‘Hood’ Stereotype in Black Gay Culture

While other definitions exist, in queer discourse and LGBTQ+ digital spaces, the term “hood” takes on a specific, troubling meaning. “Hood” in gay culture refers to a “street guy” or “thug” stereotype projected onto Black gay men, tied to aggression, lack of education, and criminality.

This projection carries a damaging triple threat: it sexualises, racialises, and classifies Black life, collapsing complex individuals into a fetishised caricature of hyper‑masculinity and dominance (Stuart & Benezra, 2017)[8].

To fully understand the harm embedded in this word, we must first trace its history in Black gay culture.

Toxic Masculinity and the Racist History of ‘Hood’

The “hood guy” archetype in Black gay culture is a product of deep-seated racist history. Dating back to slavery, Black men were cast as physically strong, ruggedly masculine labourers whose value lay in their bodies rather than their minds—the “strong bodies, diminished minds” narrative.

Scholars often link the “hood guy” stereotype to the plantation Buck caricature—a racist trope portraying Black men as hyper-masculine, violent, and sexually threatening (Majors & Billson, 1993)[4].

White supremacists used the Black Buck stereotype—along with others like “Brute,” “mammy,” and “Uncle Tom”—to maintain racial hierarchy and justify violence and the lynching of Black men.

Hood Masculinity in Black Gay Relationships

Many Black gay men who adopt “hood” or “DL” personas may be unaware of the historical link to slavery or have succumbed to the pressure to conform.

The demand for “straight-acting” qualities (DL, Rugged, Traditional Fresh) has turned the “hood” aesthetic into a form of erotic capital or sexual currency. Men who perform this persona well—deep voice, guardedness, muscular build, and refusal of softness—remain highly desired. Their perceived “hardness” is often seen as authentic Black masculinity, a false belief rooted in slavery-era auction blocks where Black men were forced to display physical strength while prioritising obedience to their masters (Green, 2013[2]; Strayhorn & Tillman-Kelly, 2013)[7].

Hyper-Masculinity as Status and Safety Mechanism

White slave masters reinforced these ideas through divide-and-conquer tactics, appointing physically imposing enslaved men as overseers. Because literacy was criminalised and physical strength was prized, many enslaved men learned to equate worth with toughness and endurance (Hooks, 2004)[3].

Slavery created a system that didn’t just reward toughness but made it synonymous with survival. Over time, what began as protection hardened into a status code.

This legacy continues to shape modern Black masculinity, where aggression and other signals of hyper-masculinity carry more value than intellect.

Link Between Slavery-era Sexual Violence and Emotional Hardness

Enslaved Black men were subjected to sexual violence as a tool of control and domination. Most victims processed their trauma quietly and alone. Over time, this silence hardened into emotional suppression, giving rise to a new survival strategy.(Foster, 2011[1]; Stuart & Benezra, 2018)[8].

Similarly, the DL identity evolved under comparable pressures, though its trajectory tells a different story.

Harms of Performing ‘Hood’ in Black Gay Culture

The prioritisation of physical dominance over intellect was a tool of control used during slavery. Its legacy continues to shape perceptions of masculinity and desirability in Black gay communities today.

Harms of “Hood” personas:

- Performance Over Authenticity: The idealisation of “hood guys” forces many Black gay men to discard intellect and perform the persona. This creates a pattern that mirrors the historical exploitation of slavery.

- Encourages Risky Behaviour: It promotes fear-based behaviours as a way of proving or defending a masculine image.

- Policing Others: Crucially, this racial caricature is internalised, leading Black gay men to police one another with it. Hyper-masculinity is rewarded, while anything perceived as soft is punished.

- Minimises Black Intellect: The high currency of racialised masculinity in Black gay culture turns it into a marker of status. This makes it harder to champion or push for Black intellectualism.

- Intensifies Anti-Blackness: Prioritising aggressive, macho traits as “authentic” Black masculinity creates a false narrative that academic and career success are anti-Black.

- Widens Community Division: Stereotypes like this echo the divide-and-conquer tactics used during slavery to create harmful hierarchies that fracture communities.

DL (Down-Low) Culture: Then and Now—From Survival to Status

“DL” (Down-Low) originally described men—often Black or Latino—who publicly presented as straight while privately engaging in same-sex relationships. The code emerged in African American slang in the late 1990s as a survival strategy against homophobia and rigid social norms. Secrecy wasn’t a trend back then; it was protection. In hostile environments, men still go DL for safety. Sometimes, this involved dating or marrying women as a cover against violence or stigma.

