1. Muscularity vs. Hypermasculinity—Why the Distinction Matters

For Black gay men, a muscular body often attracts assumptions—about sexual role, aggression, and even threat. And sometimes, too, macho labelling. While muscularity can come from sport, self-care, or personal style, some people read muscular Black gay men through the lens of hypermasculinity—a strategic performance of masculinity marked by dominance, emotional restraint, and policing others to mask personal insecurity or shame.

Neutral muscularity refers to a Black man’s muscular physique that results from sport, work, health, personal style, or genetics—and not as a signal of dominance, aggression, or status. This distinction matters because society often racialises muscular Black bodies as hypermasculine, turning ordinary physical traits into stereotypes that affect trust, policing, and social inclusion (Smiler, 2024)[4].

Misreading neutral muscularity as hypermasculinity invites fetishisation and assumptions about sexual role or aggression. This can pressure men to downplay or alter their bodies or force them into performances that may not reflect who they truly are.

This guide separates the body from the script: muscularity describes physical development shaped by genetics, health, work, or sport, while hypermasculinity describes a social performance of masculinity used to assert dominance, enforce status, or hide shame[7].

By distinguishing neutral muscularity from hypermasculinity, the guide challenges the false assumption that a muscular body—particularly a Black man’s body—automatically signals aggression or power seeking.

- 1. Muscularity vs. Hypermasculinity—Why the Distinction Matters

- 2. What Muscularity Is—and What It Isn’t

- 3. What Hypermasculinity Is—Masculinity as a Tool

- 4. Muscularity vs. Hypermasculinity: How to Tell—Without Profiling

- 5. The Repair Test for Hypermasculinity by DNB Stories

- 6. Why Hypermasculinity Polices Other Men

- 7. Mental Health and Community Impacts of Hypermasculinity

- 8. Solutions to Toxic Hypermasculinity in Black Gay Culture

- Conclusion

- References

2. What Muscularity Is—and What It Isn’t

Muscularity describes the physical outcome—greater muscle mass and definition—produced by training, physical labour, nutrition, and recovery. On its own, a muscular body does not reveal a man’s values, intimacy style, or relationship to status. It stands as a neutral physical trait, not a reliable signal of aggression, dominance, or sexual role.

Muscularity in Black gay men can reflect the pressures[1] of navigating body-coded queer spaces—where bodies often dictate access—but it does not automatically communicate a macho or hypermasculine identity.

Examples of Neutral Muscularity:

- An athlete training for performance.

- A construction or warehouse worker whose strength reflects daily labour.

- A gym‑goer focused on health or injury prevention.

- A dancer or martial artist who developed muscle through movement.

- A Black man with a naturally muscular build due to genetics.

- Someone who lifts weights for stress relief or longevity rather than as a motive to humiliate or police others.

3. What Hypermasculinity Is—Masculinity as a Tool

Hypermasculinity shows up in behaviour, not body type. It operates as a social script in which someone deliberately dials up common masculine traits like dominance, toughness, and emotional restriction—so intensely that they become hard to miss. He usually does this with a specific goal in mind—to gain power, increase desirability, or deflect attention from anything he fears will be read as feminine.

Because it is performed rather than innate, hypermasculinity can be adopted, maintained, or dropped depending on the context and the audience. To ensure safety, read it as a strategic social performance, not a reliable window into a person’s values or inner life.

Understanding How Hypermasculinity Shows Up—3 Signs

Psychology research defines hypermasculinity as a “macho” constellation of traits[3], consisting of three operational components:

a. Callous sexual attitudes toward partners — an endorsement of sexual conquest, objectification, and entitlement that treats intimacy as domination rather than mutual connection.

b. Violence as manhood — the belief that aggression, force, or the willingness to use violence are central to being a “real” man and the legitimate way to solve problems or gain respect.

c. Toughness and danger as exciting — an emphasis on physical strength, stoicism, and risk‑taking as markers of masculinity, and a readiness to present oneself as threatening or impervious to vulnerability.

