Love Story, But Stigma Said No

Taylor Swift and I are almost the same age. Sometimes, it feels like we grew up together—just not in the same place, and certainly not under the same rules.

While she sang her way through teenage romance on the world’s biggest stages, I was a teenager in Nigeria, learning early that certain kinds of emotions came with danger. Those years denied me the gentle initiation into desire that so many teenagers take for granted—the quiet experiments with tenderness, the awkward sweetness of being seen. All of it was out of reach. Openly dating was never a door I was allowed to walk through, let alone sing openly about.

I watched my crushes from a distance. Not like there were many of them, but I walked faster whenever the neighbourhood boy called my name. In the evenings, I helped him with his assignments. He would lean in, listening more closely to me than he ever did to the teachers in class. I would shift away, as if his touch made me uneasy. I hoped he didn’t truly believe that it did.

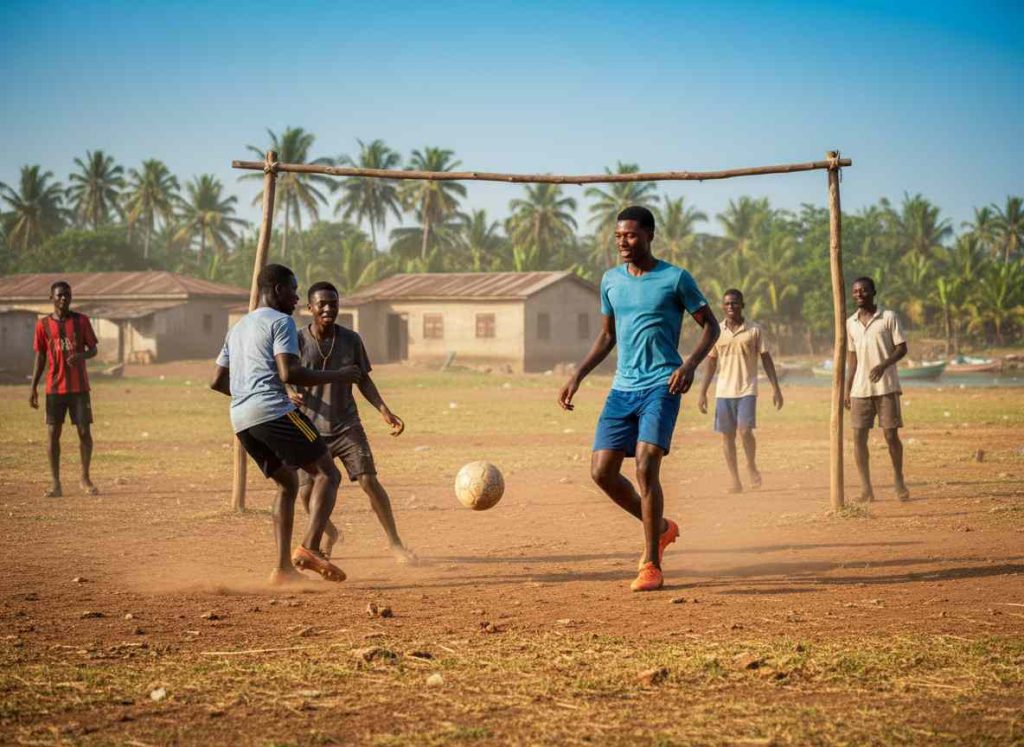

When we played football, and he picked me for his team—so he could jump on me when he scored—I kept the celebratory hugs brief. I blamed sweat, rehearsing a discomfort I didn’t feel.

Out in the Woods, Alone

Long before the Same‑Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act was signed into law in 2014, queer life in Nigeria already crawled beneath a low, mysterious cloud—watched, whispered about, carefully avoided[6]. The stigma was so heavy that being called “homo” in public could feel like your heart had missed a step. And the shadow only deepened with time, made thicker by each shop-counter gossip, Sunday sermons from Pastor Ezekiel, and the moral lessons that flickered across Nollywood screens at night. Peace was nowhere near the quiet gay boy’s heart to hold.

The first time I saw a gay character in a Nollywood film, he was a messenger of Satan, sent to collect souls on earth. When that is the script you inherit at such an age, you don’t just fear other people’s judgment. You begin to fear what you might truly be. What should have been a normal adolescence became something else entirely—not a rite of passage, but a constant reassessment of identity, of being, of the very air around you—whether you might stain it for others.