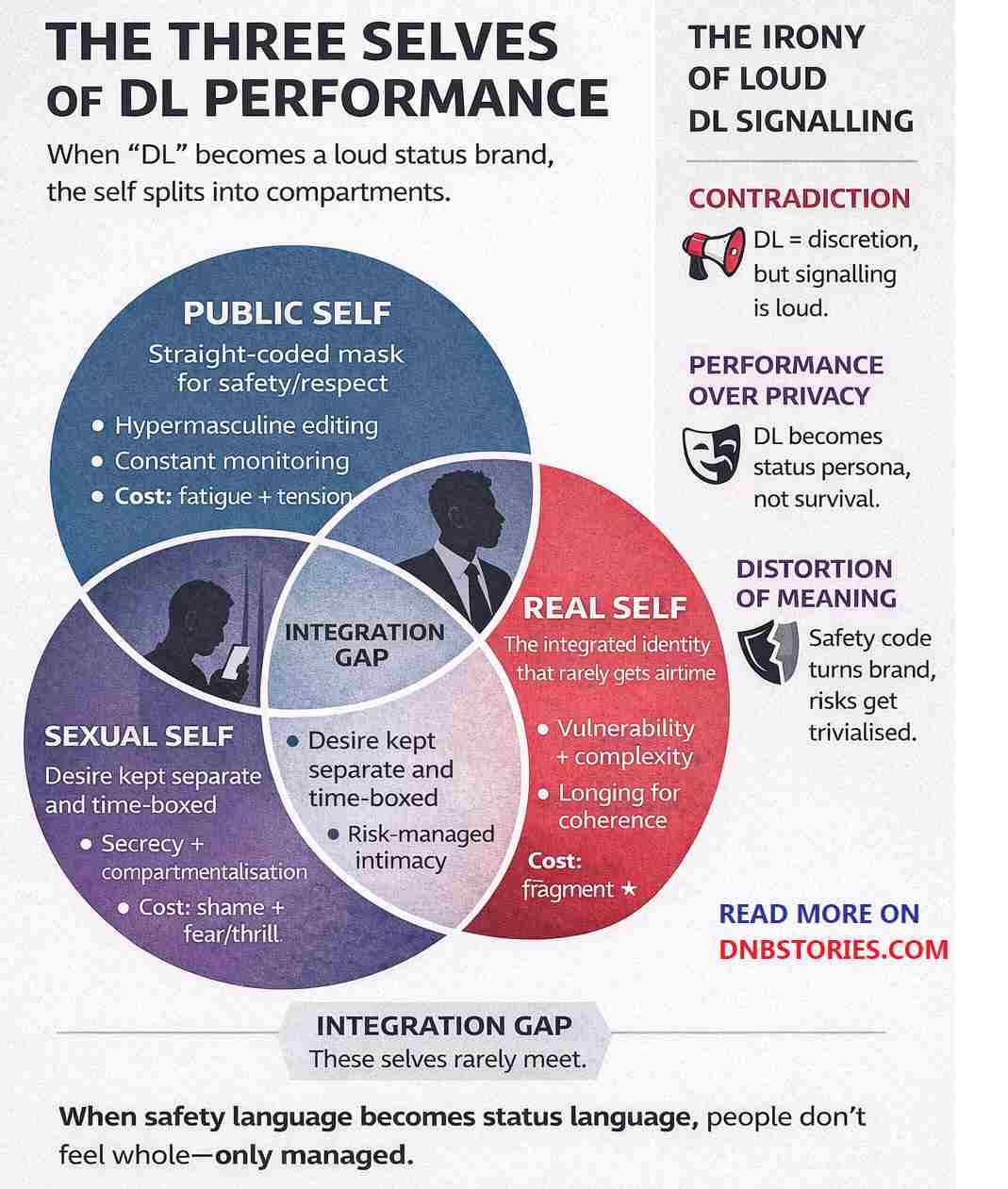

a. Western DL Culture Today: Performance and Branding

In Western contexts, “DL” has shifted from a survival code to a commodified online persona. Once a shield for safety, it now signals a stylised, taboo masculinity on apps and in porn, turning secrecy into erotic capital and creating hierarchies that reward performative discretion.

“DL posing”—using the DL label for status—erases its cultural roots and reframes stigma as desirable. This trend ignores the reality of gay men in high-risk environments, where discretion remains a vital strategy for survival (Snorton, 2014)[5].

b. How DL Posers Gain Status on Apps

- Masculinity Branding: Using “DL” alongside tags like masc, dom, or trade to signal toughness and exclusivity.

- Erotic Capital: Leveraging the manufactured allure of secrecy and mystery—often without realising the attention is for the aesthetic, not the actual person.

- Proximity to Heterosexuality: Crafting bios with phrases like “DL Black Top” or “Married DL Guy” to attract those seeking “straight-acting/passing” aesthetics.

