By Daniel Nkado.

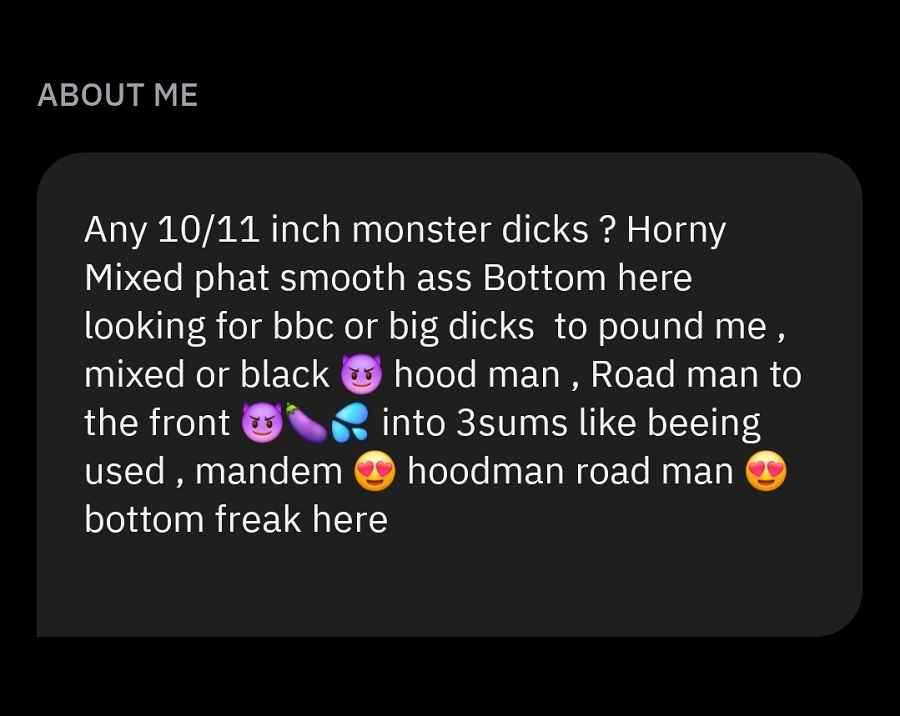

On apps like Grindr, Scruff, or Jack’d, many Black gay and bisexual men notice a distinct pattern: their inboxes fill up faster than those of their peers, but the quality of connection is often vastly different.

Messages range from a generic “Hey” to immediate, explicit propositions. At first glance, this might look like a win in a world that often treats Black queer men as invisible.

However, for far too many, this flood of attention quickly reveals itself as some form of fetish, most notably the BBC or Big Black Cock fetish—a racialised script that reduces a complex human being to a stereotype born in pornography and rooted in centuries of anti-Black racism (Goss, 2021)5.

The “BBC” fetish isn’t praise — it’s a racialised script that turns Black gay men into a box of consumable traits (big size, aggression, street thug).

This article traces the origins of this fetish, reveals how it harms Black gay men and fractures Black queer spaces, and offers actionable steps to reclaim dignity and rebuild collective power.

What the ‘BBC’ Fetish Really Means

The acronym “BBC” is rarely just about size. It acts as a shorthand for three intertwined myths that dominate gay hookup culture (Collins, 20053):

- Hypersexuality: The portrayal of Black men as primal, aggressive, and sexually insatiable.

- Genital Essentialism: The false belief that every Black man is exceptionally endowed, turning natural human variation into a racial mandate.

- Top-Only Dominance: The expectation that Black men exist solely to aggressively “top” or “breed” non-Black partners, often with degrading or violent undertones.

These concepts are not new. They are direct descendants of the “Black brute” caricature used historically to justify the policing of Black men (Alexander, 2012)1. Today, however, they are repackaged as a sexual “preference.”

As one Black gay man shared in an online forum:

“One guy literally said, ‘Then what’s the point of you being Black, if you don’t top?’ when I told him I’m a verse bottom who prefers affection over aggression.” (r/BlackLGBT, 2023)

To understand how widespread this dynamic is, we can look at both platform data and academic research.

The Numbers: A Story of Widespread Objectification

Statistics from academic research and platform data paint a stark picture of how racialised fetishisation operates in the digital space.

- The “Desirability” Gap: In a comprehensive analysis of dating data from 2009–2014, OkCupid found that Black men were, on average, rated as the least desirable racial group overall by non-Black users. Yet, paradoxically, racialised sexual search terms remained extremely popular (Rudder, 2014)10.

- The Impact of Labels: A 2016 study of Australian gay and bisexual men revealed that profiles explicitly mentioning “BBC,” “thug,” or “big Black dick” received dramatically more messages than profiles of Black men who did not reference race or genitals (Callander et al., 2016)2.

