In the quiet corners of the human heart, where feelings begin, and identities take root, few questions stir as much curiosity—and confusion—as this: Can a straight person ever become gay, or develop same-sex attraction?

Picture a young man named Ade, raised in Lagos, where masculinity is often measured by how many girls one can charm. For years, Ade dated women, confident in his straightness. But one day, he meets a man who stirs emotions he never expected. At first, he’s confused. Then afraid. Then, slowly, accepting. Or not.

So what happened to Ade? Did he “turn” gay—or was this part of him always there, quietly waiting to be known?

Stories like Ade’s echo across the world, from Lagos to London, stirring debates that blend science, emotion, and identity. To answer this question truthfully, we must look at both the biology of attraction and the fluid nature of human experience.

By the way, modern science recognises the brain as the true seat of emotion, so forgive the metaphorical use of the heart as the organ of love in this article.

The Science of Attraction: Born this way or Shaped by life?

Most scientists agree that sexual orientation isn’t something people choose. Studies over the years show that it’s shaped by a mix of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors—mostly happening before birth.

While researchers have not discovered a single “gay gene,” a large-scale study published in Science found that genetics may explain up to 25% of same-sex behaviour. The rest? It’s a mix of biology and environment— like hormone levels and variations before birth and life experiences (such as family, culture, and social surroundings). Together, these factors shape how a person’s sexuality develops and is understood and expressed.

But science also acknowledges something else: sexual fluidity.

This means that while most people’s orientation remains consistent, a smaller group experiences changes over time—sometimes because of emotional bonds or self-discovery. Some studies have also acknowledged that fluidity appears more often in women but exists across all genders (Mittleman, 2023)4.

It’s not about choosing to switch sides—it’s more like realising a new door within yourself has quietly opened. Still, attempts to force that door shut—like through “conversion therapy”—have repeatedly been proven harmful. Major psychological associations around the world condemn such practices, noting that while they do not work, they also often lead to anxiety, depression, and shame. Our hearts, after all, are not machines that can be reprogrammed. They are living, evolving parts of who we are.

Discussing reprogramming further, a term called “neuroplasticity” describes the brain’s ability to form new connections and strengthen old ones. In simple terms, the more you repeat a thought or action, the more your brain learns it—making it feel easier and more natural over time.

However, sexual orientation is not consciously changeable through neuroplasticity. Although the brain can change and adapt throughout life, research has not confirmed that this can undo the deep biological patterns, most of which were formed before birth, that shape sexual orientation.

Sexual Orientation Exists on a Spectrum

For decades, society tried to divide human attraction into neat boxes — straight, gay, or bisexual. But science, psychology, and lived experience now tell a different story: sexual orientation isn’t fixed or binary; it exists on a wide and fluid spectrum.

Every person’s pattern of attraction — emotional, romantic, or sexual — falls somewhere along this continuum. Some people feel exclusively drawn to one gender, while others experience varying degrees of attraction to more than one. This diversity doesn’t mean confusion; it reflects the natural complexity of human desire.