Together, these three components form a behavioural script—often called The Macho Script— people perform to signal toughness, status, or sexual desirability.

How Hypermasculinity or Macho Performance Forms In Men

If a boy’s earliest experiences of softness, tenderness, or “feminine” expression attracted punishment, shaming, or mockery, he learns a simple rule:

Femininity in boys = danger.

To stay safe, he may try to overcompensate by intensifying the traits his shamers approve as manly. This is how the macho act is born.

Relationship Between Hypermasculinity, Shame and Fear

According to research, shame does not create hypermasculine behaviour from scratch. Rather, it triggers the masculine script a man already carries. When a man gets shamed for showing softness or expressing an emotion perceived as feminine, he doesn’t invent a new personality. He reverts to the “masculine norms” he has already been exposed to through culture, the media, and his peers (Vandello et al., 2008)[6].

The outcome largely depends on how strongly he holds these norms.

- When norms are weak, he might walk away or respond to the conflict with conversation.

- If norms are strong, he responds by dialling up his dominance and quickly joins in shaming and policing others. He’s assigned himself a false rank in the fantasy world of masculinity.

Masculinity in a State of Fear = Hypermasculinity

Hypermasculinity is a shame reflex disguised as dominance—where the fear of being seen as weak, feminine, or inadequate births a performance. Hypermasculinity is what masculinity looks like when it is panicking.

This distinction matters because it creates space for empathy. When a man becomes hyper‑aggressive or overly dominant, he’s usually not operating from power—he’s operating from shame. He’s in a high‑threat state, feeling exposed, deranked, or invalidated, and he reaches for the only armour he trusts will protect him—his masculinity. The performance isn’t proof of strength—it’s evidence of fear.

Hypermasculinity is a fear response, but this doesn’t make it harmless. When a man feels cornered, exposed, shamed or deranked, his nervous system shifts into survival mode. In that state, he’s not reasoning—he’s defending. And like any cornered animal, he may lash out. The safest move is distance, not debate.

The Macho Script vs. Personal Charm

Hypermasculinity is masculinity deployed to secure status, deflect attention from vulnerability or perceived femininity, and control the room. It depends on exaggerated displays of dominance, toughness, and emotional restraint to maintain power in a social space rather than foster connection. Unlike charm or grace, which draw attention through ease, warmth, and authenticity, hypermasculinity functions as a coercive performance that polices behaviour and conceals weakness.

Comparing performative toughness with authentic social confidence:

| Aspect | Macho Script (Hypermasculinity) | Personal Charm (Healthy Confidence) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A performed script that amplifies toughness, dominance, and emotional restraint to win status and hide fear. | A grounded, relational style that draws people in through warmth, attentiveness, and ease. |

| Core traits | Dominance signalling, emotional restriction, compulsive self-reliance, readiness to intimidate or “out-rank.” | Courtesy, emotional attunement, confidence without coercion, strong social intelligence. |

| Typical drivers | Threat management under stigma; peer policing; environments that reward hardness; media scripts that equate “manhood” with control. | Secure self-worth, practice in relational skills, empathy, and consistent experiences of safety and repair. |

| Primary goal | Secure status, deflect vulnerability, and control the social space. | Build trust, foster connection, and influence through rapport. |

| Social payoff | Fast credibility in dominance-valuing rooms; deterrence of challenge; “toughness” as social cover. | Deeper relationships, sustained influence, and higher emotional reciprocity over time. |

| Costs & limits | Courtesy, emotional attunement, confidence without coercion, and strong social intelligence. | Can read as “soft” in hierarchies that reward hardness, but it scales better and stays sustainable. |

| How it signals | Posture as threat display, aggressive speech, stoic affect, conquest or toughness storytelling, policing others’ expression. | Emotional isolation, surveillance anxiety, conflict-prone dynamics, and a greater risk of coercive patterns. |

Black Gay Men and the Macho Pressure

Black gay men frequently experience exclusion in dominant queer spaces—both online and physical—and in dating contexts, shaped by racialised stereotypes, sexual stigma, and community norms. This exclusion is amplified by the “Masc” culture on gay dating apps and social media, where tags like Masc for Masc and No Fems commodify Black masculinity and reduce gender expression to a marketable filter.

