What Masculinity Can’t Confront, It Tries to Control

In parts of the UK Black gay scene—especially where “mandem” performance overlaps with down-low (DL) secrecy—conflict often shifts from open disagreement into covert power tactics. These tactics include information control, intimidation by implication, emotional manipulation, and strategic social isolation.

This analysis examines how masculinity threat, stigma, and informal surveillance can transform intimate relationships into reputational battlegrounds, where preserving a heterosexual‑coded image often becomes the primary measure of “winning,” regardless of cost.

By contrasting this with Nigerian masculinity scripts—where cultural norms largely encourage men to address conflict through direct confrontation—this analysis clarifies how different social environments shape both the expression and management of conflict.

Article Scope: What This Article Is and What It Isn’t

This article offers a focused community-anchored analysis of how masculinity performances can function as a form of social technology—used to regulate behaviour, manage reputation, and exert control within specific networks. It adopts a harm‑minimisation lens, aiming to help readers recognise coercive dynamics and support the rebuilding of safer, more accountable community norms. This analysis is not a diagnostic guide, nor does it suggest that all down‑low men are inherently abusive. It does not endorse harassment, vigilantism, or forced “outing,” and it makes no claim to define or speak for the entire UK Black gay community.

Key Terms and Social Context

a. “Mandem” and the London Roadman Masculinity Register

While “mandem” originates in Multicultural London English (MLE) as a largely neutral reference to one’s male friends, its meaning can shift in social practice. In certain spaces, it has come to signify a style of hyper‑performative, roadman‑influenced Black British masculinity, organised around emotional restraint, dominance cues, and rigid respect–disrespect hierarchies.

Where this register carries social status—for example, within some Black gay scenes—these norms can shape how Black men interpret and manage power, vulnerability, and conflict (University of York, n.d.)[8].

b. Down-low (DL) Culture and “Straight-Passing” Labour

“DL” (down‑low) describes men who engage in same‑sex intimacy while maintaining a heterosexual public identity. While this often represents a necessary survival strategy under conditions of high risk, in comparatively safer contexts, such as the UK, it can create significant information asymmetry. In these dynamics, one partner holds disproportionate control over a relationship’s visibility, allowing them to exploit secrecy as a form of power—and in some cases, weaponise it to maintain dominance.

Reproducing DL lifestyles in relatively safer conditions—where a shared need for secrecy no longer applies—shifts the DL mask from personal protection to social leverage, used to manage status and exert control within a relationship.

DL-to-DL Relationships Can Balance Power

One proposed way to mitigate this dynamic is for DL men to engage exclusively with others who also perform DL identities, thereby restoring symmetry around secrecy and risk. When both partners share similar visibility constraints, they reduce the need for constant explanation, policing, or one‑sided control over the relationship’s narrative.

Covert Conflict Management in UK Black Gay Spaces

In many UK Black gay male spaces, conflict often goes underground—not because confrontation is absent, but because visibility itself carries risk. Three sociological forces help explain why.

First, the concept of precarious manhood treats masculinity as a fragile status that men must continually prove and protect[9]. Public challenges can threaten that status—particularly when there is risk of visible embarrassment or loss—making open conflict seem dangerous.

Second, hegemonic masculinity explains how social hierarchies reward those who embody the dominant masculine ideal within a given context [2]. In some UK Black communities, this ideal often privileges calm, emotionally restrained, and non‑reactive dominance. Men who control situations rather than openly confront them.

Third, the theory of minority stress explains why visibility itself can feel dangerous. Stigma produces chronic vigilance, expectations of rejection, and pressure to conceal[5]. All of these increase the emotional risk of direct confrontation.

Together, these forces create a culture in which covert management of conflict becomes the smart, masculine, and self‑preserving choice. Power is exercised not through shouting matches but through silence, implication, and control over who is seen, heard, or quietly erased.

Covert Aggression in the UK vs. Open Confrontation in Nigeria

In some UK Black male contexts, relational and social aggression—such as damaging someone’s reputation, spreading rumours, gossiping, or quietly excluding them from social networks—has become a recognised mode of masculine power. These indirect strategies allow men to assert dominance, as defined within this context, while maintaining the appearance of emotional control and social composure.

