By Daniel Nkado.

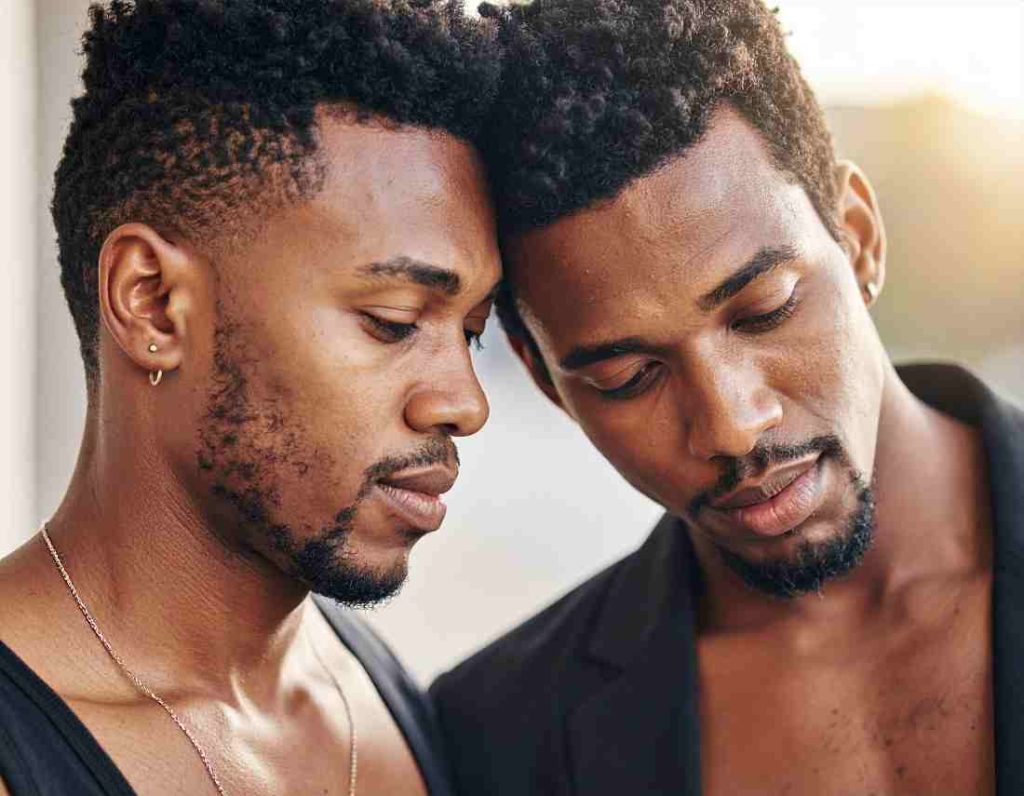

Gay men and the concept of defensive masculinity

Many gay men learn early in life through teasing and societal pressure that being “feminine” invites shame. So they respond to this stigma attached to femininity by engaging in compensatory behaviour— embracing and performing hyper-masculinity— to protect themselves from ridicule.

Over time, this creates a pattern elevating hypermasculine behaviour to a higher pedestal of acceptance and admiration.

“Straight-Acting”: This gave rise to the term “straight-acting” as the highest form of compliment among gay men in decades past (now replaced by its even higher forms—macho, dom, rugged).

Role of culture in masculine presentation among gay men

This dynamic plays out differently across cultures. For example, in some African, Black or Latino communities, the pressure to perform hyper-masculinity (go macho) may be compounded by racial stereotypes and cultural expectations of manhood, adding an extra layer of complexity to the “performance.”

Generational Shifts: Gen Z and younger Millennials are increasingly deconstructing this binary, embracing gender fluidity and “femme” presentation more openly than previous generations, suggesting the “pedestal” may be slowly eroding.

Not all gay men are performing masculinity!

Not all masculine gay men are performing or compensating. Many men (gay, bi or straight) are naturally masculine in their demeanour and interests without it being a defensive mechanism. This is called authentic masculinity, and it is often a softer shade of masculine behaviour, as later discussed in detail in this article.

Gay men prefer masculine behaviour or a good performance of it!

Studies show that many gay men prefer masculine-presenting or masculine-compensating partners, a situation that is often a reflection of deep-seated internalised homophobia (Gerrard et al., 2023)3.

Both in gay dating and regular community life, phrases like “masc4masc” or “no fems” remain common, reinforcing the rejection and exclusion of effeminate men.

However, the obsession among some gay men with masculine conformity bears an interesting irony—by idolising hyper-masculinity, the gay community inadvertently upholds the very patriarchal standards that marginalised them in the first place (Fischgrund et al., 2011)1.

