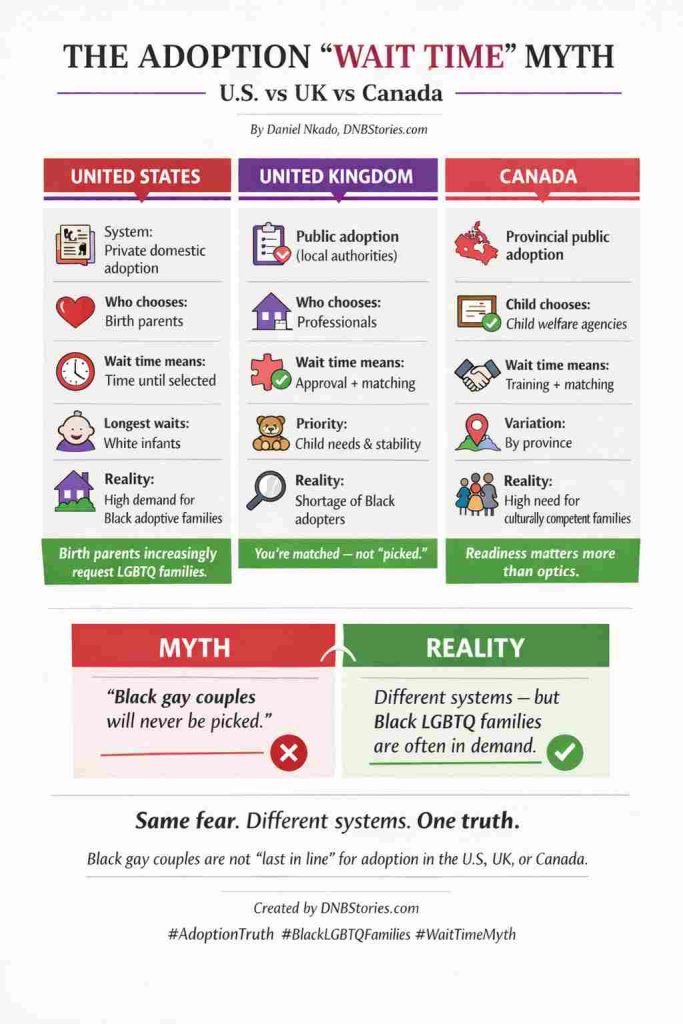

Black Gay Couples and the ‘Wait Time’ Myth

For many Black gay couples considering adoption, one fear looms larger than the rest: “We’ll never be chosen.”

This belief circulates globally—across WhatsApp chats, online forums, and informal advice networks—shaping decisions in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. While each country operates under a different legal framework, the fear travels easily, reinforced by older stories of exclusion, racial bias, and homophobia.

However, current data and agency reports reveal a disconnect between this fear and reality. Far from being universally overlooked, Black LGBTQ couples are often well-positioned within modern adoption frameworks.

Whether through birth-parent choice in U.S. private adoption or professional matching in UK and Canadian public systems, the “wait time myth” persists not because it reflects current statistics, but because it reflects yesterday’s barriers.

Black LGBTQ Adoption: What ‘Wait Time’ Really Means

To understand why the myth is inaccurate, one must understand that adoption wait times are not a single, universal measure of suitability. Instead, they are structural outcomes shaped by:

- The Type of System: Private (birth-parent choice) vs. Public (state/provincial matching).

- Demographics: The race and age of children needing placement.

- Supply vs. Demand: The availability of approved families versus the number of waiting children.

Wait time is not a moral ranking of who is “wanted”—it is a calculation of capacity. To understand how these patterns operate in real life, let’s examine the adoption systems across three key Western countries—the U.S, UK and Canada.

The United States: Private Adoption and Demand Dynamics

In the U.S., domestic infant adoption typically operates through private agencies where expectant birth parents review family profiles. The “wait time” here is largely defined by the demographics of the child.

The Statistical Reality of Black Adoption

There is a documented imbalance in the U.S. system. White infants are in high demand, leading to long wait times for families seeking them. In contrast, Black children are significantly overrepresented in the system.

Black children represent only about 14% of the U.S. child population but account for roughly 22–23% of those in foster care—a disparity compounded by the ongoing shortage of Black adoptive families (AFCARS, 2023)[1].

Black gay couples often experience what adoption professionals call the “Unicorn Effect”. Because there are too few Black adoptive families, they face far less competition than white couples, and many Black birth parents intentionally seek families who can offer cultural continuity and protect their child from racism. Combined with research showing that same‑sex couples are four times more likely to adopt than heterosexual couples (Gates, 2015)[4], this dynamic makes Black LGBTQ parents highly sought after—resulting in significantly shorter wait times, especially for those open to adopting Black children.

Many Birth Parents Now Pick Gay Couples

The idea that birth parents hesitate to choose gay fathers is becoming outdated. As early as the 2000s, research showed many birth parents specifically requested placement with gay couples (Brodzinsky et al., 2002)[2]. Today, with public support for same-sex adoption remaining strong over the last five years, gay couples are often seen as intentional and emotionally open—uniquely prepared to help children navigate stigma (Equaldex, 2024)[3]. For Black gay couples looking to adopt a Black infant, this also means offering vital racial and cultural continuity.

The UK System: Public Adoption and Professional Matching

The UK operates a fundamentally different system. Most adoptions are coordinated through Local Authorities (public sector) and Regional Adoption Agencies (RAAs), rather than private birth-parent selection.

How Matching Works in the UK

In the UK, you are not waiting to be “picked” by a birth mother. Instead, a social worker assesses your capacity to meet a child’s needs.