By contrast, many Nigerian masculinity frameworks stigmatise these indirect behaviours in men, often labelling them as petty or distinctly unmanly. In this context, masculine credibility relies more on direct confrontation—through verbal assertion and physical presence—where men articulate grievances and defend honour face‑to‑face.

A common Nigerian saying captures this ethos succinctly. “If you want to talk to me, talk to me directly, like a fellow man—stop going round the corners.”

This divergence highlights that masculinity is not a fixed identity, but a locally constructed performance shaped by differing norms of visibility, silence, and respect.

Hypermasculinity and the “Mandem” Persona in the UK

In London’s Black urban masculinity ecosystem, the “mandem” performance operates simultaneously as a stigma shield—protecting inclusion within straight Black circles—a dominance signal that discourages challenges before they take shape, and a passport to belonging, granting access to male‑coded networks and closer proximity to other high‑status mandems.

While this posture offers protection on the street, in queer intimate contexts, it can become a relational weapon. It discourages negotiation, punishes vulnerability, and frames basic emotional needs as “femininity.” The mask ceases to be a form of self-presentation and becomes a system of relational governance.

DL Power Dynamics and the Social Weight of Secrecy

DL life is heavily shaped by the politics of “passing.” However, intense secrecy—especially in contexts where fear cannot be openly explained or accounted for—reshapes relationship dynamics by restricting partners’ autonomy and framing “exposure” as the ultimate threat. Because preserving a heterosexual public image and continued association with straight male peers functions as a high‑value social asset, it becomes a site of power struggle, rewarding those who can successfully control the narrative and manage visibility (McCune, 2014).

Black Gay Men in the UK: Passing as a Career Strategy

The DL power dynamic often becomes especially pronounced in spaces where social mobility is pursued through entertainment economies—such as music, nightlife, Black film, and informal social businesses. In these arenas, where traditional educational or corporate pathways may feel inaccessible or insufficient, reputation and masculine credibility operate as vital forms of capital. Association with visibly straight male peers signals marketability, toughness, and cultural legitimacy, while any perceived deviation from heteronormativity risks professional exclusion. In this context, heterosexual presentation and proximity are not merely personal identities but strategic assets that must be carefully curated and protected.

Respect for straight masculinity functions less as admiration than as a form of risk management—reflecting the high stakes of visibility in industries where rumours travel fast, access is informal, and social death can precede economic loss.

Queerness, Visibility, and the Myth of Professional Risk

This perspective often rests on outdated assumptions about what queerness “costs” a man. In contemporary UK cultural industries, being queer is not automatically a career liability. While discrimination persists and risks vary by sector, visibility can also expand opportunity: commissioners and audiences increasingly value distinctive voices, authenticity, and representation—particularly for Black stories that have long been under‑resourced and under‑amplified. If a certain performance has been treated as the only safe route, it is worth asking what it has actually delivered—and what it has quietly taken. For many queer Black men, embracing queerness can shift power: from managing suspicion to building presence, from hiding to speaking in a register that is genuinely their own.

Masculinity Threats and Covert Control Tactics

In the Black gay male contexts described above, Mandem and DL personas often overlap, such that a threat to one is experienced as a threat to the other. Perceived risks of outing, increased queer visibility, emotional vulnerability, or being read as “feminised” are not merely personal anxieties but structural dangers. To avoid compounding these risks, conflict in such relationships frequently bypasses open disagreement and instead shifts toward covert forms of control. These strategies allow power to be exercised without triggering exposure or destabilising masculine credibility.

What Covert Control Can Look Like In Real Life

When dominant masculinity norms discourage open conflict, power often shifts into indirect forms of control. Rather than addressing disagreements face‑to‑face, dominance is exercised through everyday emotional and relational dynamics—gossip, spreading rumors, damaging reputations, and socially excluding others.

In relationship contexts, covert control can manifest in several interrelated forms:

a. Information Control

When direct conversation feels too risky, information becomes a proxy for power.

