Black Gay Men: Vulnerability as Risk, Rejection as Danger

There’s a common, painful truth we rarely admit: a space can be full of people, noise, and movement — and still feel emotionally empty. The issue isn’t a lack of people—our numbers are solid. What we’re missing is soul: not the ghostly kind, but the emotional glue—trust, tenderness, mutual regard—that turns a room of faces into a community.

Black gay men are not cruel. Many of us carry love that is both weighted and genuine, but lack the channels to distribute it. Around us, a culture that prizes spectacle, fakery, and control dominates. Our first test of vulnerability was met with shame. So we adapt and perfect a persona. We learn to keep conversations shallow, hug without meaning, and laugh without feeling. We perform closeness under thick armour, allowing what should unite us to become a source of fear.

This is exactly the kind of social environment the Bridge Model is designed for: where love exists, but trust is too brittle for love to travel.

- Black Gay Men: Vulnerability as Risk, Rejection as Danger

- The Bridge Model: An Evidence‑informed Trust-Repair Framework

- The Bridge Model by Daniel Nkado Explained in a Glance

- Why Black gay spaces need a framework like this

- The Bridge Metaphor: Why "Bridge Builders" Matter

- Conclusion: Building Bridges That Support Everyone

- FAQ

- Copy/paste pledge/ bio script for Bridge Builders

- References

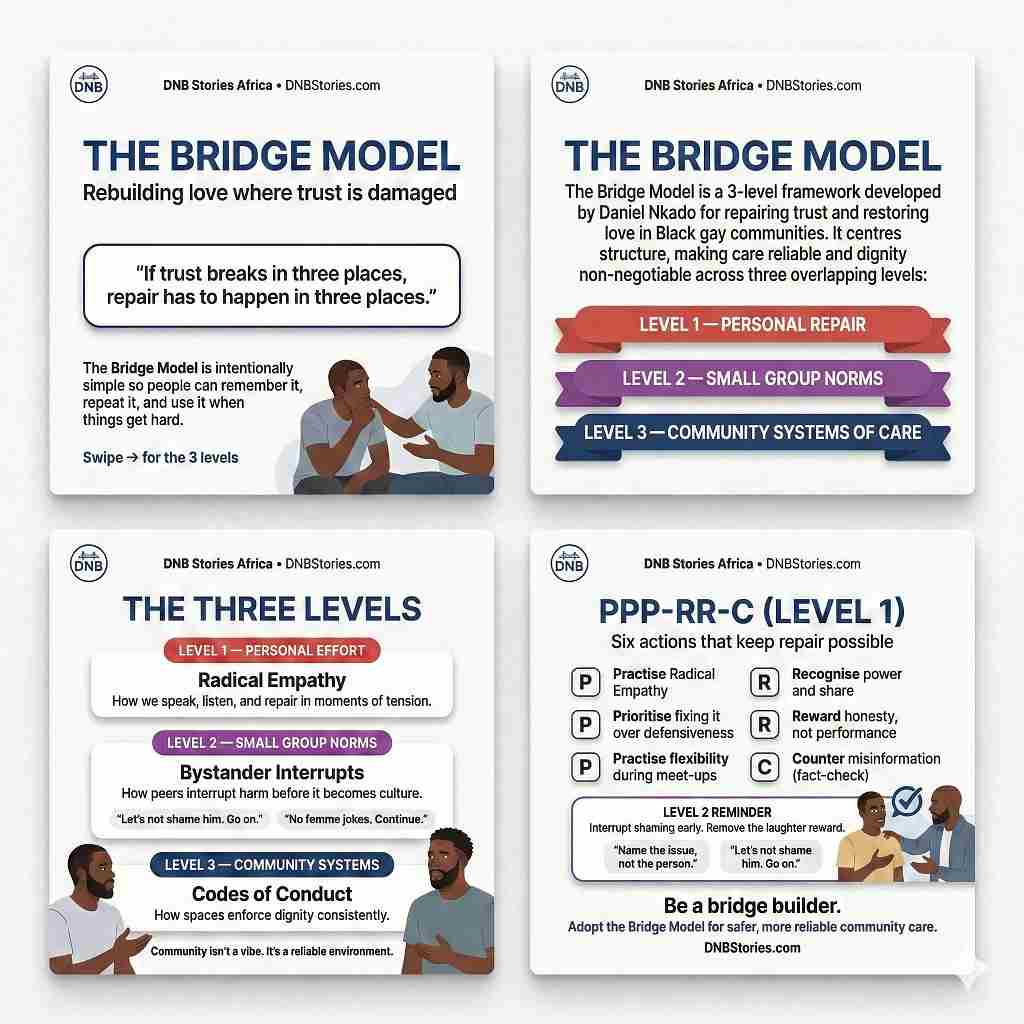

The Bridge Model: An Evidence‑informed Trust-Repair Framework

The Bridge Model is a 3-tier framework designed to rebuild love where trust has been damaged. It’s intentionally simple so people can remember it, repeat it, and use it when things get hard. The Bridge Model strengthens the channels that let care move without restriction.

“If trust breaks in three places, repair has to happen in three places.”

The Bridge Model operates on three distinct levels:

- Personal effort—how we speak, listen, and repair in moments of tension.

- Small-group norms—how peers interrupt harm before it becomes culture.

- Community systems—how spaces enforce dignity consistently.

This post explains the model in plain language, the psychology behind why it works, and how to put it into practice.

The Bridge Model by Daniel Nkado Explained in a Glance

Think of trust like a bridge between people. It doesn’t collapse from a single argument. It gives way after many years of untreated rot.

- People stop believing repair is possible.

- Bystanders normalise cruelty through silence.

- Some actively reward humiliation by donating laughter.

- Communities rely on “vibes” instead of standards.

Rebuilding a fallen system takes more than the soft advice to “be kinder.” When harm has hardened across many layers, the repair must be layered too — intentional, coordinated, and continually in motion.

