It’s Not “Toxic”—It’s Survival.

When people talk about internal hierarchies among Black gay and bisexual men, they are usually describing the informal ranking systems that dominate dating apps, friendship circles, nightlife, and common queer spaces. It is the unspoken rulebook of who gets chosen and who gets ignored based on specific traits: masculinity, skin tone, body type, and sexual role.

It is vital to frame this correctly from the start: this is not an argument that Black gay men are uniquely shallow or cruel. Rather, it is an acknowledgement of lived truth. And I’ve always believed that acknowledgement is the first step to solving any problem—no one seeks a solution to an issue they don’t believe exists.

What looks like a Black gay man’s “obsession” with rank is often a response to accumulated trauma and social pressure. Understanding why it happens is the first step to dismantling it.

What “Internal Hierarchy” Looks Like in Real Life

While the dynamics and intensity vary by city and generation, the “ranking system” usually relies on a set of predictable social currencies. In many Black gay spaces, these hierarchies are so visible and routinely enforced that they’re impossible to miss.

- Masculinity hierarchies: the “Masc4Masc” / “No fems” bloc.

- Sex-role hierarchies: the “Only Tops” bloc and “BornToBottom” exclusives.

- Body hierarchies: the “Gym Bros” / “No fats” bloc.

- Proximity to straightness: the “I don’t even have gay friends” bloc—DL/hood-coded, hyper-discreet, “first-time” identity branding.

- Proximity to whiteness: validation through being desired by White men, where fetishisation can get misread as love.

- Colour hierarchies: colourism—systemic preference for lighter skin and Eurocentric hair and facial-feature ideals.

- Class hierarchies: bougie vs “ghetto/ratchet” sorting and respectability policing.

- Ethnicity hierarchies: intra-Black ranking—e.g., “Yardie” vs “African,” “Foundational” vs migrant/“FOB” (fresh off the boat) distinctions.

These in‑community hierarchies shape everything from dating app behaviour and club doors to friendship circles in Black gay communities across Africa and the diaspora.

Why Hierarchies Show Up So Often in Black Gay Spaces

Multiple studies explain that these behaviours are not random; they are often psychological responses to specific stressors.

1. Performance of Hypermasculinity for Safety and Status

Research indicates that some gay men adopt hypermasculinity as protection against the shame and stigma of being labelled “soft” or “effeminate.”[4]

Hypermasculinity is an exaggerated performance of masculinity that overemphasises toughness, dominance, and emotional restriction—often used to gain status or to distance oneself from being perceived as feminine.

This is a form of compensatory behaviour where a gay man responds to stigma or personal insecurity by over-performing masculinity to offset shame. In practice, it often extends beyond exaggerated self-presentation: the performer may adopt rigid “masc” rules that also involve policing, excluding, or humiliating other gay men.

The problem is that this behaviour, instead of dismantling the oppression hurting him, ends up strengthening it—a “selling‑out” dynamic that prioritises external validation over solidarity and ultimately weakens the power and joy of community belonging.

2. Defensive Othering as a Plea for Belonging

Defensive othering is a specific kind of compensatory behaviour that works through intra-group distancing. It’s a deliberate social strategy that someone from a stigmatised group uses to distance themselves from that group to avoid the negative stereotypes or stigma associated with it.

Sometimes, this can take the shape of a gay man begging his straight friends:

“I’m gay, but I’m not like those kinds you hate. Please don’t treat me like them.”

Here, distancing is used to bargain for belonging—but he ends up relinquishing his own power to fund a system that oppresses him. Instead of challenging stereotypes, defensive othering fragments collective solidarity, making systemic change even harder.

Schwalbe et al. (2000)[5] call it a “strategy of adaptation that reproduces inequality.” It’s a survival tactic that ends up sustaining the very structures that oppress the group.

3. Internal Competition or Intraminority Stress

This is very similar to defensive othering, only that it happens internally—within the community.

Illustrative examples:

Defensive othering: A Black gay man refuses to attend Pride, saying, “I’m not gay like that,” using distance from visible queer expression as a bargaining chip for social acceptance.

Intraminority stress: At Pride, a Black gay man avoids being photographed with a gender-nonconforming person to signal he belongs to the “masc” group—reproducing hierarchy, tension, and exclusion inside an event meant to affirm community.

Again, this behaviour fragments community solidarity and weakens collective resistance. But it also increases psychological stress and feelings of isolation for the performer.