- Selective truths and strategic omissions

- “You can’t say that” rules that limit expression

- Narrative editing: “You’re imagining it” / “You’re too sensitive”

b. Emotional Manipulation

When feelings can’t be named openly, they get managed indirectly.

- Guilt loops and intermittent validation

- Humiliation disguised as “banter”

- Love‑bombing followed by withdrawal

- Gaslighting: repeated distortion of reality that erodes trust in your own perception

c. Coercion and Intimidation

When confrontation is avoided, masked threat replaces dialogue.

- Explicit or implied threats to reputation, safety, or social standing

- Withholding affection, access, or information as punishment

- In UK law, controlling or coercive behaviour is recognised as a serious form of abuse in intimate and family relationships (see: UK Government factsheet—statutory guidance framework)

d. Dependency Engineering

When autonomy feels threatening, dependence becomes the fallback.

- Creating emotional, financial, or housing reliance

- Isolating you from people who “ask too many questions”

- Making stability contingent on compliance or silence

Closeting Is Not Abuse. Control Is.

This distinction is critical. Harm emerges not from secrecy itself, but from the unilateral use of secrecy to regulate, restrict, or dominate another. Many individuals choose—or feel compelled—to remain closeted to ensure safety, livelihood, or social survival. My Model of Dynamic Disclosure outlines five practical modes of disclosure that Black gay men may adopt across different contexts and spaces, reflecting the complexity of negotiating visibility. However, closeting becomes coercive when one person imposes it unilaterally within a relationship and uses it to regulate a partner’s behaviour, restrict their autonomy, or extract compliance through the threat of exposure or the exploitation of this fear.

In such cases, what may have begun as a protective strategy shifts into a mechanism of control—no longer a neutral condition, but a form of relational domination.

Nigerian Masculinity and the Politics of Public Justice

In dominant Nigerian heterosexual scripts, men typically defend their masculine status through public assertion—via verbal dominance, community-sanctioned discipline, and visible acts of reputation defence (Benebo et al., 2018)[1].

However, in the context of queerness, the dynamics shift dramatically. Nigeria’s criminalisation of same-sex intimacy—rooted in colonial-era laws and reinforced by contemporary legislation—combined with pervasive societal stigma, means that queer men often prefer to handle threats of exposure without attracting attention. Yet even within this climate, homophobic violence rarely occurs in public view. Gangs that target queer individuals often lure victims into secluded areas before attacking. This is not merely a tactic of evasion; it reflects a cultural logic in which public confrontation is not just about physical dominance but about justice.

In Nigerian public life, fighting in the open invites witnesses. Elders and bystanders often intervene, asking, “What is the matter?” In such moments, the outcome of a confrontation typically shifts from physical strength to the judgment of the crowd. Intimidating someone weaker or younger brings shame, not honour. An innocent man can cry in public to affirm his truth without compromising his masculinity. In fact, so long as people judge his emotion as sincere, it can enhance his honour—his vulnerability framed not as weakness, but as a testament to his integrity.

Homophobic Violence in Public Places in Nigeria

Even in cases of homophobic violence in the open in Nigeria, the question often arises: “Did you catch him in the act?” Without proof, the aggressor often earns blame. Public parading and shaming largely occur only when someone catches the two men in the act of same-sex intimacy.

The demand for “proof” does not protect anyone. It merely sets the threshold for what bystanders treat as punishable, believable, or worthy of public disturbance. The “caught in the act” logic can also fuel a culture of active surveillance. As documented in a 2016 Human Rights Watch report, one activist described how neighbours became “hunters,” entering homes at night in search of individuals in “compromising positions.” In such cases, the objective is not simply to respond to an act, but to produce evidence—or the appearance of it—that can legitimise violence, public shaming, and coercive control. The insistence on proof becomes less about justice and more about justification. A way to rationalise harm under the guise of moral or legal authority.

Queer-to-Queer Conflict Resolution in Nigeria

In Nigerian queer communities, where external threats such as criminalisation, raids, and public exposure make discretion essential for survival, trust‑based circles often form around mutual protection and clearly defined boundaries. Within these circles, people mostly prefer direct communication—naming harm, clarifying misunderstandings, and negotiating limits—as a harm-reduction strategy.

