Black gay spaces—on dating apps, in nightlife, in friendship circles, and across diaspora community networks—are often imagined as places of refuge.

Yet the places we expect to be sanctuaries can reproduce chaos through quiet ranking systems that corrode trust: who gets protected, who gets mocked, who gets pursued, and who gets treated as disposable. Over time, these unofficial hierarchies turn what could have been a source of collective pride into a machine of pain.

In this article, I map eight common hierarchies in Black gay spaces and offer a practical framework for repairing community cracks and rebuilding love and trust: The Bridge Model.

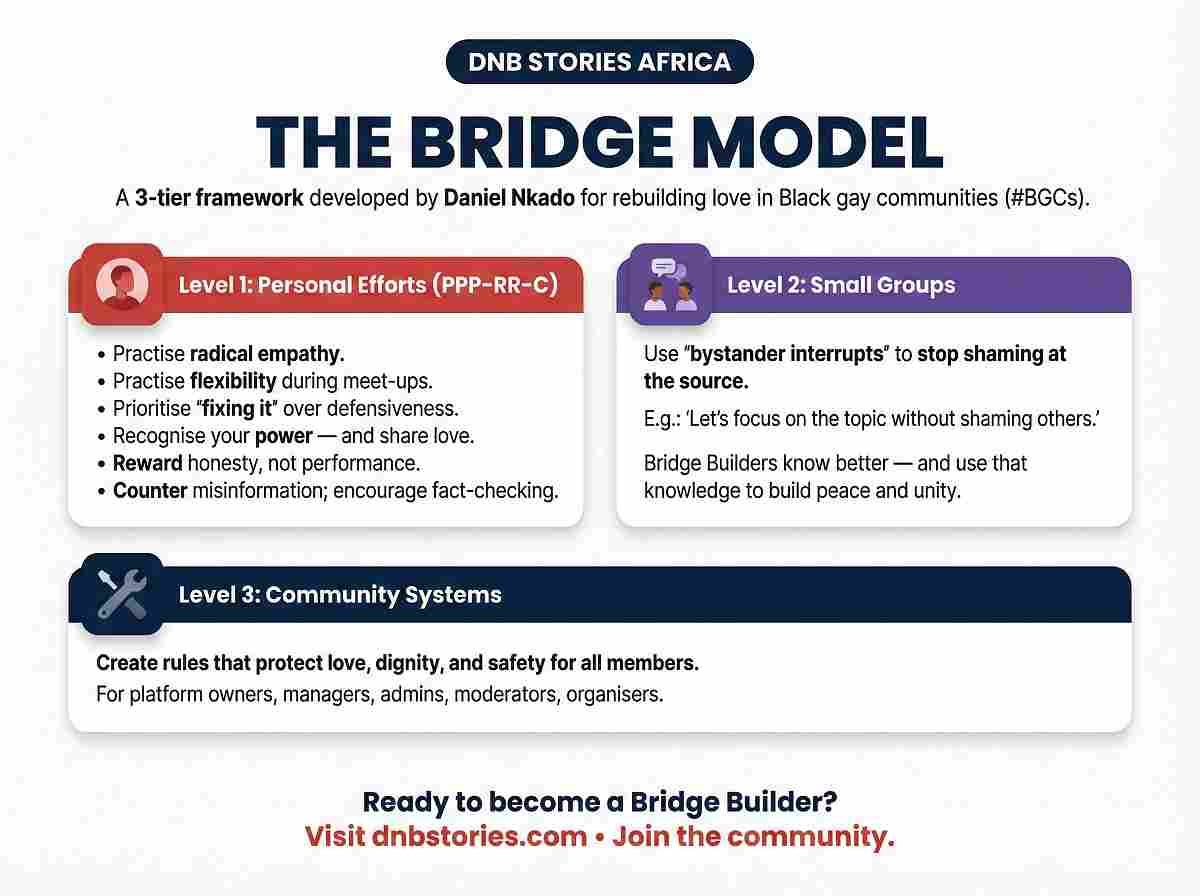

Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model is a three-tier approach that moves community culture from competition to care, and from silent harm to structured repair.