Research indicates that stress originating within gay communities, distinct from external homophobia, can contribute to poorer mental health outcomes for sexual‑minority men (Soulliard et al., 2023)[6].

4. Double-Ended Rejection—The No-Win Politics of Gay Belonging

Black gay men often face a particular kind of “double bind” around rejection—a no‑win situation where rejection can come from multiple directions at once, and trying to avoid it in one space can make it more likely to happen in another.

This plays out in both African and diasporan contexts, though the pressures take different shapes.

i. African Context (Nigeria, for example)

Obi keeps his life in compartments: family WhatsApp, work WhatsApp, and the one group chat where he can breathe. On a rare good day, he tells a few queer friends how he corrected someone who made a slur at a bar—small, but he’s proud. The replies come back flat: “Guy, be careful.” “Delete this chat.” One person stops responding altogether.

He understands the fear, but it still lands like rejection. Above ground, he must act like nothing about him is different. Underground, even courage has to be quiet. Safety becomes a kind of discipline—yet it doesn’t guarantee warmth, only survival.

ii. London/UK Diaspora Context

Obi is outside, dressed well, and finally in a room where he shouldn’t have to shrink. But the room has its own rules. In the mainstream crowd, he is desired—but not for his charisma, nerve, and talent. His Blackness and the fact of being African place him into a ready-made category. The category is desired, not him.

Later, in a smaller Black queer circle, the sorting continues—just in a different language.

“You went to Pride? Oh, I didn’t see you as that type of gay.”

That night, Obi stays awake, deleting all the sweet pictures he’d taken at the event. He cancels the date he’d planned with the drag friend he just met—someone who made him feel, for a moment, uncomplicatedly welcome. Though he can’t fully explain why he’s doing it, the pressure was palpable. He came for freedom. But even here, belonging still comes with conditions.

The Cost of Internal Hierarchies in Black Gay Communities

Participating in these hierarchies might offer short‑term validation (for example, getting the “hottest” partner), but the long‑term data is concerning.

a. Poorer Mental Health and Well-being

Studies on intraminority stress in gay communities link status competition—around masculinity, desirability, and social standing—to higher anxiety symptoms. This is even after accounting for other stressors (Maiolatesi et al., 2021)[2].

James and Bowling (2025)[1] found that internalised stigma—shaped by experiences of discrimination—was associated with greater fear of HIV testing and more reluctance to seek psychological help among gay and bisexual Black men.

b. Community Fragmentation

Community networks of support are vital for the well-being of minority groups. They help buffer minority stress by offering practical care[3], shared understanding, and a sense of safety in numbers. Belonging also reduces anxiety and loneliness by reminding people they are not carrying stigma alone.

But these unnecessary internal hierarchies undermine that protective function. They fracture community care and collective solidarity, replacing trust with suspicion and leaving people more isolated inside the very spaces meant to hold them.

c. Lateral Violence

Lateral violence happens when someone is made to feel powerless by a person or system with greater power. Instead of confronting the real source of harm, they redirect their anger sideways—toward people closest to them and with similar status. The “war” returns to the community, not because the community caused it, but because it feels like the safest place for the anger to land.

A simple way to picture it: when a parent beats a child, the child may turn around and beat a younger sibling. The pain is real—but it gets passed down the line. In communities, this often shows up as policing, gossipping, exclusion, undermining, and subtle hostility, turning peers into targets rather than allies.

d. Trauma Circulation

Covert acts of lateral violence—gossiping, sneering, rumour-mongering—over time, lead to widespread distrust and the frustration of being treated unfairly. If left unchecked, this distrust can harden into internalised contempt or suppressed hate.

In that atmosphere, intimacy can become purely transactional: sex with bodies, not connection, because genuine fondness feels risky or pointless. That is one way trauma circulates. People protect themselves by staying detached, but the detachment then injures others, who learn the same lesson and pass it on. What began as self-defence turns to culture: less empathy, more suspicion, and a community that struggles to offer the very care it needs to heal.