Many queer Nigerian men view indirect conflict—when not softened by humour—as sneaky and threatening, especially when based on vague or unsubstantiated claims that undermine masculine norms of directness and open confrontation.

Structural barriers to public confrontation mean that direct assertion occurs only where safety allows. But most conflicts do not require spectacle to be resolved. What matters is communicating a grievance directly to the person responsible, ensuring they understand that harm has occurred. Their response often determines the outcome. Naming offence is commonly received as a sign of respect rather than aggression. Where a relationship is not valued, disengagement—quietly moving on without retaliation—is typically preferred over escalation.

Harmful Power Tactics in Some UK Black Gay Circles vs. Nigerian Contexts

These are not fixed individual traits or cultural absolutes, but recurring patterns of power shaped by specific social conditions.

In UK Black gay networks where “mandem” hypermasculinity intersects with DL (down-low) secrecy, power is often exercised through covert control.

Dominance strategy of UK “mandem”/DL-coded networks:

- Covert control: strategic secrecy, covert planning, and sometimes “enemy-friend” positioning to manage access and outcomes.

- Intimidation-by-implication: veiled threats, silent punishment, emotional withdrawal.

- Narrative management: controlling who knows what, when they know it, and how events are framed.

- Emotional manipulation: “mind games” that erode clarity, confidence, and agency.

In Nigerian gay men’s circles, particularly within trust-based queer networks, power struggles tend to be more overt.

Patterns of Power Tactics in Nigerian queer networks:

- Audience-based success signalling: fashion, connections, visibility, media influence.

- Open rivalry “gay power-tussles”: contests over influence, desirability, and access.

- Visible dominance: direct confrontation or public social performance; power is asserted visibly rather than through hidden manoeuvring.

Secret Sabotage As The Way of ‘Snakes’

Within many Nigerian queer social circles, the most serious breach of communal ethics is not open rivalry but covert planning. Someone suspected of moving in secrecy—gathering information, setting traps, quietly undermining others—is often branded a snake. The metaphor does real work. Snakes do not announce themselves, do not move in groups, and cannot be trusted to behave predictably.

To be labelled a snake is therefore not simply to be called dangerous. It leaves a mark of moral unreliability that makes someone socially unfit for friendship. Unlike open power tussles, which depend on readability and shared audiences to function, secret manoeuvring introduces asymmetry and uncertainty. Once intentions become opaque, trust collapses—not only between rivals, but across entire networks.

In such conditions, even close associates may withdraw, recognising that proximity to hidden moves carries risks they cannot see, measure, or control.

Neutralising Manipulative Control: Four Practical Communication Strategies

These approaches can reduce escalation, but if there’s intimidation, stalking, threats, or coercive control, prioritise safety planning and specialist support. The UK government recognises coercive control in law and professional guidance as a serious and cumulative form of abuse, not a minor interpersonal dispute.