- Definitions

- Why hierarchies form in Black Gay Spaces

- How hierarchies create distrust and break communities

- 8 Common Hierarchies in Black Gay Spaces

- The Hidden Costs of Hierarchies in Black Gay Spaces

- How to Rebuild Community Love Using Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model

- How to Use the Bridge Model in Real Life

- Conclusion

- References

Definitions

- Black gay spaces (as used here): These are social environments and communities where Black gay/bi men and other Black queer men interact—online and offline. Examples include apps like Grindr and Jack’d, clubs, parties, house functions, friend groups, WhatsApp/Telegram circles, diaspora networks.

- Community love: The practical, everyday version of solidarity—dignity, mutual protection, fairness, care, and accountability—especially for people most likely to be mocked, excluded, or fetishised.

- Hierarchy: A repeated pattern where certain traits are treated as “higher value,” and others are treated as disposable or demeaning—expressed through desirability, inclusion, protection, attention, and respect.

This article explains why some Black gay spaces feel unsafe and how Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model can help communities rebuild trust.

Why hierarchies form in Black Gay Spaces

Hierarchies don’t appear from nowhere. They often form under pressure: racism, homophobia, economic precarity, immigration stress, HIV stigma, and the daily need to manage risk.

Like what happened under slavery, survival strategies formed under intense pressure can harden into status codes—even after the pressure shifts or eases:

- Masculinity as “safety”

- Straight-passing as “value”

- Thinness as “discipline”

- Whiteness as “proof”

- Wealth as “merit”

- Specific versions of Blackness as “legitimacy”.

Many ranking systems inside Black gay communities mirror the world outside. When survival is on the line, communities can start rewarding whatever seems to reduce exposure to harm.

Over time, even after the people who built these systems have passed on, younger generations continue to reproduce them—often without understanding their origins, purpose, or the codes that once governed them.

A clear example is DL signalling on dating apps[4] and Snapchat in relatively safer contexts like the UK or the US. Some men use the label as a status marker that implies exclusivity. Yet in many of its original contexts, “DL” functioned less as prestige and more as a survival practice: a discreet signal that allowed Black gay men—across class, masculinity, and identity lines—to find one another in hidden circles during a time when living openly carried real risk.

The Triple-Jeopardy Case for First-Gen Black Gay Men in the UK

Minority stress research shows how stigma, discrimination, and the pressure to conceal identity shape the mental health and social behaviour of gay men over time. For sexual minority men of colour, studies describe a “double jeopardy” of racism and homophobia—an overlapping set of stressors that not only harm wellbeing but also intensify internal tensions within the community.

For first‑generation migrants in places like the UK, an additional layer of cultural, religious and familial pressure compounds these burdens, effectively creating a “triple jeopardy” (Frost & Meyer, 2023)[3].

How hierarchies create distrust and break communities

Distrust doesn’t usually begin with one dramatic betrayal. More often, it grows from a pattern where people learn—through repetition—that vulnerability is punished and dignity is conditional.

When dignity shifts from something inherent to something you must earn, competition follows. And once competition becomes the organising principle, ranking systems emerge—structures where being “above” others matters more than being in community with them. In those environments, fairness dissolves, solidarity thins, and the collective “us” collapses into a solitary “me.”

8 Common Hierarchies in Black Gay Spaces

1. Masculinity hierarchy

- The “Masc4Masc / No Fems” bloc

- “I’m not like those dons, sass queens, woke gays” politics.

- Performing hypermasculinity to hide feminine traits and avoid stigma.

2. Sex-role hierarchy

- “Total Top” culture vs. bottom-shaming

- Bedroom preferences turned into a public ranking

3. Body hierarchy

- The “Gym bros / No fats” bloc

- Body type [7]used as social capital and “health” language used to sanitise contempt.

4. Proximity-to-straightness hierarchy

- DL posing on apps, Hood, Trade/ hyper-discreet prestige

- Using “I don’t have gay friends” as a superiority claim.

