Intro: Understanding Black Gay Masculinity

Across major Western cities—such as London, New York, and Toronto—many Black gay men recognise an exhausting pattern: the constant evaluation of their masculinity through a straight‑coded template, where social legitimacy is easily granted to those who “pass.” In this context, proximity to heterosexual norms—not authenticity—determines masculine recognition.

However, a notable contrast appears across many parts of the Global South. Many African gay men—especially those socialised on the continent—seem less invested in seeking validation from straight peers, and some explicitly frame their masculinity as equal to—or even exceeding—that of certain heterosexual counterparts.[5]

This raises a key question: why then do some Black gay men in safer Western contexts still treat straightness as the standard for masculinity—and even appear to honour straight authority over their own expression?

This article introduces the Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) to explain why pressure for straight approval persists, moving beyond individual “preferences” to examine the social processes that define, reward, and police masculinity within Black communities.

- Intro: Understanding Black Gay Masculinity

- A. Straight Masculinity vs. Queer Masculinity

- B. Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model – MAM

- C. Social Masculinity vs. Biological Masculinity

- D. The MAM Model: Key Contributions and Limitations

- 1. Conditional Acceptance in Gay Spaces

- 2. Anchor Devaluation—Why Masculine Spaces Feel Cold

- 3. Code‑Switching as Contextual Competence in Practice

- 4. Femmephobia as Structural, Not Personal

- 5. Policing, Shaming, and Normalised Harm

- 6. Pass–Fail System of Black Gay Masculinity

- Critical Nuances and Limitations of the MAM Model

- Masculinity Anchors Model vs. Hegemonic Masculinity Theory

- E. Towards A Healthier Masculine Recognition

A. Straight Masculinity vs. Queer Masculinity

To understand the dominance of straight masculinity over Black queer masculinity—and the Black gay man’s persistent pursuit of straight validation—we must examine what straightness represents across different geopolitical contexts.

1. Straight Masculinity in Africa

In many African contexts, straightness is not recognised as the benchmark for masculinity or treated as a source of masculine authority. While some African gay men adopt a “straight‑acting” exterior to navigate public spaces safely, seeking validation from straight men—or pursuing straight association as a source of prestige—remains uncommon.

Within many African queer communities, queerness itself carries status, often associated with keen perception, competence, and creative distinction. Having straight friends can support a straight‑acting performance, but rarely viewed as a flex. In fact, visible proximity to straight men or straight‑dominated spaces can increase risk by inviting scrutiny, comparison, gossip, and intensified pressure around women and marriage (Mbah, 2019)[7].

2. Straight Masculinity in Western Contexts

By contrast, some Black gay men in Western contexts treat proximity to straight life as the closest marker of “real” masculinity—one that rapidly increases desirability and social respect within their communities. This dynamic elevates straightness as the benchmark for masculinity in Black queer spaces where this mindset dominates, even as the existence of feminine straight men remains largely unacknowledged.

This logic pushes some Black gay men to pursue straight validation with earnest intensity as a shortcut to the top of the queer masculine hierarchy. Yet by seeking approval from a heteronormative order that has no real space for them—rather than drawing authority from their own queerness—they end up reinforcing the very stigma and homophobia they hope to escape.

Why Straight Masculinity Rules Western Queer Spaces

Western straight masculinity is not innate but a historical construct built on systems of exclusion and control—particularly those tied to slavery. For Black men denied political and economic power, physical dominance became the most accessible path to masculine recognition. Plantation hierarchies reinforced this by rewarding dominant traits and circulating myths of hypersexual Black men, framing masculinity primarily as bodily power.

Over time, masculinity fused with heterosexual performance and bodily control, forming a gatekeeping structure that offered recognition only to those who obeyed its rules while excluding those who didn’t conform. Within this system, queerness is cast as a failure of manhood, fuelling a self‑sustaining cycle of stigma and homophobia.

Straight masculinity rests on a fragile foundation: it cannot fully validate queer men without undermining its own logic. To recognise queer masculinity as equally legitimate would expose masculinity as a performance rather than a birthright—destabilising the hierarchy itself.

Black Gay Men and the Pursuit of Straight Acceptance

In Western contexts, many Black gay men learn early that aligning with straight men can offer protection and elevate social standing—even when it requires sacrificing their own authenticity.