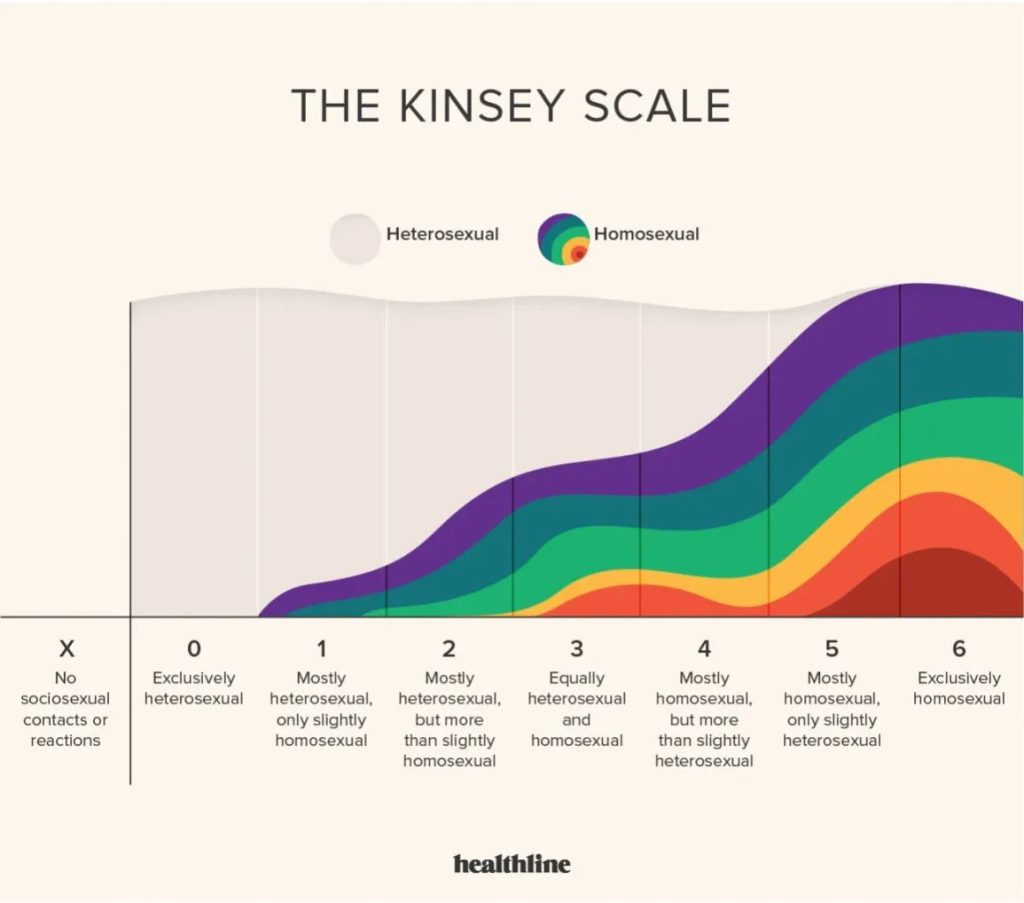

The idea of a spectrum first gained traction through Alfred Kinsey’s pioneering research in the 1940s. His Kinsey Scale placed sexuality on a seven-point range from 0 (completely heterosexual) to 6 (completely homosexual), revealing that many people don’t fit strictly at either end. Modern psychology has expanded this idea through tools like the Klein Sexual Orientation Grid, which considers emotional and social attractions over time — showing that orientation can subtly shift with experience and self-awareness.

Biology supports this continuum, too. Genes, hormones, and brain development shape attraction before birth, yet they don’t create rigid categories. Even identical twins can have different orientations, proving that environment and experience also play roles. Studies today — from neuroimaging to large-scale surveys — continue to show that many people fall into the “in-between” spaces: mostly straight, mostly gay, or fluid.

Seeing sexuality as a spectrum doesn’t erase identity — it frees it. It allows people to express themselves without guilt, to love who they love without needing to “pick a side.” In truth, the human heart was never meant to live in boxes; it was meant to explore the full range of connection, colour, and possibility.

How Life Experiences Influence Attraction

Take Fatima, a woman from Nairobi who married young and lived what many called a “normal” life. In her mid-30s, she met a female colleague who awakened something deep inside her. The connection felt real, even though it defied everything she once believed about herself.

Was Fatima “turning” gay? Science would say no—she was likely uncovering a bisexual side that had always been there, hidden beneath layers of social conditioning.

Her journey wasn’t easy. It involved tears, therapy, and difficult conversations. But on the other side of fear came peace—and authenticity. Stories like Fatima’s and Ade’s remind us that sexuality isn’t a straight line. It’s more like a river—flowing, shifting, and sometimes carving new paths where we least expect.