- Treating out men as “messy” or risky, especially by someone who is more “out” in practice.

- Policing who is out and not; LGBTQ visibility police.

5. Proximity-to-whiteness hierarchy

- White validation and fetishisation

- Treating white desirability as proof of value

- Treating Black-on-Black desire as “settling”

- Accepting and flaunting fetish talk (racial stereotypes, “BBC” scripts) as compliments.

6. Colour hierarchy

- Colourism and facial feature preferences

- Treating lighter-skinned men as “more refined” or dateable.

- Ignoring darker-skinned men or only hyper-sexualising/fetishising them.

7. Class hierarchy

- Bougie vs. “Ghetto/Ratchet” sorting

- Using accent, schooling, and neighbourhood as gatekeeping tools

- Shaming people for being “too loud” or “too broke.”

8. Ethnicity / National-origin hierarchy

- Intra-Black ranking in diaspora spaces

- Splits like “Yardie vs African” [8]or “Foundational vs Immigrant”

- Using stereotypes to determine desirability.

- Policing who is authentically Black or not.

These hierarchies don’t just decide who gets attention—they shape the whole community: how people speak, date, tolerate harm, and set expectations. Over time, the damage becomes normalised, inherited, and hard to name.

The Hidden Costs of Hierarchies in Black Gay Spaces

i. They normalise performance: When people are treated better only if they perform “approved” masculinity, sex role[5], class, body type, or desirability, performance becomes the price of respect.

ii. They normalise humiliation: Group bonding forms around who gets mocked—the “fem,” the “broke,” the “too African,” the “too dark,” the “too loud.” Bonding through other people’s pain keeps everyone tethered to the same pain.

iii. They reward silence: Bystanders learn that speaking up costs status, so harm becomes routine and “peace” becomes quiet complicity.

iv. They split the community: People stop relating as peers and begin relating as competitors—winners, losers, and spectators.

v. They turn intimacy into strategy: Dating becomes less about connection and more about upgrading status, avoiding shame, or managing optics[2].

vi. They manufacture rivalry: Internal ranking pits Black men against each other and normalises being valued for stereotypes rather than personhood.

vii. They can deepen poverty: When people are forced to manage reputation and exposure—burner Snaps, constant discretion, curating “acceptable” identity—they lose time, energy, and focus that could have gone to work, study, rest, and long-term stability.

viii. They harm health: Living under constant ranking pressure—hypervigilance, concealment, rejection anxiety, and chronic comparison—raises stress, fuels shame, and can worsen mental health over time.

ix. They fuel harmful behaviour: People withdraw, self-medicate, overcompensate, or stay in unsafe dynamics—just to avoid being demoted or discarded.

x. They destroy elder mentorship: Older gay men can lose sight of the duties they owe the younger generation—guidance, protection, honest counsel, and boundary-setting—leaving younger men to navigate harm alone, repeat avoidable mistakes, and mistake exploitation for care.

xi. They normalise cruelty as humour: Shade becomes a currency, and people learn to protect themselves by attacking first.