With this mindset, Black gay men who gain access to straight social circles—access that is mostly conditional and needs constant renewal—often mistake this proximity as evidence of high status or market value. Straight men who recognise this dynamic quickly assume the authority offered on a platter and begin policing Black gay men’s behaviour: You can move with us, as long as you’re not like the other soft, feminine gays.

In response, a queer man—often more intelligent, more attractive, or more socially adept than the person policing him—accepts this conditional inclusion without hesitation, sacrificing his identity to oppression. Thank you for accepting me—I won’t let you down.

He returns home and begins editing his life—deleting photos, cutting off friends, distancing himself from people like him. He shames and humiliates them, often more harshly than his straight bosses ever would.

Gay Men and The Straight Validation Trap

Straight approval of queer masculinity operates on fragile terms. Straight men often withdraw it the moment a gay man’s presence triggers masculine threat or raises the risk of association. Because Black masculinity carries significant political weight, Black men must continually negotiate and defend it. Masculine alliances form when interests align, but they remain conditional: few straight men will risk their own standing for a gay man without a clear and meaningful return.

B. Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model – MAM

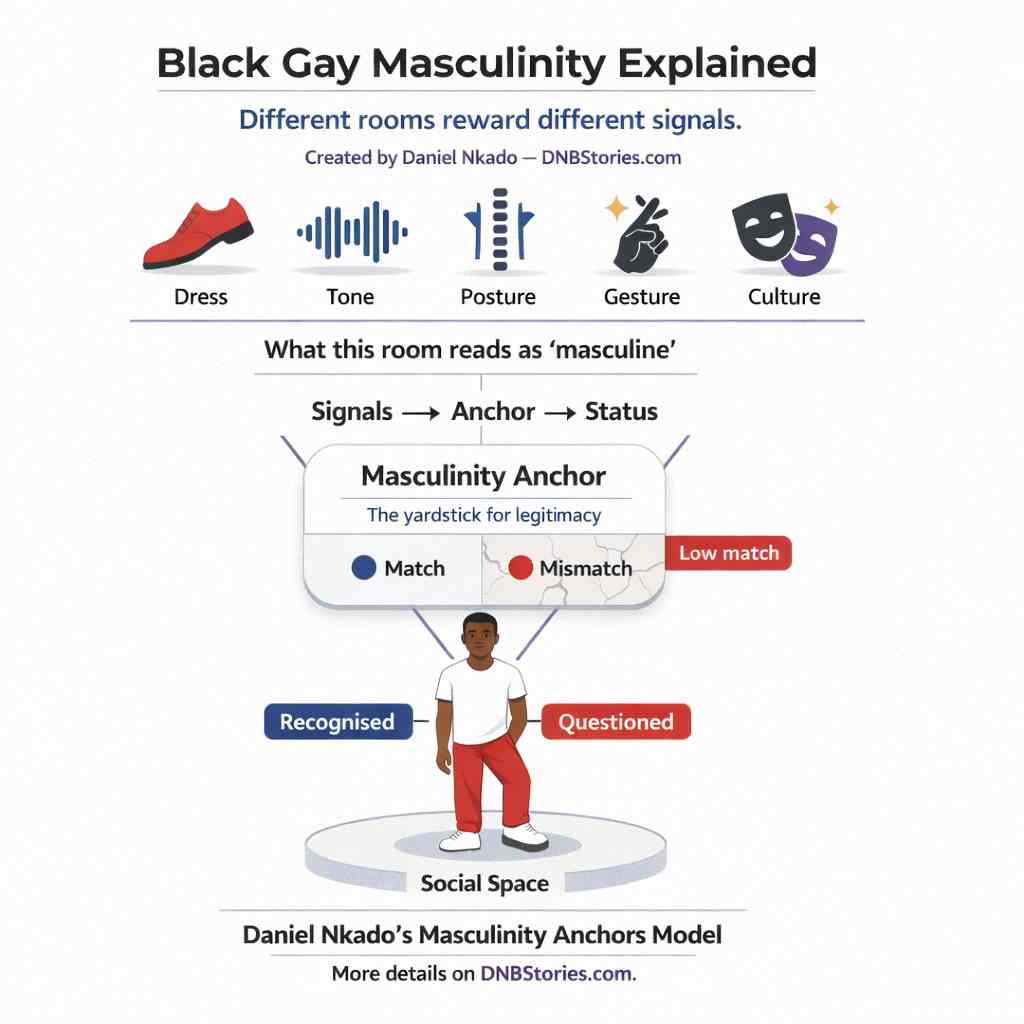

Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) treats Black queer masculinity as something men must actively secure depending on context, rather than naturally possess. Masculine legitimacy is achieved by mobilising recognised signals and references—such as heterosexual approval, social power, economic status, or cultural authority—that together form an anchor of credibility.