a. Level 1 — Personal Effort

This level supports six core actions — PPP‑RR‑C — but any act or language of repair qualifies, so the list is technically inexhaustive.

It starts with Radical Empathy.

- Practise Radical Empathy

- Prioritise Fixing It Over Defensiveness

- Practise Flexibility During Meet-Ups

- Recognise Own Power And Share

- Reward Honesty, Not Performance

- Counter Misinformation By Encouraging Fact-Checking

b. Level 2 — Small Group Norms

Level 2 focuses on peer action that stops harm early. Harm endures because bystanders with the power to intervene remain silent.

Level 2 has two main arms:

- Bridge Builders use “Bystander Interrupts” to stop shame and humiliation at the source.

- Bridge Builders recognise their role as peace and unity ambassadors.

The Bridge Model: Bystander Interrupts

If cruelty earns laughter, it spreads. If cruelty meets interruption, it shrinks. This logic leverages the Bystander Intervention model—shifting peers from passive observers to active protectors (Darley & Latané, 1968)[2].

Interrupts are intentionally designed to be short. Bridge Builders use them to cancel shaming in real time while the speaker continues. Sometimes, the speaker may apologise, creating a “double gain” that teaches others to be mindful of their bias, too.

Examples of what “Bystander Interrupts” look like:

- “Let’s not shame him. Go on.”

- “Name the issue, not the person, baby.”

- “No femme jokes. Continue.”

This level works by destroying the reward system that feeds the culture of shaming and humiliation. This positions it as an exceptional strategy for protecting the most vulnerable people in the room. This group often includes younger men, newcomers, migrants, people without money, and people with less “market value”. These are people frequently told to develop thicker skin instead of being offered dignity.

The concept of Bridge Mode’s “Bystander Interrupts” aligns with shame resilience theory[3], which posits that moving away from shame requires naming it and fostering empathy (Brown, 2006)[1].

c. Level 3 — Community Systems

Level 3 is where a space stops being “a vibe” and becomes a container: predictable, fair, and safe enough for people to relax. It encourages community managers and platform admins to build codes of conduct that protect love and uphold the dignity of all members.

This document should define the rules, the moderation process, and the repair options for offenders seeking to make amends.

If you run a Telegram group, host events, moderate a community, or organise meetups, we encourage you to adopt this model for safer, more reliable community care.

Community isn’t a vibe. It’s a reliable environment.