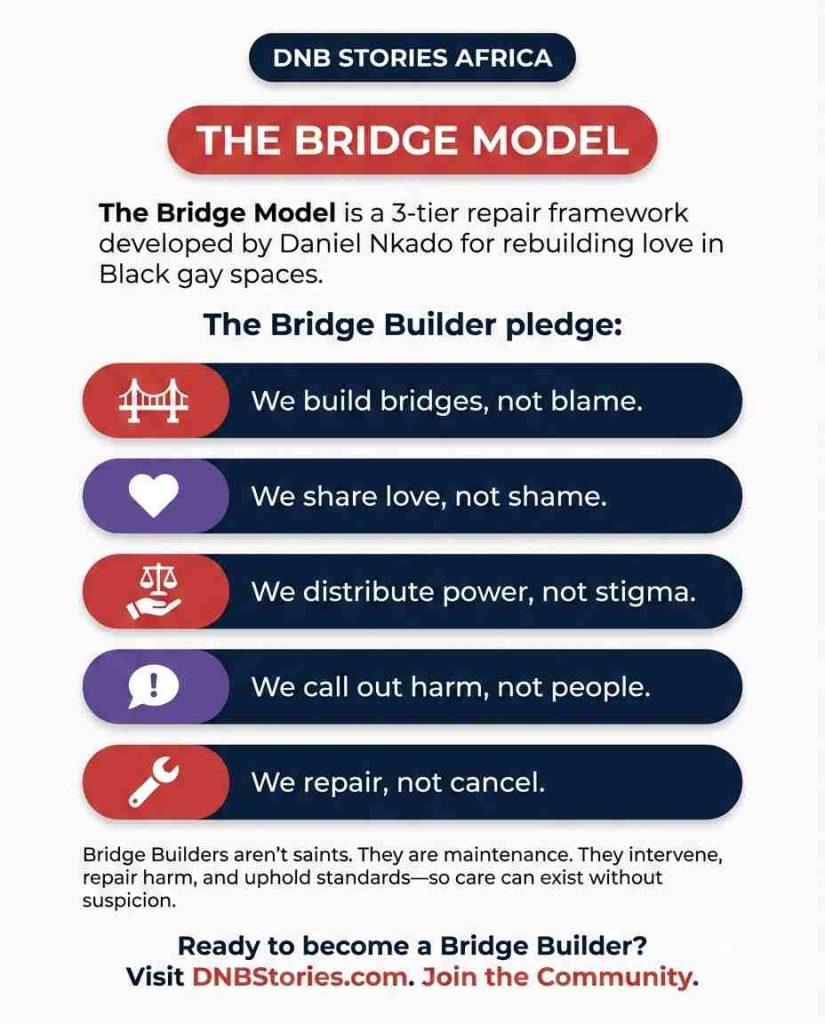

How to Rebuild Community Love Using Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model

The Bridge Model, developed by Daniel Nkado, is a three-tier framework for restoring love and repairing distrust in Black gay communities, grounded in the principle that healing is a shared responsibility.

The Bridge Model is practical because it addresses harm at the levels where it actually happens—individual actions, small‑group culture, and community rules.

It offers real-time scripts that Bridge Builders can use in everyday moments, creating quiet, consistent change in how people speak, correct, and repair harm. It scales from one person to whole networks, turning empathy into action and making community safety genuinely durable. And because many Black gay spaces blame individuals for behaviours the communities actively reward, the Bridge Model flips the lens by targeting the reward structure—what gets laughed at, validated, punished, or protected—so dignity stops being optional.

A. Level 1 — Personal Effort

This level matters because it prevents small harms from turning into identity wars. It has 6 core habits—PPP-RR-C.

i. Practise Radical Empathy

ii. Practise Flexibility During Meet-Ups

iii. Prioritise Repair Over Defensiveness

iv. Recognise Own Power and Share Love

v. Reward Honesty Not Performance

vi. Counter Misinformation and Encourage Fact-Checking

Example Scripts:

- Script: “Help me understand what you meant.”

- Script: “That landed as shaming, but I love you, nonetheless.”

- Script: “Can we talk and fix this?”

Personal accountability begins with compassion—for yourself and for others—and a commitment to staying informed. Recognise your position within social hierarchies: if you are light‑skinned, masculine‑presenting, or financially secure, you hold social capital. Use that privilege to protect, not to dominate. Knowing better is the first step to doing better. Avoid spreading misinformation by doing your own research and encouraging others to do the same. When a situation feels larger than it appears, pause, look deeper, and examine the forces at play. Share what you learn. Commit to honesty over performative lifestyles.

B. Level 2 — Small Groups

Harm spreads quickly when bystanders stay silent—or worse, respond with laughter. This level focuses on disrupting the “laugh track” that normalises cruelty.

i. Bystander Interrupts:

Bridge Builders use bystander interrupts—brief, calm interventions that break momentum—to stop shaming or humiliation. You don’t need a lecture—just remove the approval. Even a simple pause can shift the tone and create space for reflection.