Every social space recognises and rewards specific signals or cues. These signals function as references. References combine to construct an anchor—the standard for assessing a queer man’s masculinity to determine whether a space recognises him as legitimate. When he deploys enough references to support a robust anchor, he “passes” within that space; when he does not, legitimacy becomes unstable.

In its simplified public‑education form, Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model identifies two primary anchors: achievement and performance.

Black Gay Masculinity Anchors and Signals

Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model names two primary anchors of masculinity that shape Black queer experience across African, Western, and diasporic contexts.

The two primary anchors of Black queer masculinity are:

- Achievement-Based Masculinity (ABM)—What you do or have done.

- Performance-Based Masculinity (PBM)—How you look or act.

1. Achievement-Based Masculinity—Receipts

Masculinity “counts” here when it is tied to competence and contribution. This can come in the form of responsibility, provision, stability, track record, usefulness, leadership, education, age, career progress, or problem-solving.

Because the ABM anchor does not require the active and continuous enactment of references, it tends to produce greater perceived stability and lower psychological distress.

This anchor commonly dominates in role- and responsibility-based social settings. These include family and kinship systems, older Black communities, and many African contexts where obligation and achievement stabilise masculine status.

2. Performance-Based Masculinity—Cues

For this anchor, masculinity “counts” when it is legible in real time. It describes the evaluation of masculinity through perceptible markers or signs such as voice, posture, emotional restraint, dominance cues, physicality, sexual scripting, and straight-acting references.

Because recognition depends not just on the cues themselves but on how they are performed, masculinity here remains fragile and mentally demanding. This anchor often dominates in high-visibility urban scenes. Examples include dating apps[4], nightlife economies, and professional settings where masculinity must be quickly proven to strangers.

Masculinity Anchors and Common Reference Points

a. Achievement‑Based Masculinity—References

ABM is judged by receipts. The louder the receipts, the stronger the anchor.

Common ABM references/signals

- Career/enterprise — work reputation, business success

- Material stability — income, assets, family wealth

- Education/credentials — degrees, academic success

- Leadership/responsibility — roles, duty, reliability

- Creator output — projects, artistry, innovation, founder track record

- Status/access — titles, elite networks, institutional legitimacy

- Integrity/mentorship — trustworthiness, guidance, eldership

b. Performance‑Based Masculinity—References

Unlike Achievement‑Based Masculinity, PBM is evaluated through legible cues and signals.

PBM references/cues

- Dominance cues — control of space, assertiveness

- Proximity to straightness — stories of “being with the boys,” social media videos or images of hanging out with straight friends.

- Straight-passing references — straight‑acting, passing labour

- Macho aesthetics — hardness, anti‑softness cues

- Physical presentation — body, muscularity, grooming

- Sexual scripting — top‑as‑legitimacy, role status

- Respectability cues — polish, accent, style, discipline

- Scene fluency — charisma, social intelligence, code knowledge

Straight‑Anchored Queer Masculinity

Straight‑Anchored Queer Masculinity describes a form of performance‑based masculinity in which straightness itself becomes the main source of masculine legitimacy. Instead of being one signal among many, straightness is treated as an authority to submit to and borrow from. Through straight‑acting behaviour, being read as straight, or emphasising closeness to straight men and straight hierarchies, the performer enters queer spaces already feeling credentialed.

This “straight labour” allows him to reorganise the room’s authority around himself by positioning himself as closest to the “real” standard of masculinity. However, because this legitimacy is borrowed rather than internally grounded, it remains fragile and requires constant vigilance. When straight masculinity is no longer treated as singular or dominant, the anchor weakens, and the performance loses its power to police, shame, or control others.

C. Social Masculinity vs. Biological Masculinity

Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) approaches Black queer masculinity not as a biological trait or fixed identity, but as a form of social masculinity.

Here, Black queer masculinity appears as a negotiated status produced by social settings rather than a biological fact or fixed identity. Spaces elevate particular signals as proof of manhood, and the distribution of these references determines who gains legitimacy and authority[1].