As a result, many Black men—particularly those without other alternatives to status—feel compelled to perform a rigid form of masculinity to avoid being filtered out and to secure attention, protection, or social standing.

4. Muscularity vs. Hypermasculinity: How to Tell—Without Profiling

When you meet a macho-presenting man, and you feel like you can’t see him beyond what he is deliberately showing you, that is usually the first sign.

You cannot diagnose motive from appearance. However, you can identify hypermasculinity by using these two signals:

a. Healthy Masculinity/Just Muscular:

A man with healthy masculinity—whether muscular or not—is flexible with his emotions rather than rigid. He does not intentionally block his feelings or treat vulnerability[5] as a threat to self‑respect. A man with healthy masculinity can express softness, uncertainty, or care without fearing a loss of status. He adapts to situations rather than trying to dominate them. This form of masculinity emphasises authenticity, emotional openness, and relational ease rather than performance or control (McDermott et al., 2019)[2].

b. Hypermasculinity as Performance

Hypermasculinity operates as a rigid, audience‑dependent performance. The macho man constantly scans for power, seeks to control the room, and leans into dominant narratives to secure status. He often shows contempt for softness—suppressing it privately in himself while policing it publicly in others. He treats emotional restraint as proof of strength. This performance relies on continual comparison and power‑measuring, turning masculinity into a tool for positioning himself as the authority in the room rather than a mode of authentic self‑expression.