- Script: “Let’s not shame him.”

- Script: “Pause—this is getting colourist.”

- Script: “We can disagree without humiliating anyone.”

ii. Bridge Builders must be peace and unity ambassadors in any group they belong to.

C. Level 3 — Community Systems

When the environment rewards cruelty, people adapt to cruelty.

- Community owners and managers should publish a clear code of conduct that explicitly bans exclusion, bullying, fetishisation, stigma, and misinformation.

- Community spaces must operate under a non-negotiable standard of inclusivity.

How to Use the Bridge Model in Real Life

1. Use Level 1 when conflict is interpersonal

Apply Level 1 when the issue is between two people, or when you notice your own defensiveness rising.

- “I’m not here to win—help me understand what you meant.”

- “I get my intention, but I also hear the impact. I’ll adjust.”

- “Before we spread this, what’s the source? Are we sure?”

2. Use Level 2 when harm is being normalised socially

Level 2 is for group chats, friend circles, party circles, and “scene spaces” where shaming becomes entertainment. Remember: Silence is endorsement.

- Bystander Interrupts: short corrections that stop harm without starting a war.

- Bystander interrupt scripts (fast + clean):

- “Let’s not shame him.”

- “That’s not fair—rephrase.”

- “We’re not doing that here.”

- “Pause. That’s lateral violence.”

- “We’re all brothers, bro, do better.”

- As peace and unity ambassadors, Bridge Builders promote healing and love: set the tone—compliment repair, de-escalation, and maturity.

3. Level 3 is for community and platform owners, managers, and admins

- Community Codes / Agreements should include:

- What’s banned (clear examples, not vague “be nice to each other”)

- What happens next (warnings, removal, restorative steps)

- Repair pathways (how someone can make amends without centring themselves)

- Non-negotiable inclusivity means:

- Marginalised voices aren’t optional add-ons—they guide standards.

- Disinformation and scapegoating are actively challenged.

- Safety and invitation aren’t based on popularity, masculinity, or status.

FAQ

They are very common, but not inevitable. Cultures can be redesigned. Minority stress theory explains why pressure increases internal sorting, but it also supports the case for building protective environments to counteract that stress (Meyer, 2003)[6].

Not always. Research on sexual racism shows that many so‑called “personal preferences” aren’t neutral tastes at all, but patterns closely tied to broader racist attitudes. When a “preference” excludes an entire group—whether by race or body type—it stops being a preference and becomes a prejudice (Callander et al., 2015)[1].

Silence ruins the space. Early calm interrupts stop harm from hardening into “this is just how we are here.” The Bridge Model encourages calling in—inviting repair—before calling out, when appropriate. But silence is never an option. Not ever.

Conclusion

Distrust thrives where hierarchies and silence dominate. Love is rebuilt through intentional practice—empathy, accountability, and systems that make dignity non-negotiable. Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model reminds us that unity isn’t a mood—it’s a shared discipline we practise, maintain, and protect together.

References

- Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3

- Dennis, A. C. (2025). Colorism and health inequities among Black Americans: A biopsychosocial perspective. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465251364373

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2023). Minority stress theory: Application, critique, and continued relevance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101579

- Hunt, C. J., Fasoli, F., Carnaghi, A., & Cadinu, M. (2020). Why do some gay men identify as “straight-acting” and how is it related to well-being?. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01650-4

- Johns, M. M., Pingel, E., Eisenberg, A., Santana, M. L., & Bauermeister, J. (2012). Butch tops and femme bottoms? Sexual positioning, sexual decision making, and gender roles among young gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988312455214

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 5. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Nowicki, G. P., Marchwinski, B. R., O’Flynn, J. L., Griffiths, S., & Rodgers, R. F. (2022). Body image and associated factors among sexual minority men: A systematic review. Body Image, 43, 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.08.006

- Thornton, M. C., Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Forsythe-Brown, I. (2017). African American and Black Caribbean feelings of closeness to Africans. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 24, 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2016.1208096