By centring anchors—the external standards through which a setting confers masculine recognition—MAM shows that everyday preferences and intra‑community tensions do not arise in isolation. It also clarifies why some group harms feel so normalised—the system compels them, rather than individuals premeditating them (Schrock & Schwalbe, 2009)[10].

A Gay Man Cannot Validate His Own Masculinity

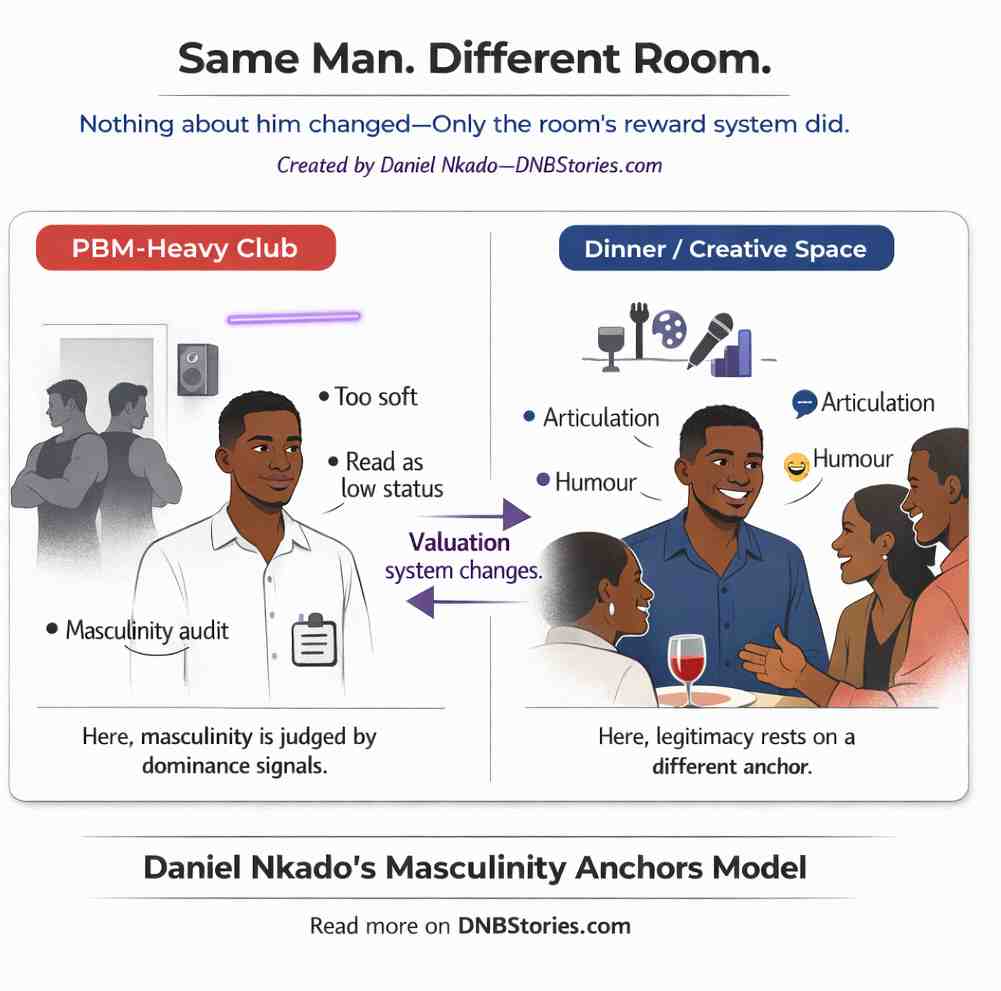

According to Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM), masculinity isn’t self‑certified. Rather, it’s a social status granted or denied by the space around him. A man can’t simply approve his own masculinity in social terms; he can only adjust his signals to match what the setting recognises as proof. Whether those signals are accepted or rejected depends entirely on the room’s valuation system.

Research on mascing culture demonstrates how gay men actively adjust their self‑presentation to align with the masculine incentives rewarded in queer spaces, reinforcing Nkado’s view of masculinity as socially managed rather than biologically fixed (Rodriguez et al., 2016)[9].

Anchor Stacking, Devaluation and Contextual Competence

Daniel Nkado’s Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) looks at masculinity as a flexible status that men manage based on context, rather than a fixed image.

a. Anchor Stacking: This refers to the use of secondary legitimacy cues to thicken and protect a primary anchor of masculinity under evaluation. Signals that fall outside the primary anchor, if correctly deployed, can still help strengthen and stabilise it, especially in uncertain or high‑risk settings.