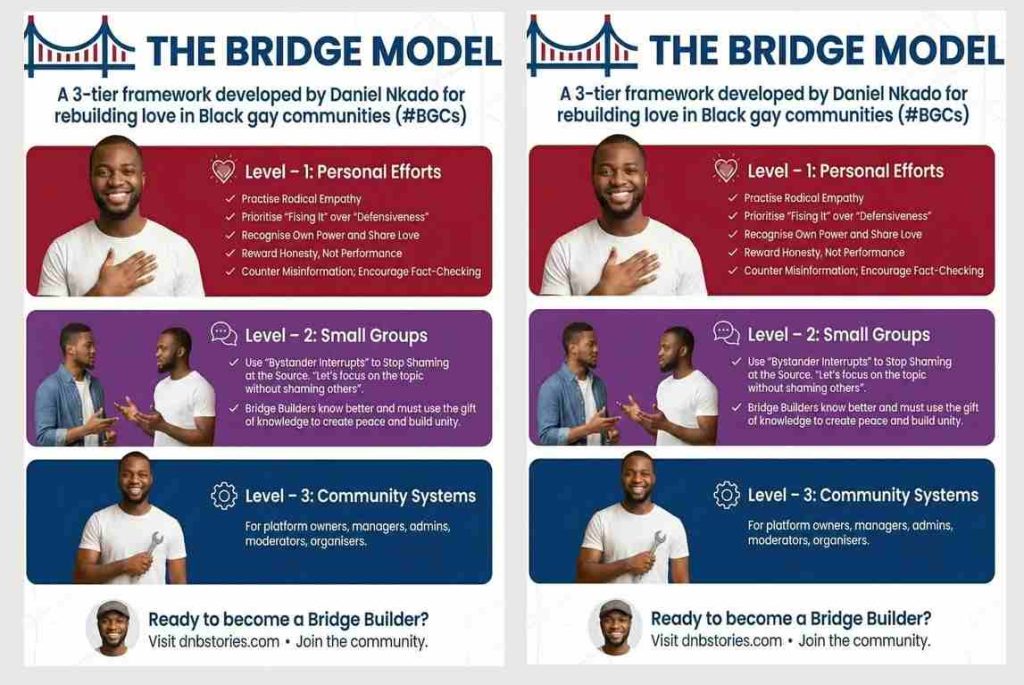

Bridge Builders and the Repair of Masculinity‑Driven Harm

Bridge builders play a vital role in repairing trust within Black gay spaces, particularly where masculine norms around silence, reputation, and indirect conflict have allowed harm, exclusion, or power imbalances to fracture community bonds.

According to the repair framework developed by Daniel Nkado, Bridge Builders are not neutral bystanders. They are people with lived experience of both harm and care, who understand how quickly conflict can escalate when direct confrontation feels unsafe or socially costly. They use their credibility to hold space for difficult conversations without turning disagreement into spectacle or exile.

Their role in this particular context includes:

- Facilitating dialogue between parties who may not feel safe speaking directly, especially in contexts where visibility carries risk.

- Naming harm without resorting to public shaming, which can trigger defensive masculinity rather than accountability.

- Modelling accountability and repair in environments where formal systems are absent, distrusted, or perceived as punitive.

- Helping communities distinguish between harm and conflict, and between accountability and punishment—clarifying what repair actually requires.

- Offering low‑stakes entry points for reflection, rather than demanding immediate public confessions or performative remorse.

Bridge builders are especially important in spaces where indirect conflict can spiral into social exile and where masculine avoidance of confrontation leaves few pathways for repair. By re‑centring care, clarity, and mutual protection, they offer alternatives to both silence and spectacle—making it possible to address harm without reproducing the very dynamics that caused it.

Coercive Control: Harm Minimisation Strategies for Black Gay Men

For Individuals

- Name the Harm, Not the Person: Learn to identify harmful behaviours—such as secrecy used for control, emotional withdrawal as punishment, or social exclusion as manipulation—without immediately labelling someone as “toxic.” Pattern recognition allows for clearer responses and reduces reactive escalation.

- Set and Revisit Boundaries: Be explicit about your emotional, social, and disclosure boundaries, and revisit them as relationships evolve. Resistance to boundaries—or punishment for asserting them—is a red flag.

- Document Your Experience Safely: Keep a private record of incidents that feel harmful, confusing, or destabilising. This helps track patterns over time and provides grounding if you later need support or validation.

- Build a Safety Net: Maintain at least one or two trusted connections where you can speak honestly. Isolation increases vulnerability to coercive dynamics; connection is protective.

- Resist Performing “Strength” Through Silence: Emotional suppression is not resilience. Allow yourself to name and process harm, even if you choose not to disclose it publicly.

- Know Your Exit Routes: If a relationship or network becomes unsafe, plan how to disengage with minimal fallout. This may include digital boundaries (blocking, muting, changing passwords) and social ones (shifting circles, limiting contact).

- Avoid Retaliatory Outing: It increases physical danger and ethical harm.

For Communities

- Create Low‑Stakes Accountability Spaces. Develop peer‑led spaces where people can discuss harm, missteps, and power without fear of public shaming or exile. This can include check‑in circles, moderated group chats, or anonymous feedback channels.