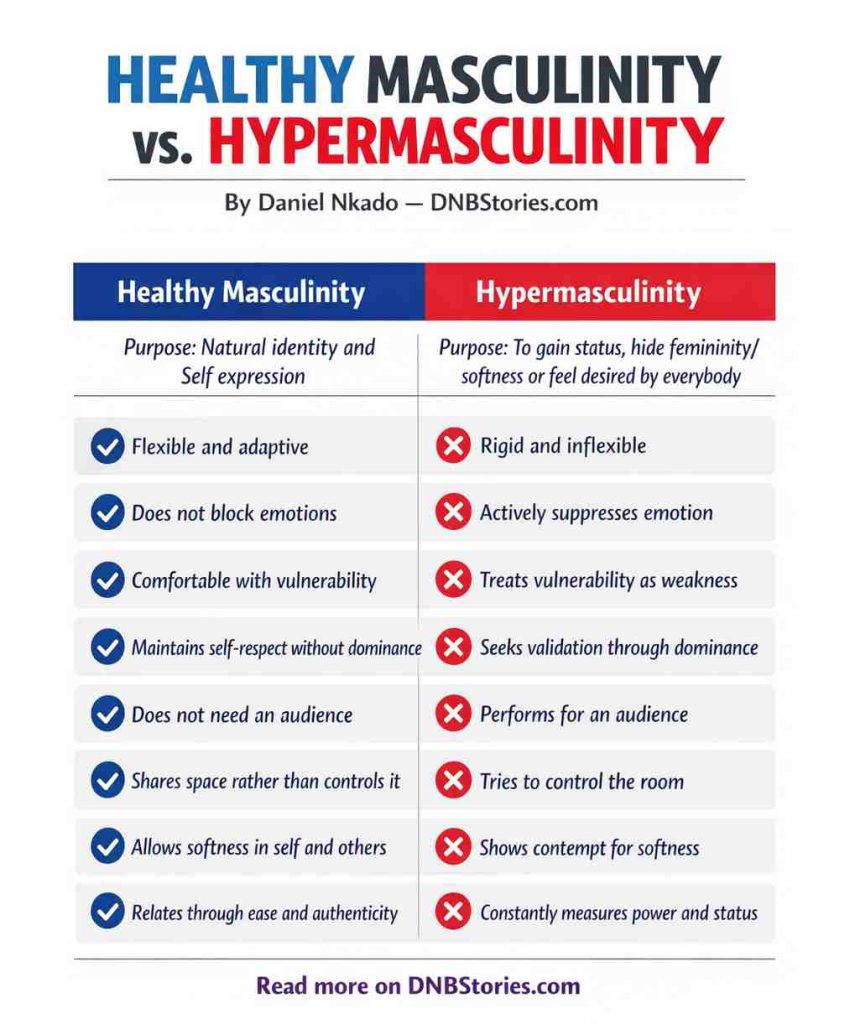

Healthy Masculinity vs. Hypermasculinity

| Healthy Masculinity | Hypermasculinity |

|---|---|

| Purpose: Natural identity and self‑expression | Purpose: To gain status, hide femininity or softness, or feel desired by everyone. |

| Flexible and adaptive | Rigid and inflexible |

| Does not block emotions | Actively suppresses emotion |

| Comfortable with vulnerability | Treats vulnerability as weakness |

| Maintains self‑respect without dominance | Seeks validation through dominance |

| Does not need an audience | Performs for an audience |

| Shares space rather than controlling it | Tries to control the room |

| Allows softness in self and others | Shows contempt for softness |

| Relates through ease and authenticity | Constantly measures power and status |

Key Indicators: Hypermasculinity in Black Gay Men

a. Anger Reflex

He defaults to anger, aggression, or contempt when his authority—or sense of dominance—is threatened. This response does not signal strength. It’s a defensive reflex. When authority is grounded in security, it doesn’t need to be defended. When it’s grounded in insecurity, even a mild challenge feels like an attack—so the nervous system escalates.

b. Credential Storytelling—Performative Proof of Hardness

Credential storytelling is a hypermasculine practice involving the use of narratives designed to prove toughness, dominance, or “hardness.” These stories often focus on violence, sexual conquest, or street credibility and typically escalate when the macho man’s authority feels threatened. The purpose of these stories, of which some may be cooked-up and deliberately twisted, is not reflection, but strategic deployment to assert dominance and prevent challenge within a masculine hierarchy. In sexual contexts, stories frame encounters as “trophies” to signal positioning rather than intimacy. Socially, they may reference proximity to danger or crime—such as prison talk—to project invulnerability and superiority.

c. Macho Branding

Hypermasculine performers use macho labels like “alpha,” “dom top,” or “masc only” to signal high status and dominance, often regardless of their actual feelings or reality. These labels work as a pre-packaged “masculinity kit” designed for quick recognition and to project power without requiring emotional depth or vulnerability. By maintaining distance from queerness, often by referencing heteronormative experiences—girlfriends, kids—they align themselves with heteronormative masculine power. This status performance also extends to clothing choice, voice, posture, and online presence, all curated to project hardness, control, and emotional inaccessibility.

5. The Repair Test for Hypermasculinity by DNB Stories

If you’re trying to tell whether a man’s behaviour comes from security or insecurity, watch how he handles repair. Healthy masculinity stays flexible—it bends. Hypermasculinity stays rigid—it breaks.

A practical checklist for healthy masculinity vs. hypermasculinity

This is not a clinical or psychological diagnostic tool. Use it as a practical lens for observing behaviour during conflict. When conflict happens, notice the response.

✅ Signs of Healthy Masculinity

- He admits fault without spiralling into defensiveness.

- He prioritises repair over being “right.”

- He can say, “I messed up. I’m sorry,” without treating apology as humiliation.

- He listens without interrupting, reframing, or escalating.

- Disagreement does not threaten his sense of self.

- Accountability strengthens the relationship rather than “reducing” him.

- You feel safe to breathe, disagree, and enforce boundaries around him.

🚩 Signs of Hypermasculinity

- He treats an apology as submission or loss of status.

- He will deflect, blame you—”I wouldn’t have yelled if you didn’t…”

- He minimises, dismisses, or gaslights your feelings.

- He escalates to anger, aggression, threats or shuts down to regain control.

- He treats mistakes as “cracks in the armour” that must be hidden.

- Control becomes more important than connection.