For example, in an ABM context, a man may already hold institutional markers such as a banking career and a PhD in Accountancy. His fluent speech and deep voice—signals more commonly rewarded in PBM settings—do not establish legitimacy in this space on their own, but they reinforce the existing anchor by reducing friction and buffering against scrutiny.

b. Anchor Devaluation: In spaces dominated by the same masculine cues—such as a club filled with muscular, emotionally restrained men—those signals lose value through over‑saturation. This produces anchor devaluation, turning the space into an engine of cold interactions, guardedness, micro‑aggressions, and hyper‑competitiveness. When everyone offers the same proof of masculinity, legitimacy becomes scarce.

c. Contextual Competence: This describes the ability of a Black gay man to read which anchors a space rewards, and to adjust, stack, or suppress masculine signals—receipts or cues—so legitimacy remains intact across settings. It explains how men manage risk by aligning their presentation with each room’s valuation system rather than relying on a fixed expression of masculinity.

Contextual incompetence, by contrast, occurs when a man misreads the room—deploying signals that are irrelevant, overvalued, or penalised—producing friction, scrutiny, or social failure despite effort or intent.

D. The MAM Model: Key Contributions and Limitations

Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) helps bring clarity to several Black gay dynamics people feel but struggle to name—especially in performance-based masculinity (PBM) settings.

Here are six core Black gay social dynamics the Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) helps clarify:

1. Conditional Acceptance in Gay Spaces

MAM helps explain why the rules frequently shift from room to room in Black gay spaces. What earns you respect in one setting might cause you exclusion or judgment in another. This helps clarify why traits like femininity, softness, or intellectualism do not share universal acceptance across multiple queer spaces. Acceptance depends on whether those traits align with the anchors a room rewards. Femmephobia, for instance, may be intensified in PBM‑dominant settings, where dominance and macho aesthetics function as primary anchor pillars. Yet the same person can move into a different space—one where polish, accent, or cultural fluency form the anchor pillars—and gain legitimacy with ease. What changes is not the individual, but the valuation system governing the room.

2. Anchor Devaluation—Why Masculine Spaces Feel Cold

In environments saturated with the same masculine cues—muscularity, stoicism, sexual dominance—those signals lose value. MAM names this Anchor Devaluation, explaining why such spaces often become guarded, transactional, and hyper‑competitive. When everyone performs the same masculinity, legitimacy becomes scarce.

3. Code‑Switching as Contextual Competence in Practice

MAM reframes code‑switching not as inauthenticity, but as contextual competence in action. As men move between spaces with different anchor systems, they adjust which signals they emphasise, soften, or suppress to remain legible. This might mean leaning into polish and wit in one room, restraint and dominance in another, or intellectual fluency elsewhere (Bridges & Pascoe, 2014)[2].

4. Femmephobia as Structural, Not Personal

MAM shows that femmephobia isn’t just individual bias—it’s produced by anchor systems that reward dominance and penalise softness. Traits marked as “too feminine” fail not because they lack value, but because the room’s anchors don’t recognise them as legitimate proof.

5. Policing, Shaming, and Normalised Harm

People often shame or police others not because they’ve thought it through, but because the space they’re in—group chill, nightclub, or gay dating app—quietly demands it. The harm feels normal because it isn’t fully deliberate—it’s the automatic enforcement of whatever that room already values (Pascoe, 2005)[8].

6. Pass–Fail System of Black Gay Masculinity

Masculine legitimacy for Black gay men often operates on a pass–fail basis. For some masculinities to be approved, others must be excluded or marked as insufficient. MAM makes visible how legitimacy holds value precisely due to the uneven distribution.

Critical Nuances and Limitations of the MAM Model

The Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) is a mid‑range analytic tool, not a universal theory of queer masculinity. It explains how gay men secure masculine legitimacy in highly evaluative settings, not all forms of gendered experience.

MAM is context‑specific and works best where masculinity must be continually proven through recognisable cues. It does not fully capture intimacy, desire, affect, or broader structural forces, and should be used alongside other frameworks to address those dimensions.