Nigeria, I Knew You Were Trouble

Adolescence is meant to be formative: a time of rapid psychosocial growth, emotional learning, and romantic experimentation. The World Health Organisation defines it as ages 10–19—an intensive period for laying the foundations of wellbeing, identity, and relationships[7]. But when you grow up knowing that being “found out” carries real consequences, that inner work doesn’t disappear. It relocates. And unfolds in coded corners, in half‑formed moments, in the privacy of a trembling imagination. It arrives in fragments rather than full arcs, confusion rather than clarity: a coming‑of‑age experience stitched together in the shadows.

For many queer people, especially in hostile contexts, desire isn’t simply a feeling. It becomes a weight you learn to carry without letting it show. What should be simple tenderness turns into Engineering Mathematics—full of variables, coded formulas, and the constant fear of getting the equation wrong.

Hard To Shake Off

I learned the language for this later. Researchers describe something called “minority stress” as the added psychological load queer people carry, produced by stigma, prejudice, and discrimination—an ongoing pressure that can shape mental health and everyday functioning over time (Meyer, 2003)[3]. Back then, I didn’t know Dr Meyer. I couldn’t have. The internet was expensive, too.

In this context, concealment is not just necessary for survival. It is survival. But while concealment can reduce direct exposure to harm, it leaves its own mark. Some researchers have found a small but consistent link between hiding who you are and psychological discomfort (Pachankis et al., 2020)[4].

So I found another way to grow up.

Filling Up My Blank Space—With Music!

Taylor Swift’s early songs became a rehearsal space for the emotional life I wasn’t allowed to have. They gave me vocabulary—and, more than that, permission—for experiences I couldn’t yet live in my own body.

There’s research to support why this works. Adolescents commonly use music for mood regulation and emotional processing, especially when the outside world is demanding or restrictive (Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007)[5]. Another study explained how relationships with media figures—what they call parasocial relationships—can serve as low‑risk arenas for identity formation and autonomy, particularly in early adolescence (Gleason et al., 2017)[1]. In other words, when the world feels unsafe, imagination finds safer places to practice becoming. Back then, I didn’t know any of this. I just knew the songs made room for me.

In this sense, my relationship with Swift’s music wasn’t “obsession” so much as adaptation. I borrowed the rites of passage, stepped into the narratives and tried on emotions in a world that might punish me for practising them out loud. I loved other singers too—Beyoncé, Jennifer Lopez, Lady Gaga—and later found new confidence in their work. But where these artists felt like superhero icons I could only imitate, Taylor Swift sang with a kind of emotional plainness that felt reachable. Her words sounded familiar enough that they could have been mine.

The songs that taught me what I couldn’t learn safely

- “Love Story” (released 15 September 2008) gave me my first fairytale teenage romance—the radical idea that wanting something could be met with joy rather than consequence.

- “White Horse” (released to US country radio on 8 December 2008) taught me disappointment: the slow unravelling of hope when promises don’t hold.

- “You Belong With Me” (released 20 April 2009) taught me longing—the ache of wanting to be seen as an option, not a secret, and the quiet belief that affection could be mutual rather than one‑sided.

- “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” (2012) offered a decisive ending. It wasn’t just a lyric; it was a boundary I didn’t yet know how to draw in real life.

- “Begin Again” (2012) taught me repair: the possibility that after disappointment and endings, something softer could still follow—careful, tentative, and earned.

Some of those moments stayed safely fictional. Others didn’t.

“Long Live,” the hostel door, and the defiance of feeling

I cared about someone once—someone real. Not imagined. It never became “anything” official, but the feeling was true and mutual. One night, we stayed up until morning singing “Long Live” at the top of our lungs, as if volume alone could consecrate the feeling—as if belief might harden into destiny if we sang loudly enough. That song wasn’t about certainty so much as defiance: a refusal to let meaning evaporate simply because the future was unclear.

Why should we stop wanting simply because the future is uncertain? And even if dreams weren’t realised, was it not enough that we dreamed them? Some dreams don’t come true. That doesn’t mean they didn’t matter.

A hard knock hammered the hostel door—probably the pious boy, Emmanuel, whose bed was closest to the entrance. On days he wasn’t praying, he liked to sleep. We went silent instantly, pretending to be asleep. We didn’t care that we’d been interrupted; we cared that we’d been heard.