- Normalise Conflict Literacy. Share tools—workshops, zines, or dialogues—that help people recognise and respond to relational harm, especially covert control, emotional manipulation, and coercive secrecy.

- Challenge the Glamour of Control. Use storytelling, art, and public conversation to disrupt the idea that secrecy, emotional detachment, or dominance cues represent strength or Black masculinity. Reframe care, clarity, and accountability as forms of power.

- Support Emotional Expression Among Black Men. Create spaces—particularly for Black queer men—where emotional honesty is affirmed rather than penalised. This reduces reliance on indirect or controlling behaviours as default responses to conflict or insecurity.

- Develop Shared Language Around Power: Equip communities with accessible, culturally grounded language to discuss power, harm, and consent, without resorting to clinical or carceral frameworks.

- Protect Boundary‑Setters and Whistleblowers: Make it clear that those who name harm or set limits will be supported rather than punished. Silence often persists because social exile feels more dangerous than the harm itself.

- Design for Exit, Not Just Inclusion: Healthy communities allow people to step back, disengage, or leave without retaliation. Build norms that support graceful exits and returns, rather than treating distance as betrayal.

Getting Help in the UK

If you are experiencing coercive control, support is available:

- Galop: The UK’s LGBT+ anti-abuse charity.

- Switchboard LGBT+: A safe space to talk about anything.

- Men’s Advice Line: Support for men experiencing domestic abuse.

- NHS Domestic Abuse Guidance: Medical and psychological support pathways.

- Emergency: Call 999 (Emergency) or 101 (Non-emergency).

FAQs

“Mandem” is a term from Multicultural London English (MLE) meaning “men” collectively or a group of male friends. In many contexts, it is neutral (e.g., “me and the mandem”). However, in the context of this article, it refers to a specific performance of hypermasculinity associated with “road” culture: a code of behaviour that prioritises status, emotional containment, and a rigid definition of “respect.”

“DL” (short for “Down-Low”) is a term commonly used in Black gay communities to describe men who engage in same-sex intimacy while publicly presenting as heterosexual. While this form of concealment can serve as a necessary survival strategy in high-risk environments, its continued use in relatively safer contexts—where secrecy no longer serves a mutual purpose—can create power imbalances in relationships. In such cases, secrecy may be weaponised to maintain control, avoid accountability, or limit a partner’s autonomy.

No. The term itself is not automatically harmful, and for many, it represents brotherhood and loyalty. The concern arises only when this performance of masculinity becomes a tool for control—where “composure” is used to dismiss feelings, and “respect” becomes a pretext for covert intimidation or emotional punishment.

Coercive control refers to a pattern of behaviours—rather than a single incident—used to dominate, isolate, or destabilise another person. It can involve intimidation, threats, humiliation, monitoring, or other forms of psychological and emotional pressure. The aim is to make someone increasingly dependent by cutting them off from support, limiting their autonomy, exploiting their resources, and regulating their daily life.

Yes. In England and Wales, controlling or coercive behaviour in an intimate or family relationship is a criminal offence under Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015.

References

- Benebo, F. O., Schumann, B., & Vaezghasemi, M. (2018). Intimate partner violence against women in Nigeria: a multilevel study investigating the effect of women’s status and community norms. BMC Women’s Health, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0628-7

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Human Dignity Trust (HDT). (2013). Nigeria: Country Profile | Human Dignity Trust. Humandignitytrust.org. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/country-profile/nigeria/

- McCune, J. Q. (2014). Sexual Discretion: Black Masculinity and the Politics of Passing. The University Of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo17092702.html

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K., & Bränström, R. (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000271

- Serious Crime Act. (2015). Serious Crime Act 2015. Legislation.gov.uk. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/9/section/76

- University of York. (2025). What is MLE? – Department of Language and Linguistic Science, University of York. York.ac.uk. https://www.york.ac.uk/language-linguistic-science/research/projects/mle/what-is-mle/

- Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., & Weaver, J. R. (2008). Precarious Manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1325–1339. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0012453