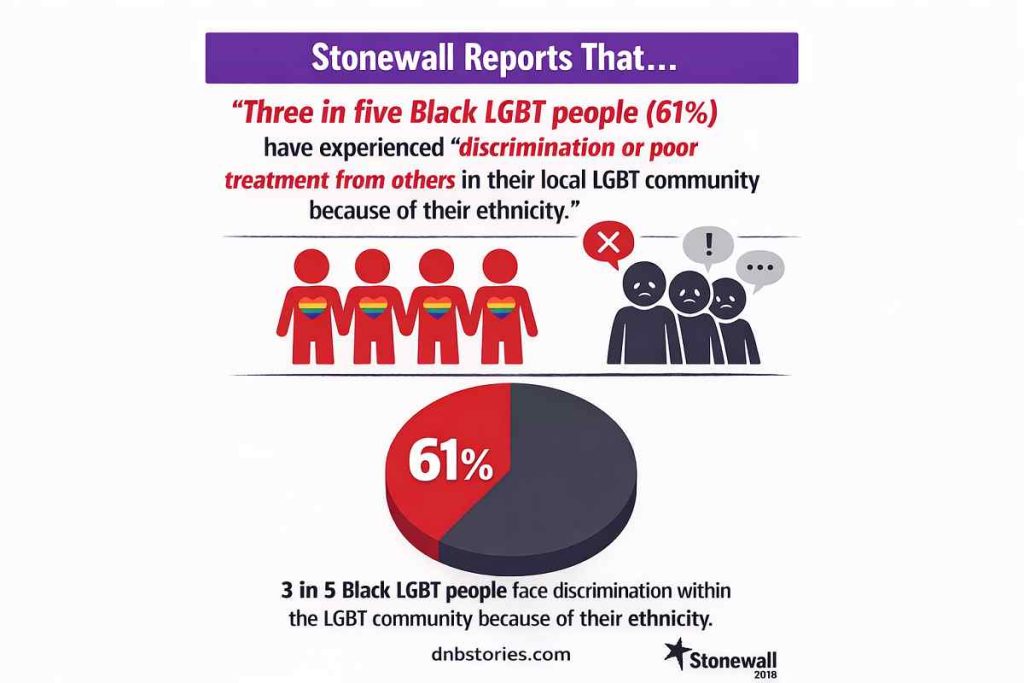

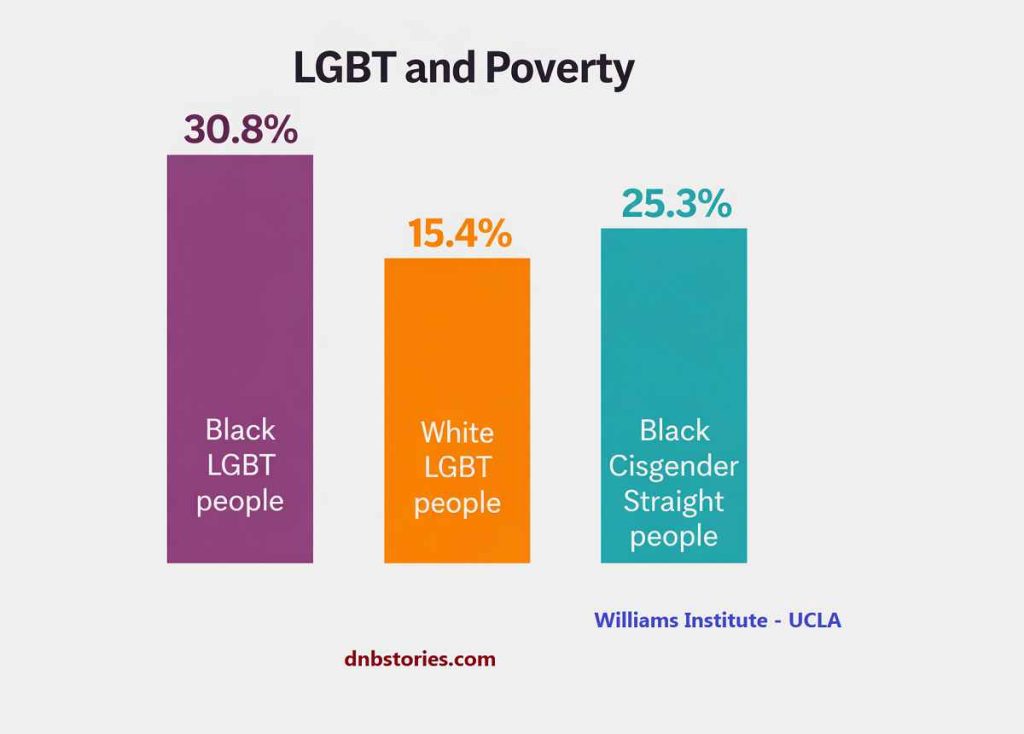

e. Increased Poverty Among Black Gay Men

In communities where being seen as “masc,” “dominant,” or “total top” can offer status and protection, individuals may feel pressured to spend their time, energy, and money maintaining an image rather than building long‑term security.