- You feel like you’re walking on eggshells when around him.

👍🏾Rule of thumb

✅If masculinity bends, it’s rooted in security.

⛔If masculinity breaks, it’s rooted in performance and fear.

6. Why Hypermasculinity Polices Other Men

When someone’s rise in status depends on a fabricated performance of masculinity, that performance remains under constant threat of exposure. To protect his act, the macho performer tries to assert himself as the gatekeeper of “real” masculinity, positioning himself as the confirmer of who qualifies as masculine and who doesn’t. This authority is unearned, and he does not bother to support it with evidence, theory, or reason. Instead, defaults straight to active enforcement.

To maintain status, the hypermasculine performer often relies on verbal shaming—jokes, slurs, or “banter” that label expressive men as weak, feminine, or “too gay.” Another tactic is enforcing sexual‑position hierarchies, rigidly claiming “top” status not from authentic desire but as a signal of dominance.

Men who hold status while remaining expressive pose a direct threat to this performance. In response, the hypermasculine performer may attempt to derank them through gossip, ridicule, or “conquest narratives” that frame others as inferior. These behaviours reflect insecurity and threat response—not confidence.

Example:

i. Hypermasculinity performance: “I topped him and made him moan like a b*tch.”

Focus: domination, humiliation, status.

ii. Healthy masculinity: “We had amazing sex, and I still feel fondness when I think about it.”

Focus: mutual pleasure, warmth, intimacy.

7. Mental Health and Community Impacts of Hypermasculinity

We explore the individual and community harms of hypermasculine performance in more detail in our previous article: Hypermasculinity—How Fear Drives The Macho Act.

8. Solutions to Toxic Hypermasculinity in Black Gay Culture

Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model is a three‑level trust‑repair framework that addresses community‑level harm across personal behaviour, peer norms, and community systems. When applied with intention, it weakens the social incentives that sustain hypermasculinity, shaming, and hierarchy, helping restore conditions for dignity, accountability, and care.

For a deeper discussion of how Daniel Nkado’s Bridge Model can be applied to disrupt cycles of hypermasculine harm in Black gay communities, refer to our previous article, Hypermasculinity in Black Gay Men.

Conclusion

The issue is not a Black man’s strength or muscles—these are not inherently harmful and can be admired. The problem is the rigidity of a performed masculinity that harms people who do not participate in it and ultimately wounds the performer, too. Healthier masculinity prioritises flexibility, intimacy, and repair over dominance and control. Hypermasculinity, by contrast, spreads harm by making shame structural, normalising policing at the community level, and framing humiliation as a masculine trait.

References

- Calzo, J. P., Corliss, H. L., Blood, E. A., Field, A. E., & Austin, S. B. (2013). Development of muscularity and weight concerns in heterosexual and sexual minority males. Health Psychology, 32(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028964

- McDermott, R. C., Pietrantonio, K. R., Browning, B. R., McKelvey, D. K., Jones, Z. K., Booth, N. R., & Sevig, T. D. (2019). In search of positive masculine role norms: Testing the positive psychology positive masculinity paradigm. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 20(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000160

- Mosher, D. L., & Sirkin, M. (1984). Measuring a macho personality constellation. Journal of Research in Personality, 18(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(84)90026-6

- Neilson, E. C., Singh, R. S., Harper, K. L., & Teng, E. J. (2020). Traditional masculinity ideology, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity, and treatment in service members and veterans: A systematic review. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000257

- Smiler, A. P. (2024). Understanding masculinity: A multifaceted organizing framework. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 25(4), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000495

- Sullivan, L., Camic, P. M., & Brown, J. S. L. (2015). Masculinity, alexithymia, and fear of intimacy as predictors of UK men’s attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12089

- Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., & Weaver, J. R. (2008). Precarious Manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1325–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012453

- Way, N., Cressen, J., Bodian, S., Preston, J., Nelson, J., & Hughes, D. (2014). “It might be nice to be a girl… Then you wouldn’t have to be emotionless”: Boys’ resistance to norms of masculinity during adolescence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037262