- Mental Health Toll: A 2021 study exposed how algorithmic systems of dating apps and porn platforms fuel the hypersexualisation of Black men by rewarding fetish-coded language and search patterns. This dynamic, the authors note, severely impacts Black men’s mental health, self-esteem, and ability to form authentic relationships (Wade et al., 2021)11.

- Market Forces: Pornhub’s 2023 Year in Review confirmed that categories like “Ebony” and search terms such as “BBC” rank highly in global and U.S. searches, evidencing the massive commercial market driving these stereotypes (Pornhub Insights, 2023)7.

While the “BBC” fetish is pervasive on dating apps like Grindr and Jack’d, not every expression of desire from non-Black men fits this category. Some act on genuine attraction, while others unknowingly mimic pornographic tropes without understanding their weight. Naming this harm doesn’t require assuming malice in all cases; it simply requires distinguishing between person-centred desire and dehumanising objectification. ❤️

Preference vs. Fetish: Knowing the Difference

A common defence in dating apps is, “It’s just a preference.” However, a genuine preference is flexible and individual (unique to a person), whereas fetishisation is rigid and reductive.

| Question | ✅ Genuine Preference | 🚩 Racial Fetishisation |

|---|---|---|

| Flexibility (How rigid is the desire?) | Flexible & Open. You might have a “type,” but you are open to surprises. “I usually like tall guys, but I really like your vibe.” | Rigid & Mandatory. The attraction relies 100% on race. If the race factor is removed, the interest is gone. “I only like Black guys who are hung and dominant.” |

| Reaction to Variance (What if he breaks the script?) | Curiosity. If he wants to cuddle or bottom, you adapt because you like him. “Totally cool, I’m down for whatever feels good.” | Disappointment/Anger. If he doesn’t fit the stereotype (e.g., he is soft or bottoms), the attraction collapses immediately. “What’s the point of you being Black if you don’t top?” |

| Scope of Interest (What are you looking at?) | The Whole Person. You see his job, his humour, his flaws, and his humanity. “I’d love to hear more about your photography.” | The Body Parts. You see a walking porn category or a prop for your own pleasure. “Send a dick pic. Is it big?” |

| Emotional Aftermath (How does he feel after?) | Connection. He feels seen, validated, and respected as an equal. | Empty & Used. He feels dehumanised, like an object used to scratch an itch. |

💡 Quick Guidance for Better Connections on Grindr, Hinge, Jack’d

- If you’re messaging: Ask about his interests or day before commenting on his race or anatomy.

- If you’re writing a bio: Lead with a human detail (job, hobby) and a short boundary line (e.g., “Not a category. No fetish talk.”).

- If you’re being fetishised: Remember that “No” is a complete sentence. You have the right to block, report, or ignore anyone who makes you feel like a product.

The “In-House” Problem: Black men fetishising other Black men

Fetishisation doesn’t only come from outside the community. Many Black gay men also internalise and reproduce these same stereotypes.

Intraracial objectification occurs when Black men desire other Black men not for shared culture or genuine connection, but for the same racialised stereotypes seen in porn (Ferber, 2007)4.

Why It Happens: Cultural forces like pornography, racial tropes, and internalised models of masculinity shape erotic attraction. These forces influence how Black men assess and are assessed by partners, even within their own racial group.

Healthy Attraction Intraracial Fetish

| Healthy Attraction | Intraracial Fetish |

|---|---|

| “I love our shared culture, our skin, and I feel safest with other Black men.” (Rooted in connection). | “I only date Black guys who look like thugs/hood dudes.” (Rooted in a caricature). |

Consequences: While intersectional differences (class, social status, body type, age, and immigration situation) shape how Black gay men experience desire and harm, they never justify objectifying one another.

Fetishisation—whether internal or external—reduces people to commodities and reinforces harmful hierarchies. Naming this clearly protects vulnerable members and strengthens collective accountability.

Harmful Consequences of Racialised Fetishisation

Fetishisation isn’t a “personal preference.” It is a mechanism that sustains many racialised harms that extend from private spaces into community and public life.

a. Reinforces the “Dangerous Black Man” narrative (e.g., thug, Mandingo). This script sponsors one of the most harmful biases against Black men, which makes extra suspicion and harder policing feel justified. Sexual stereotypes spill into workplaces, courts, and public spaces, intensifying surveillance and harsher judgment. The BBC fantasiser at night might be acting hypervigilant when he sees a Black man in the morning (Robinson, 2015)8.

b. Fetishisation reduces people to roles, where their vulnerability, emotional needs, and mental health struggles do not matter. Intimate encounters become one-sided, centring the fetishiser’s fantasy and leaving the other partner emotionally drained (Husbands et al., 2013)6.

c. Loss of individuality and a fragile self-worth. Over time, Black gay men internalise these expectations, thinking it is the only thing that makes them valuable. As a result, many respond by always wanting to top or feeling the need to constantly defend their “top” status—acting dominant, performing hypermasculinity, or projecting a macho persona to secure attention. Soon, the community itself learns to treat anyone who deviates as a sellout, because why wouldn’t anyone want to be valued?

d. Mental health issues. Constant objectification produces shame, isolation, anxiety, and depression, while discouraging openness.

e. Monetises Black bodies: Media, porn, and dating‑app cultures monetise racialised fantasies, turning Black bodies into profitable stereotypes. Repeated exposure teaches some Black people to equate their worth with these narrow portrayals (Stacey & Forbes, 2021)9.