Masculinity Anchors Model vs. Hegemonic Masculinity Theory

Hegemonic masculinity theory, developed by R. W. Connell[3], explains masculinity as a stable hierarchy that privileges dominant forms while marginalising others. The Masculinity Anchors Model (MAM) builds on this framework by focusing on how men gain masculine legitimacy in specific social contexts—particularly for Black queer men, whose masculinity often feels to be under constant evaluation.

Rather than asking what masculinity looks like in general, MAM asks what counts as proof of masculinity in a given space, highlighting how legitimacy shifts depending on context, culture, and audience.

This positions MAM as a practical, situational complement to hegemonic masculinity theory, offering a clearer lens for understanding code‑switching, conditional acceptance, and shifting standards of legitimacy in queer social life.

E. Towards A Healthier Masculine Recognition

If external anchors currently determine masculine legitimacy, a healthier future requires loosening their grip. Rather than assembling signals to satisfy an unreliable external system, Black gay men can build masculinity from within—grounded in self‑definition, relational integrity, and internal coherence. The Masculinity Anchors Model clarifies why this shift feels difficult: as long as dominant spaces control the terms of recognition, they can withdraw legitimacy at will. Naming the system makes redesign possible. Masculinity anchored within stops waiting for approval from standards never built to recognise it fully, and begins to define its own power.

Internally-Anchored Gay Masculinity—Masculinity From Within

Black gay men need a masculinity that requires neither external valuation nor validation—what Nkado calls Internally Anchored Masculinity (I‑AM). Unlike anchor‑dependent masculinity, which relies on external cues and social approval to feel legitimate, I‑AM is self‑authorising. It does not rise or fall with a room’s valuation system, nor does it require dominance or comparison to remain intact. Instead, it offers freedom within social life—the ability to move through spaces without surrendering one’s sense of self to their shifting standards.

Black Gay Men on Embracing Their Queerness

Perhaps it is time Black gay men stopped treating queerness as a deficit to compensate for and began recognising it as a source of insight, range, and creative agency. Queerness trains people to read social rules closely, build chosen kinship, and craft identity with intention rather than inheritance—capacities that translate into emotional intelligence, cultural fluency, and resilience. In Black queer life especially, it also reclaims masculinity from external audits by expanding what counts as strength: care, honesty, softness, accountability, and the courage to live without permission. By embracing queerness as power, Black gay men can stop auditioning for external recognition and start building belonging on their own terms.

For addressing trust and emotional safety in Black gay spaces shaped by masculinity tensions, the Bridge Model offers a three‑level, evidence‑informed framework for rebuilding community care and love.

Conclusion

The Masculinity Anchors Model shows that Black gay men do not inherently crave straight validation. Instead, MAM explains how social reward systems train many gay men to navigate the authority of straight masculinity for access, safety, and status. When social spaces continually reward anchors built around straight‑coded norms, alignment becomes a strategy for reducing risk as much as increasing desire. Shifting the conversation away from individual behaviour and toward the systems that govern legitimacy creates conditions for healthier patterns of expression.

References

- Anderson, E. (2010). Inclusive Masculinity: The Changing Nature of Masculinities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203871485 (Original work published 2009)

- Bridges, T., & Pascoe, C. J. (2014). Hybrid Masculinities: New Directions in the Sociology of Men and Masculinities. Sociology Compass, 8(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12134

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Forbes, T. D., & Stacey, L. (2022). Personal Preferences, Discursive Strategies, and the Maintenance of Inequality on Gay Dating Apps. Archives of Sexual Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02223-1

- Jesper Bjarnesen, Boulton, J., Uroš Kovač, Mbah, N., Whitehouse, B., & Wyrod, R. (2023). Of Masks and Masculinities in Africa. Afrikaspectrum/Africa Spectrum, 58(3), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/00020397231217520

- Manalansan, M. F. (2006). Queer Intersections: Sexuality and Gender in Migration Studies. International Migration Review, 40(1), 224–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00009.x

- Mbah, N. L. (2019). African Masculinities. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.270

- Pascoe, C. J. (2005). “Dude, You’re a Fag”: Adolescent Masculinity and the Fag Discourse. Sexualities, 8(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460705053337

- Rodriguez, N. S., Huemmer, J., & Blumell, L. E. (2016). Mobile Masculinities: An Investigation of Networked Masculinities in Gay Dating Apps. Masculinities & Social Change, 5(3), 241. https://doi.org/10.17583/mcs.2016.2047

- Schrock, D., & Schwalbe, M. (2009). Men, Masculinity, and Manhood Acts. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115933