Why Black gay spaces need a framework like this

1. Because shame spreads faster than care

Shame is cheap. It takes one joke, one side comment, or one remark with “subtweet energy” to dismantle safety. Care, however, is expensive when no one protects it. When people learn that vulnerability will be mocked, they don’t become “stronger”; they become guarded. They curate a persona, reduce honesty, and trade intimacy for control.

2. Because silence is an active endorsement

Most harm becomes “culture” not because everyone supports it, but because the majority stays silent. This is known in social psychology as pluralistic ignorance—where a majority of group members privately reject a norm, but incorrectly assume that most others accept it (Prentice & Miller, 1993)[5]. Silence is what turns repeated harm into a norm.

3. Because love collapses when dignity is negotiable

When Black queer belonging depends on hierarchies and status signals—hypermasculinity, wealth, or sexual role—intimacy becomes conditional. People stop building bonds and start managing reputation.

The Bridge Model counteracts this by changing the incentives. It makes care easier to practice, harm harder to spread, and accountability predictable rather than sensational.

For a breakdown of how masculinity gets rewarded or overlooked in Black gay spaces, see the Masculinity Anchors Model.

The Bridge Metaphor: Why “Bridge Builders” Matter

One perfect person doesn’t build a bridge. It is built by shared design and maintained by repeated action.

Bridge Builders are the people who:

- Keep conversations repairable.

- Interrupt harm early—without turning into bullies.

- Protect the emotional container of the group.

- Help communities move from “we should be better” to “here’s how we do here.”

Bridge Builders are not saints. They’re the builders of infrastructure. They don’t save communities. They give communities the tools to sustain themselves.

The “3-Second Rule” for Social Correction of Shaming

Interrupts work on a simple rule of efficiency:

- Intervene early.

- Intervene briefly.

- Intervene without spectacle.

If you wait until it becomes a pile-on, you’re late. Most harm is easiest to stop at the point of manufacture.

The Role of Bridge Builders in Restoring Community Trust

Bridge builders work at all three levels.

a. You transform conflict into repair: You move people from “I’m hurt” to a sentence that can be answered without humiliation.

b. You interrupt harm without becoming harm: You stop the behaviour, not destroy the person.

c. You protect the container even when it’s inconvenient: You defend standards even when the harmed person is unpopular, quiet, or exhausted.

Conclusion: Building Bridges That Support Everyone

The Bridge Model does not promise absolute softness or easy love. It commits to structure—making care reliable and dignity non-negotiable. Trust returns not through intention alone, but through repair we practise ourselves (Level 1), harm we refuse to entertain (Level 2), and systems that protect people consistently (Level 3).

Bridge builders make that reliability real: choosing interruption over silence, repair over spectacle, and standards over cruelty—so tenderness stays possible without becoming dangerous.

FAQ

Is this only for Black gay spaces?

No. The Bridge Model can be applied to any community facing layered pressures. However, Black gay spaces make the dynamics visible—masculinity policing, desirability hierarchies, stigma residue[4], and fragile belonging. The model applies anywhere trust is thin.

Does this replace therapy?

No. The Bridge Model is a community infrastructure designed to strengthen collective support. It complements, but does not replace, individualised clinical care.

What if people say codes of conduct feel “too formal”?

Formal is not the enemy. Unfairness is. The goal is a clear, transparent system that protects people from unpredictable social harm.

What if someone refuses repair?

Then Level 3 does its job. Repair is offered; it is not begged for.

Copy/paste pledge/ bio script for Bridge Builders

These ready‑to‑use scripts work for bios, pinned posts, flyers, and social cards—tweak as needed for a perfect fit.

We build bridges, not blame. We share love, not shame. We distribute power, not stigma. We repair, not cancel.

References

- Brown, B. (2006). Shame Resilience Theory: A Grounded Theory Study on Women and Shame. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3483

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025589

- Lane, W. B. (2020). Integration of Shame Resilience Theory and the Discrimination Model in Supervision. Teaching and Supervision in Counselling, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.7290/tsc020104

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Prentice, D. A., & Miller, D. T. (1993). Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243

- Smith, R. E., Vanderbilt, K., & Callen, M. B. (1973). Social Comparison and Bystander Intervention in Emergencies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(2), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1973.tb02705.x