Because Black children and those of mixed heritage often wait the longest—due to a shortage of culturally matched families—Black gay couples represent a vital opportunity. For these children, the goal is a permanent home where their racial identity is mirrored, affirmed, and protected. In this context, a Black LGBTQ couple demonstrating readiness, stability, and cultural competence becomes a high‑priority match, not a ‘risky’ option.

Canada: Provincial Systems and Public Pathways

Canada’s adoption landscape is governed at the provincial and territorial level, primarily centred on public child-welfare systems (e.g., Children’s Aid Societies).

What ‘Demand’ means in the Canadian Context

Similar to the UK, the specific profiles of children in care shape adoption demand. Indigenous and Black children are significantly overrepresented—particularly in Ontario and Nova Scotia. This creates an urgent need for families who can provide cultural continuity. Social workers prioritise placements that preserve identity and community ties.

Because Black LGBTQ couples bring the intersectional experience of navigating minority identities, a trait increasingly valued by Canadian social workers looking for resilient placements, they occupy a strong position in the Canadian adoption landscape (Golombok et al., 2014)[6].

Why Black Gay Couples Are Essential

Despite the geographic differences, a clear pattern emerges across the U.S., UK, and Canada:

- Overrepresentation of Black kids: Black children remain disproportionately represented in foster care systems across the U.S., UK, and Canada.

- Underrepresentation of Black families: Black adoptive families are consistently in short supply.

- High Participation: LGBTQ adults are statistically the most likely demographic to pursue adoption.

- Intersectional Advantage: Black gay couples sit at the intersection of these realities; in systems that prioritise stability and cultural continuity, they are not peripheral — they are essential.

- Positive Outcomes: Long‑term studies show children raised by gay fathers experience strong psychosocial outcomes, with no disadvantages compared to peers.

Real Barriers to Black Gay Adoption

While the “wait time” fears are often exaggerated, real challenges exist.

It’s important to separate structural barriers from societal bias. Some birth parents or social workers may hold “colour‑evasive” or assimilationist views (Goldberg et al., 2007)[5], and gay couples can face dual discrimination from racism and homophobia. Geography also plays a role, as access to affirming agencies varies between urban and rural areas. Still, these are hurdles—not walls. With the right agency support and preparation, Black gay couples remain highly viable—and often highly sought‑after—adoptive parents.

Second-Parent Adoption for Gay Couples

Many same-sex parents still face expensive legal hurdles to secure their rights, such as the case of “second-parent adoption” to ensure both fathers (or mothers in the case of a lesbian couple) secure equal legal recognition—even when married. In some jurisdictions, marriage alone does not automatically grant equal parental status—especially if only one parent is biologically related to the child. Although second‑parent adoption can be expensive and time‑consuming, it functions as a legal safeguard rather than a barrier; couples can adopt first and then complete the step to fully protect their family’s rights (Minkin, 2025)[7].

Practical Strategies for Prospective Gay Parents

Regardless of the country, Black gay couples can navigate the system effectively by:

- Choosing Affirming Agencies: Specifically look for accreditation (such as the HRC’s All Children – All Families seal in the U.S.) or agencies with explicit anti-racist statements.

- Leading with Cultural Competence: Clearly articulate how you will support the child’s racial identity. This is a major asset in matching assessments.

- Understanding the System: Know if you are navigating birth-parent choice (U.S.) or professional matching (UK/Canada) and adjust your profile or preparation accordingly.

Gay Adoption in Nigeria

Same-sex unions are criminalised in Nigeria, making adoption by gay couples legally impossible. Some Nigerian states allow single men to adopt under strict conditions—such as prohibiting them from adopting girls—but identifying as gay while attempting to adopt attracts severe legal risks, including imprisonment. For members of the Nigerian diaspora, these restrictive laws often shape fears about adoption. However, it’s important to recognise that Western countries offer very different opportunities.

Conclusion

The belief that Black gay couples will “never be picked” persists because fear travels faster than facts. While adoption systems differ across the U.S., UK, and Canada, none are structurally designed to exclude Black LGBTQ families.

In reality, the demographics of children waiting for homes often place gay couples in high demand. For Black gay couples ready to parent, the question is no longer “Will we ever be chosen?”—it’s “Are we ready to begin?”

References

- AFCARS. (2023). The AFCARS Report: Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/afcars-report-30

- Brodzinsky, D. M., Patterson, C. J., & Vaziri, M. (2002). Adoption Agency Perspectives on Lesbian and Gay Prospective Parents. Adoption Quarterly, 5(3), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1300/j145v05n03_02

- Equaldex. (2024). Support for same-sex adoption (2024) | LGBTQ+ Surveys | Equaldex. Equaldex.com. https://www.equaldex.com/surveys/support-for-samesex-adoption

- Gates, G. J. (2015). Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples. The Future of Children, 25(2), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2015.0013

- Goldberg, A. E., Downing, J. B., & Sauck, C. C. (2007). Choices, Challenges, and Tensions: Perspectives of Lesbian Prospective Adoptive Parents. Adoption Quarterly, 10(2), 33–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/j145v10n02_02

- Golombok, S., Mellish, L., Jennings, S., Casey, P., Tasker, F., & Lamb, M. E. (2014). Adoptive Gay Father Families: Parent-Child Relationships and Children’s Psychological Adjustment. Child Development, 85(2), 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12155

- Minkin, R., Braga, D., Hurst, K., Mandapat, J. C., & Greenwood, S. (2025, June 12). Same-sex parents raising kids. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2025/06/12/same-sex-parents-raising-kids/