‑LGBTQ+ laws and high stigma—full public visibility can be genuinely unsafe. In these contexts, healing can still happen through strategic visibility.

Role Of Underground Queer Communities

Underground queer networks make Black queer visibility possible even in hostile environments, offering discreet, trust‑driven channels for connection and care. These networks often form naturally through friendship circles, creating spaces that allow LGBTQ+ people to feel “seen” in safe, discreet communities without becoming visible to hostile institutions.

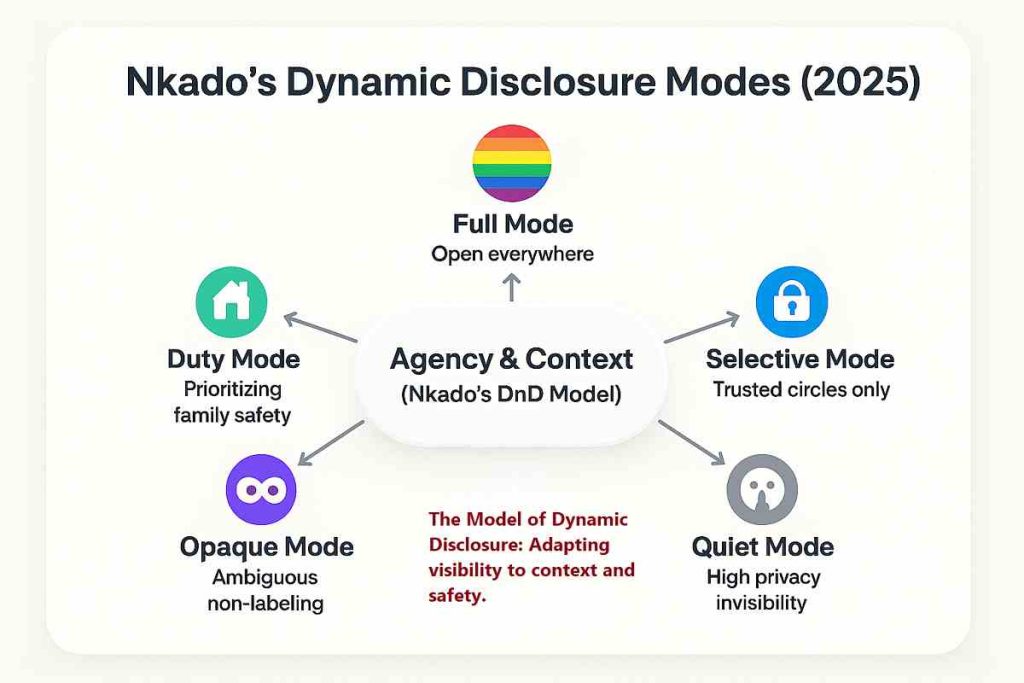

Dynamic Disclosure: Harm Reduction Through Strategic Visibility

Daniel Nkado’s Dynamic Disclosure Model treats disclosure as a continuous, situational choice—not a simple “in” or “out.” It supports real‑time risk assessment: withhold visibility in unsafe settings, and practice vulnerability in safer ones—chosen family, trusted friends, support groups. The goal shifts from “being out everywhere” to “being open where it matters,” protecting safety while maintaining inner authenticity. The mind knows clearly that hiding is for protection, not shame.

Digital Visibility Helps, But It Has Limits

Online spaces can offer digital visibility—a lower-risk way for Black gay men to explore identity, find language, and feel seen. But when online freedom meets offline restriction, it can become a digital closet, widening the gap between who you are online and who you must be offline—and raising stress. The goal isn’t to leave the internet, but to build bridges toward trusted, real-world connections where possible.

In the Model of Dynamic Disclosure (MDD), this comes in Selective Mode: you choose the audience, pace, and boundaries—using visibility as support without sacrificing safety.

Challenging Femmephobia and Visibility Shaming in Black Gay Men

Research shows that Black gay men often diverge in their responses to masculinity policing and homophobia: most adapt by adhering to traditional masculine norms, while others subtly challenge them while remaining acutely aware of the boundaries. Very few push those limits—such as wearing makeup or coming out publicly—knowing it can bring real social sanctions. The community should protect this group rather than reject them.

Harm Reduction for Sexual Behaviour

If stopping the behaviour feels impossible right now, focus on safety and agency while you work on healing:

i. The H.A.L.T. Check: Before opening an app, pause and ask: Am I Hungry, Angry, Lonely, or Tired? If yes, address that need first.

ii. Boundaries: Set simple, protective limits—like “No apps after 11 PM” or “No hookups when I’m feeling low.”

iii. Post‑Sex Care: Instead of spiralling into shame after a sexual encounter, practise care: shower, eat, hydrate, rest, and speak to yourself with kindness.

How Black Gay Elders Can Help

Mentorship can reduce the sex-for-coping chase by offering consistent, non‑sexual validation, co‑regulation, and a future‑facing model of Black gay life—needs that compulsive sex often tries to meet in a hurry. A reliable elder figure can help identify triggers, reduce shame, and develop safer alternatives for connection before the urge escalates.

But in many Western gay scenes, “elder” status doesn’t automatically mean stability. Some older Black gay men get caught in the same chase sometimes. That’s why the real criterion isn’t age; it’s capacity. Choose mentors with clear boundaries, emotional maturity, and a demonstrated commitment to care not tied to sex.

Key Takeaways

- Visibility is understanding, not just sight: It means to be recognised as a whole, multi‑dimensional human being, as you are.

- Visibility is an antidote to shame: Sharing the weight of our inner lives with safe people reduces isolation—the very condition that often fuels compulsive behaviours.

- Visibility matters, but safety comes first: You don’t owe the world your whole story. Through Dynamic Disclosure, you can choose when and where to be visible—so healing never comes at the cost of your safety.

References

- Barnes, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2013). Religious affiliation, internalised homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x

- Bowleg, L., Teti, M., Massie, J. S., Patel, A., Malebranche, D. J., & Tschann, J. M. (2011). “What does it take to be a man? What is a real man?”: ideologies of masculinity and HIV sexual risk among Black heterosexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13(5), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.556201

- Johnson, E. P. (2008). Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South. Univ of North Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462937.2012.691319

- Keefe, J. R., Rodriguez-Seijas, C., Jackson, S. D., Bränström, R., Harkness, A., Safren, S. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2023). Moderators of LGBQ-affirmative cognitive behavioural therapy: ESTEEM is especially effective among Black and Latino sexual minority men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 91(3), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000799

- McCune, J. Q. (2014). Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing. The University Of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo17092702.html

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Sarno, E. L., Swann, G., Newcomb, M. E., & Whitton, S. W. (2021). Intersectional minority stress and identity conflict among sexual and gender minority people of colour assigned female at birth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000412

- Snorton, C. R. (2014). Nobody is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.indigo.ca/en-ca/nobody-is-supposed-to-know-black-sexuality-on-the-down-low/

- Wade, R. M., Bouris, A. M., Neilands, T. B., & Harper, G. W. (2021). Racialised Sexual Discrimination (RSD) and Psychological Wellbeing among Young Sexual Minority Black Men (YSMBM) Who Seek Intimate Partners Online. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00676-6