- Visual Cues: Posting photos with coded signals—hood aesthetics, tracksuits, face coverings, and urban styling—to project the DL persona.

- False Hierarchies: Men who are openly gay in practice often use the DL label to appear rare and inaccessible, creating an illusion of scarcity that boosts their desirability.

- Community Policing: Criticising openness or femininity in others to elevate their own “authentic” masculinity.

c. Harms of Curated DL Identities on Dating Apps

This section addresses the curated performance of DL identities for attention and status on dating apps (e.g., DL posing on Grindr). It intentionally excludes the experiences of LGBTQ+ people in hostile countries with a genuine survival need for secrecy.

Dangers of DL performances (posing) on gay apps:

- Erodes Trust: Commodifying secrecy creates a “trust deficit,” making individuals appear less reliable or moral in real life.

- Reinforces Stigma: Performing secrecy for status reinforces the idea that queerness is shameful and shouldn’t be openly embraced.

- Promotes Harmful Hierarchies: Elevates secrecy and hyper-masculinity as superior, marginalising those who are open and authentic.

- Normalises Risky Disclosure: Loud DL signalling can blur the meaning and “weight” of the term and increase exposure risks for genuinely closeted men in hostile environments.

- Encourages Fetishisation: The DL poser tries to profit from the manufactured allure of secrecy and taboo, but in doing so, reinforces the reduction of Black men to a sexual aesthetic and fetish fantasy.

- Psychological Strain: Performing DL for desirability can lead to internal conflict, anxiety, and identity fragmentation.

- Community Division: Creates illusory hierarchies that fracture solidarity and weaken collective empowerment.

Hood and DL Masculinity: The Dominant Top Trap

Hood and DL identities impose sexual role expectations—casting Black gay men as dominant “tops” and framing any deviation as weakness. This script looks like a modern remix of the same slavery-era narrative that valued only the bodies of Black men, discarding their intellect and depth.

Just as enslaved men were once conditioned to measure their worth through physical displays of masculinity, today that same narrative resurfaces on platforms like Grindr, where profile bios proudly advertise labels such as “dominant Black top”, “DL Top”, or “aggressive thug”. There is almost zero interest in markers that signal intellect or curiosity.

Black Gay Men: Rejecting Inherited Masculinity Scripts

Agency begins with awareness. When you recognise that a gender and sexual expectation was handed to you, not chosen by you, its power begins to weaken.

- Reclaim Softness as Strength: Softness is not a weakness; it is wisdom. Allowing oneself to be vulnerable or intellectually curious disrupts the machinery that polices harmful Black behaviour.

- Separate Desire From Expectation: Genuine sexual autonomy requires an honest exploration of one’s own pleasure, separate from any perceived need to perform or play a fantasy.

- Build Communities That Don’t Reward Performance: Create friendships, chosen family and spaces where intellect and vulnerability are valued, rather than spaces that demand “hardness” for entry.

- Reject the Fetishisation: Don’t let stereotypes dictate your desirability. Reject the “dominant Black top” role imposed on you by society—it’s a scam, like a king without a palace.

- Allow Multiplicity: Black men embody many identities. True freedom comes from embracing range and rejecting rigid roles.

Final Word: We Must Write Our Own Scripts

True liberation lies in forging our own paths through self-understanding, allowing masculinity to reflect our authentic selves rather than imposed expectations. This is the essence of self-defined masculinity. Our perspective on masculinity should be expansive enough to give every Black man the space to explore, question, and evolve without fear of judgment or limitation.

References

- Foster, T. A. (2011). The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 20(3), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1353/sex.2011.0059

- Green, A. I. (2013). “Erotic capital” and the power of desirability: Why “honey money” is a bad collective strategy for remedying gender inequality. Sexualities, 16(1-2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460712471109

- Hooks, B. (2004). We Real Cool. Routledge.

- Majors, R., & Billson, B. (1993). Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America. Touchstone Books/Simon & Schuster. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-97721-000

- Snorton, C. R. (2014). Nobody Is Supposed to Know. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816677979/nobody-is-supposed-to-know/

- Stacey, L., & Forbes, T. D. (2021). Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialised Feelings, Fetishisation, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Gay Dating Apps. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1979455

- Strayhorn, T. L., & Tillman-Kelly, D. L. (2013). Queering Masculinity: Manhood and Black Gay Men in College. Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men, 1(2), 83–110. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/503123

- Stuart, F., & Benezra, A. (2017). Criminalised Masculinities: How Policing Shapes the Construction of Gender and Sexuality in Poor Black Communities. Social Problems, 65(2), 174–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spx017