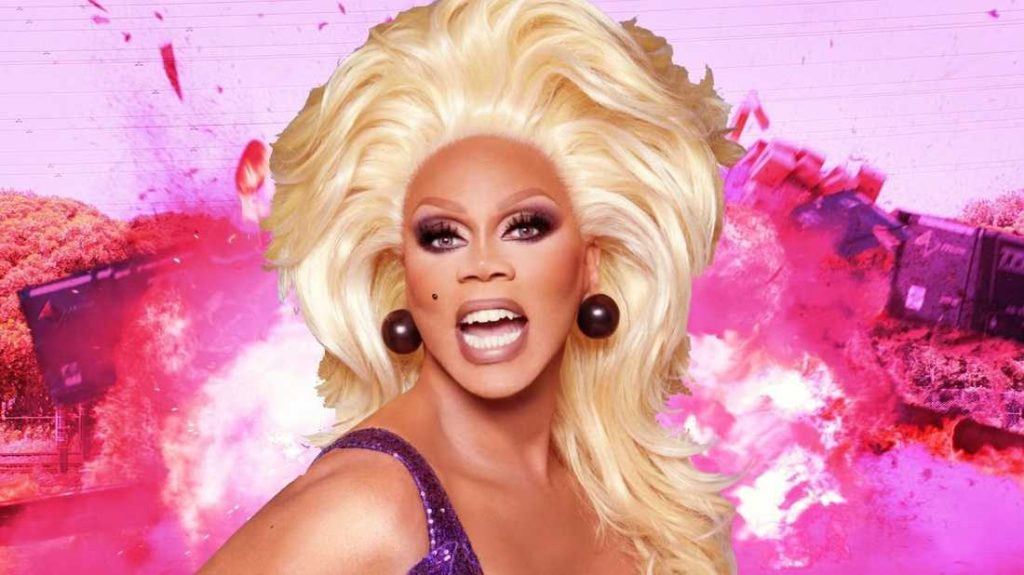

Gay men and the performance of masculinity

Some gay men born with strong feminine traits learn early that softness can attract judgment, so they decide to “switch”. Like a drag queen perfecting her drag, they refine their masculine act until any internal feminine tendencies are fully suppressed. It’s less about pretending — and more about surviving in a world that still fears difference.

Gay men often switch to masculine behaviour in response to different pressures and personal motivations, such as:

- To avoid stigma and discrimination

- For safety and survival, eg, gay men living in places where being gay is dangerous.

- Increase desirability and social acceptance, etc.

Hyper-masculinity or ‘macho behaviour’ in gay men

Research, such as that by Sánchez et al. (2012)5, suggests that gay men whose inborn disposition strongly leans toward effeminacy tend to overperform masculinity as a cover-up, as seen in some macho men.

This behaviour is called hypermasculine compensation or masculine overcompensation—or simply compensatory masculinity. It defines the exaggerated masculine behaviour adopted by some gay men to hide more pronounced feminine traits to avoid stigma and “pass” as heterosexual. Or at least pass as “straight-acting” gay men.

Also, by adopting a hyper-masculine identity, a gay man can signal to potential partners and peers that he is not the stereotype of the “camp” or “effeminate” gay man, which is often culturally devalued and associated with lower social currency within the community.

Some social writers have noted that gay men, especially those with stronger feminine tendencies, are more likely to exaggerate masculine behaviour (go macho) if they feel their masculinity is constantly being threatened or questioned, or they have previously been accused of being gay (Frost & Meyer, 2009)2.

Because hypermasculine or “macho” behaviour is highly prized in the gay social world, from dating apps to social media spaces, a well-executed hypermasculine behaviour rewards the performer by maximising his desirability in dating and earning him immediate social validation.

Common examples of compensatory masculinity or hypermasculinity in gay men may include a rigid adherence to masculine clothing, loudness, overemphasis on physical strength, and the explicit (and often arrogant) rejection of ‘femme’ traits.

Why gay men worship ‘masc4masc’ and the macho ideal

The preference for hyper-masculine, macho or “masc4masc” partners sometimes goes beyond genuine desire and can be a strategy to manage societal pressures and internalised prejudices (Herek et al., 2009)4.

The desire and pursuit of macho behaviour stands boldly as a message confirming and communicating the gay individual’s utter rejection of anything feminine, unknowingly reinforcing an unnecessary shame-invented hierarchy (“I’m not like those gay men”).

Authentic masculinity in gay men

It’s important to note that not all masculine gay men are performing or compensating; many embody a naturally masculine temperament. The distinction lies in intent—authentic masculinity flows effortlessly, while performative masculinity is driven by the need to prove.

Gay men with authentic masculinity usually embody a quiet confidence that contrasts sharply with the overperformed version seen in some hyper-masculine actors who may be trying to hide their feminine traits. Because this masculinity is genuine, there is no need to exaggerate or inflate behaviour.

Interestingly, this group often includes the quiet gays (gay men who present with calm masculinity and live their lives avoiding unnecessary attention) and some gay men who intentionally adopt an androgynous aesthetic.