Additionally, a culture of shaming and stigma redistribution can discourage help‑seeking and reduce the likelihood of forming supportive partnerships or sustaining positive mentorship.

Rebuilding Trust and Solidarity in Black Queer Spaces

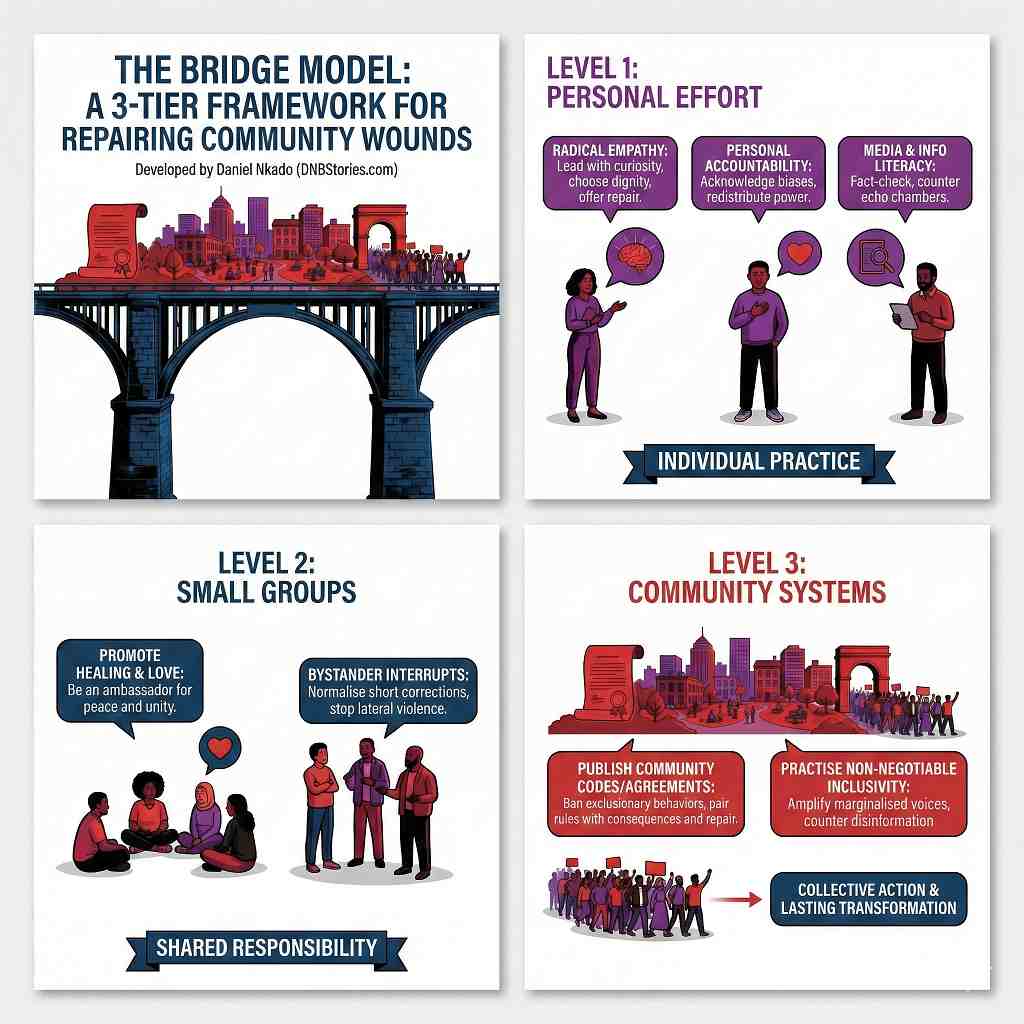

I developed The Bridge Model from the belief that lasting transformation begins with personal effort and grows through collective action. By linking three levels of change—Personal, Small Groups, and Community Systems—the model makes progress possible from any entry point: anyone can start where they are and still contribute to meaningful change. Rather than waiting for authorities or moralising at communities, The Bridge Model invites shared participation from the outset, treating trust and solidarity not as giant ideals to demand, but as responsibilities to practise together.

The Bridge Model — From Personal Change to Collective Action

Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model is a three-tier framework for repairing distrust and restoring love in Black gay communities by treating healing as a shared responsibility.

It argues that trust breaks across individual behaviour, small-group culture, and community-wide systems, so repair must happen across those same layers:

- Level 1 (Personal Effort) builds radical empathy, accountability, and media/info literacy to reduce harm and misinformation.