That detail matters to me—not because it was “reckless,” but because it captures a reality many queer youths learn early in hostile settings. Even when care becomes contraband, and affection comes with fear, you still find ways to smuggle them in. It’s just who we are. The love of the world, I think—however small—goes back into making more queer people. Those small acts of defiance can feel like the difference between being alive and merely existing.

When he hurt me deeply by dying, I cried and cried and hated him. I didn’t understand why he had to be so cruel. He couldn’t even wait until “Blank Space” came out. He missed the whole beautiful music video. But eventually, I forgave him. I couldn’t not have.

You’re On Your Own, Kid—Always Have Been

There were other hard lessons, too—times when I trusted someone and that trust broke, cleanly and all at once. I let the grief take whatever shape it needed, even when it was tedious, ugly, or unproductive by every external metric. Somewhere in the middle of it, I learned that breaking was human—and that sadness and joy could live in the same life without cancelling each other out.

Loss taught me the importance of going through it: of feeling without shame or fear, of not blocking, suppressing, or avoiding what hurt. When it was over, it was truly over. And the next time, it wouldn’t cut as deeply. Suppressed emotions find other routes, and it frightened me to imagine what an unprocessed feeling might turn me into.

So now, crying doesn’t scare me. I trust that I will still be myself afterwards. I once read about the phoenix, rising from the ashes into glory. Sometimes, I felt like that was what I had become. This magical bird.

Months later, when the weight was finally lifted, I spent an entire week blasting “I Forgot That You Existed” like a private graduation ceremony. Forgetting, I learned, can be an achievement. Distance can be earned.

Outgrowing The Fairytale Without Calling It A Lie

What I miss most from those years isn’t the music itself. It’s the dreaming that came with it—the quiet belief that everything works out in the end, and that even when things fall apart, people can always find their way back to each other. Like adulthood—and like Taylor Swift’s later work—life eventually taught me otherwise. Love doesn’t always redeem. Closure isn’t guaranteed. Some endings remain unfinished simply because they’re over.

And yet, those years mattered. Daydreaming was a survival skill. Imagination wasn’t indulgence; it was shelter. Music became an enclosure where my heart could practise what I wasn’t permitted to do out loud. It gave me the emotional grammar of love long before I was allowed to speak it freely.

Stories—My Sweet Nothings

Stories hold such power for a reason: we don’t merely remember our lives—we shape them into meaning. We organise our experiences into scenes, turning points, and lessons, gradually crafting a narrative that becomes central to our identity.

McAdams (2001)[2] captured this insight well. His research shows that people begin constructing these life stories in adolescence and early adulthood to understand who they are, where they’ve been, and where they’re headed. These narratives offer a sense of coherence, purpose, and meaning—particularly in modern societies. Individuals with more mature thinking, or higher “ego development”, tend to tell richer, more reflective stories that reveal how they’ve grown or learned through adversity.

I didn’t lose those lessons when I outgrew the fairytale. They didn’t disappear; they refined themselves. I learned that softness doesn’t require illusion to survive. That hope can be quieter and still be real. That something doesn’t have to last forever to have been worth believing in. And—most importantly—that we grow by engaging, not avoiding: by taking the moment, however imperfect, and making it ours.

The fairytale didn’t lie to me. It did its job. It carried me to a version of myself who could finally let go of it without bitterness—only gratitude, and a little ache.

Not happily ever after.

But honestly, deliberately lived.

References

- Gleason, T. R., Theran, S. A., & Newberg, E. M. (2017). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships in Early Adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(255). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

- McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 100–122. https://www.self-definingmemories.com/McAdams_Life_Stories_2001.pdf

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Pachankis, J. E., Mahon, C. P., Jackson, S. D., Fetzner, B. K., & Bränström, R. (2020). Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(10), 831–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000271

- Saarikallio, S., & Erkkilä, J. (2007). The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607068889

- Schwartz, S. R., Nowak, R. G., Orazulike, I., Keshinro, B., Ake, J., Kennedy, S., Njoku, O., Blattner, W. A., Charurat, M. E., & Baral, S. D. (2015). The immediate effect of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. The Lancet HIV, 2(7), e299–e306. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(15)00078-8

- WHO. (2019, November 26). Adolescent health. Who.int; World Health Organisation: WHO. https://who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health

One More Time…