While sexual orientation is rooted in biology, life experiences can shape how attraction is felt, expressed, or understood. Our environments, relationships, and emotional growth all play roles in how we navigate the spectrum of sexuality.

We’re born with biological blueprints — shaped by genetics, hormones, and early brain development — that influence who we’re drawn to. But experiences throughout life can affect how those predispositions unfold. For example, someone who grows up in a community where same-sex attraction is taboo might suppress or ignore it, while another person in a more open environment might explore and embrace it freely. The orientation itself doesn’t change — the expression of it does.

The Role of Relationships and Self-Discovery

Romantic and emotional connections often awaken aspects of attraction we hadn’t previously noticed. Studies, including research from the University of Sydney (2021) and psychologist Lisa Diamond’s long-term work on sexual fluidity, show that people sometimes report subtle shifts in who they’re attracted to over time — usually following meaningful relationships or moments of self-reflection. For instance, someone who once identified as straight might later recognise deeper same-sex attractions after forming a close emotional bond with a person of their sex(Diamond, 20163; Dar-Nimrod, 2021)2.

Romantic encounters, emotional bonds, or even exposure to new ideas can lead individuals to re-evaluate or broaden their sense of attraction (fluidity). However, these experiences do not create fluidity from nothing — they simply shape how an existing biological predisposition is expressed. Research shows that while some people experience shifts in attraction or identity over time, others remain consistent throughout life (Morandini et al., 2021)5.

In essence, life experiences can move someone along the spectrum of attraction, but the spectrum itself is built on a biological foundation set long before birth.

A man is more likely to be gay with each older brother he has!

That statement refers to what scientists call the “fraternal birth order effect.” According to this discovery, for every older brother a man has, the chance he’ll be gay increases by about 33%.

It’s not because of family influence or how the brothers were raised — it’s linked to biological factors during pregnancy. Scientists think the mother’s immune system may react slightly differently with each male pregnancy, changing how certain brain proteins develop in later sons. That could nudge both sexual orientation and gender expression in a more feminine direction (Balthazart, 2017)1.

However, this is not causative for all cases (e.g., it doesn’t explain how “first-son gays” like me came about).

So, Can a Straight Person Ever Become Gay?

The honest answer is not exactly, but they can discover that their sexuality is more complex than they once thought.

Most people’s orientation remains stable throughout life, but for some, sexual fluidity allows for genuine shifts in attraction or self-understanding. That doesn’t mean one “changes” orientation; it means they’ve grown into a fuller version of themselves. In truth, love and attraction don’t always obey logic. They unfold mysteriously, reminding us that being human is about exploration, not perfection.

Final Thoughts

In a world that loves categories, sexuality exists to remind us that the human spirit resists tidy boxes. We love, we grow, and sometimes we change in ways even science can’t fully explain. What matters most isn’t the label we wear, but the honesty with which we live our truth. Because in the end, every story of love—gay, straight, bi, or in-between—is simply a story about being human.

Whether you’ve always known your truth or are still discovering it, what matters most is compassion—for yourself and others. No one should be shamed for discovering, questioning, evolving, or embracing who they are.

References

- Balthazart, J. (2017). Fraternal birth order effect on sexual orientation explained. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(2), 234–236. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719534115

- Dar-Nimrod, I. (2021) Do you think you’re exclusively straight?, The University of Sydney. Available at: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2021/08/20/do-you-think-you-re-exclusively-straight-.html.

- Diamond, L. M. (2016). Sexual Fluidity in Male and Females. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-016-0092-z

- Mittleman, J. (2023) ‘Sexual Fluidity: Implications for Population Research’, Demography, 60(4), pp. 1257–1282. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-10898916.

- Morandini, J. S., Dacosta, L., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2021). Exposure to continuous or fluid theories of sexual orientation leads some heterosexuals to embrace less-exclusive heterosexual orientations. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94479-9