Other reasons gay men go for macho

The preference for masculine partners can be complex and not solely rooted in stigma or femophobia. Factors like physical safety in hostile environments, genuine erotic attraction to masculine traits, and the pursuit of social compatibility can also legitimately shape partner choice (Frost & Meyer, 2009)2. Recognising these nuances helps distinguish between personal preference and structural exclusion.

Fem gay men — Champions of authenticity!

By rejecting gender norms to embrace one’s natural feminine tendencies, fem gay men offer a powerful representation of being true to oneself.

Yet, this authenticity comes at a cost. Fem gay men often face discrimination from both mainstream society and within the gay community as well, leading to potential psychological distress or social isolation.

What is Femophobia?

Femophobia—sometimes called anti-effeminacy bias—refers to the discomfort or disdain toward feminine traits in men. It’s often an internalised feeling, showing up as:

- Avoidance of flamboyant or expressive behaviour.

- Preference for “straight-acting” partners.

- Feeling shame around softness, vulnerability, or emotional openness

This fear is rooted in hegemonic masculinity—a cultural ideal that values dominance, stoicism, and heterosexuality. Gay men, growing up in these systems, often absorb the message: to be accepted, you must reject what makes you different. Femophobia often leads to the adoption and celebration of macho posturing — exaggerated masculine behaviour in many gay men.

Global and Cultural Nuances

Femophobia manifests differently across cultures, and understanding these layers is key to building inclusive queer spaces.

- In Western contexts, it’s often tied to media representation and dating app algorithms.

- In African and Caribbean communities, it may be reinforced by religious conservatism and colonial gender norms.

- Among Black gay men, masculinity can be both a shield and a prison—used to navigate racism, homophobia, and hypervisibility.

The Irony — Fem doesn’t like to date fem, either!

On dating apps, phrases like “masc only” or “no femmes” are widespread, signalling reduced desirability for feminine-presenting men in dating and social circles. Research consistently shows that feminine-presenting gay men face marginalisation, prejudice, and a higher rate of rejection in the gay dating market.

But what makes the entire situation a little ironic is that studies and anecdotal evidence have shown that a substantial number of feminine-presenting gay men are primarily or exclusively attracted to masculine men. This preference is so common that “fem4fem” is not nearly as prominent as “masc4masc” in the broader dating economy, though it does exist in some niche communities.

Some fem gay men have also openly noted a preference for “macho men” when it comes to dating. It’s like saying, while I am free to be soft, I want my partner to be hard – in fact, the harder the better!

This reveals a quiet contradiction in the fem ideal of queer authenticity.

It’s a valid paradox. While the fem gay man rejects the pressure to be masculine in his own presentation, through his preference for “macho” or “hard” partners, he unwittingly validates the same performed masculinity that often fuels their marginalisation.

3 Ways to Resist Masc4Masc Pressure

- Affirm Your Authentic Expression: Celebrate your authentic self. Masculinity can come with softness, and in the flamboyance of femininity lies some quiet strength. Attraction rooted in authenticity is more sustainable than performance.

- Curate Safer Dating Spaces: Challenge exclusionary language. Build micro-communities where fluidity is celebrated.

- Reframe Masculinity Narratives: Embrace range and spectrum. Share stories that expand what masculinity can look like.

🧠 Mantra:

“My worth isn’t defined by how rugged my masculinity appears — it radiates through the authenticity of who I am.”

Conclusion

Femophobia—disdain for femininity in men—isn’t just a dating preference. It’s a symptom of internalised homophobia, shaped by a world that equates queerness with weakness. In response, many gay men adopt hyper-masculine personas to feel safer, more desirable, or more “manly.”

But this performance comes at a cost. Research shows that suppressing authentic self-expression leads to fractured identity, strained relationships, and long-term mental health struggles. To build truly liberating queer spaces, we must dismantle rigid gender norms and embrace the full spectrum of masculinity and femininity—without shame, without apology.

Daniel Nkado is a Nigerian writer, editor, and author best known as the founder of DNB Stories Africa, a digital platform covering Black stories, lifestyle, and queer culture.

📚 References

- Fischgrund, B. N., Halkitis, P. N., & Carroll, R. A. (2012). Conceptions of hypermasculinity and mental health states in gay and bisexual men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 13(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024836

- Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2009). Internalised homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 56(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012844

- Gerrard, B., Morandini, J., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2022). Gay and Straight Men Prefer Masculine-Presenting Gay Men for a High-Status Role: Evidence from an Ecologically Valid Experiment. Sex Roles, 88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01332-y

- Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalised stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 56(1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014672

- Sánchez, F. J., & Vilain, E. (2012). “Straight-Acting Gays”: The Relationship Between Masculine Consciousness, Anti-Effeminacy, and Negative Gay Identity. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 41(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9912-z