- Level 2 (Small Groups) reshapes the “scene layer” through solidarity and brief bystander interrupts to stop lateral violence.

- Level 3 (Community Systems) formalises protection with published codes/agreements, repair pathways, and non-negotiable inclusivity, so safety isn’t dependent on popularity or luck.

The aim is collective action and lasting transformation—moving empathy into action, and action into durable structures that protect dignity and sustain trust. Everyone in this framework is a Bridge Builder (informally, a Briguilder).

A. Individual-Level

This level rests on three core principles—compassion, accountability, and information literacy—which together produce six key habits:

- Practise Radical Empathy

- Practise Flexibility During Meet-Ups

- Prioritise Repair Over Defensiveness

- Recognise Own Power and Share Love

- Reward Honesty Not Performance

- Counter Misinformation and Encourage Fact-Checking

Examples:

- “Can we talk and fix this?” before cutting someone off.

- “That landed as shaming,” rather than “You’re toxic.”

- “Help me understand what you meant,” instead of assuming hostility.

- No mocking, no public dragging for entertainment.

- Actively fact-check information to avoid amplifying misinformation.

- Counter echo chambers politely when you come across them.

- Acknowledge own privileges and take steps to redistribute power (not stigma) in everyday decisions.

- Move from silent endorsement to active participation in challenging oppressive norms.

B. Small Groups

a. Stop lateral violence early with “bystander interrupts.”

- Normalise short interrupts:

- “Let’s not shame him,”

- “Don’t make ‘fem’ the punchline,”

- “We can disagree without humiliation.”

- Small corrections reduce the culture of covert aggression that destroys trust.

b. A Bridge Builder acts as an ambassador for peace and unity, promoting healing and care within the groups they belong to.

C. Community-Level

a. Publish Community Codes/Agreements

- A one-page code that bans the use of humiliating or shaming language, hierarchical sorting, policing or other exclusionary behaviours.

- Pair rules with consequences (warnings, time-outs, removal) and repair options (mediation).

b. Practise Non-negotiable Inclusivity

- Invest in community-driven spaces that amplify marginalised voices and counter disinformation.

- Promote fact-checking and content labelling to restore constructive dialogue.

Conclusion:

Trust and solidarity are forged through deliberate practice: individual empathy and accountability, mutual support in small groups, and community systems that guarantee fairness.

Pressures of survival have produced damaging hierarchies among Black gay men, where coping too often turns into shaming, policing, or exclusion. The task ahead is to replace these mechanisms with environments that uphold dignity regardless of appearance, wealth or masculine performance. Our worth is inherent, and belonging must be unconditional.

References

- James, D., & Bowling, A. M. (2025). Intersectional discrimination, internalized heterosexist racism, and health attitudes among gay and bisexual Black American men: A path analysis approach. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000878

- Maiolatesi, A. J., Satyanarayana, S., Bränström, R., & Pachankis, J. E. (2021). Development and Validation of Two Abbreviated Intraminority Gay Community Stress Scales. Assessment, 107319112110429. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211042933

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Quinn, K., Dickson-Gomez, J., DiFranceisco, W., Kelly, J. A., St. Lawrence, J. S., Amirkhanian, Y. A., & Broaddus, M. (2015). Correlates of Internalized Homonegativity Among Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 27(3), 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2015.27.3.212

- Schwalbe, M., Holden, D., Schrock, D., Godwin, S., Thompson, S., & Wolkomir, M. (2000). Generic Processes in the Reproduction of Inequality: An Interactionist Analysis. Social Forces, 79(2), 419–452. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/79.2.419

- Soulliard, Z. A., Lattanner, M. R., & Pachankis, J. E. (2023). Pressure From Within: Gay-Community Stress and Body Dissatisfaction Among Sexual-Minority Men. Clinical Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231186789

- Stonewall. (2018, June 27). LGBT in Britain – Home and Communities (2018). Stonewall. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/resources/lgbt-britain-home-and-communities-2018

Support Resources (UK & US)

- Black Minds Matter UK: Connecting Black individuals with free mental health support. blackmindsmatteruk.com

- National Black Justice Coalition (US): Civil rights organization dedicated to the empowerment of Black LGBTQ+ people. nbjc.org

- UK Black Pride: Europe’s largest celebration for African, Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American and Caribbean-heritage LGBTQ people. ukblackpride.org.uk

- Switchboard (UK): LGBTQIA+ Support Line. switchboard.lgbt