How to Move Toward Real Connection

a. For Non-Black Gay/Bi Men

Pause and reflect before sending that message.

- Check your language: Are you leading with race or anatomy?

- Check your expectations: Would you still be excited if he wanted to go on a date, cuddle, or be the receptive partner?

- Check your source: Are you consuming Black bodies the way mainstream porn taught you, or are you seeing a full human being?

For Black Gay/Bi Men

Your worth is not tied to a stereotype.

- Block freely: It is okay to block anyone who opens with “BBC,” “mandingo,” or objectifying language.

- Seek reciprocity: You deserve partners who ask about your day before asking for explicit photos.

- Define your pleasure: It is okay to want romance, gentleness, and equality.

Bio Templates for Filtering Fetishisation On Apps

You can copy and paste these profile protection scripts into your apps. Edit accordingly if needed.

| Platform | Option 1: Direct & Firm | Option 2: Casual & Conversational |

|---|---|---|

| Grindr | “Not a category. Here for connection, not porn.” ❌ If your opener says “BBC,” “thug,” or “breeding” you will be blocked. ✅ Into [Hobby] — ask me about it. | “Not a kink. Here for real vibes.” No racial/fetish talk. ✅ Pizza, movies, and actual conversation. |

| Jack’d | “I’m a [Job] who happens to be Black—not a stereotype.” I don’t respond to racialised comments. Ask me about [Interest] instead. | “More than a type.” Swipe left if you’re looking for a ‘BBC’ fantasy. Swipe right if you like [Interest 1] and [Interest 2]. |

| Hinge | “I’m a [Job] who happens to be Black—not a stereotype.” I don’t respond to racialised comments. Ask me about [Interest] instead. | “Looking for the real thing.” Hoping to meet someone who wants to know me, not a fantasy. I love [Interest] and good food. |

Platform Specificity:

- Grindr scripts are short because attention spans are short there.

- Hinge scripts are softer because the app is designed for dating.

- Jack’d sits in the middle, allowing for a mix of directness and personality.

3 “Green Flags” to Look for in Messages

Once you set your bio, look for these signs that a guy actually reads it and respects you:

- He references your interests: He asks about the hobby or job you listed, not just your body parts.

- He talks about himself: Fetishists often hide; genuine guys share who they are because they want a two-way connection.

- The pace is respectful: He doesn’t demand “BBC” photos immediately but is willing to chat for a bit to establish a vibe.

Conclusion

Being desired should not feel like a reduction. The “BBC” fetish is not a compliment; it is a monetised stereotype that harms individuals and divides communities.

True dignity requires identifying and resisting the system profiting from racialised desire, setting clear boundaries, and creating spaces where Black gay men are valued as whole people rather than narrow fantasies.

Daniel Nkado is a Nigerian writer, editor, and author, best known as the founder of DNB Stories Africa, a digital platform covering Black stories, lifestyle, and queer culture.

References

- Alexander, M. (2012). The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colourblindness. The New Press. https://thenewpress.com/books/new-jim-crow

- Callander, D., Holt, M., & Newman, C. E. (2016). ‘Not everyone’s gonna like me’: Accounting for race and racism in sex and dating web services for gay and bisexual men. Ethnicities, 16(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796815581428

- Collins, P. H. (2005). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203309506

- Ferber, A. L. (2007). The Construction of Black Masculinity. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 31(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723506296829

- Goss, D. F. (2021). Race and masculinity in gay men’s pornography: Deconstructing the big black beast. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Race-and-Masculinity-in-Gay-Mens-Pornography-Deconstructing-the-Big-Black-Beast/Goss/p/book/9781032138572

- Husbands, W., Makoroka, L., Walcott, R., Adam, B. D., George, C., Remis, R. S., & Rourke, S. B. (2013). Black gay men as sexual subjects: race, racialisation and the social relations of sex among Black gay men in Toronto. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(3/4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2012.763186

- Pornhub Insights. (2023). 2023 Year in Review. Pornhub. [Link Removed For Niche Safety]

- Robinson, B. A. (2015). “Personal Preference” as the New Racism. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(2), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649214546870

- Stacey, L., & Forbes, T. D. (2021). Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialised Feelings, Fetishisation, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Gay Dating Apps. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1979455

- Rudder, C. (2014). Dataclysm: Who We Are (When We Think No One’s Looking). Crown. https://harpercollins.co.uk/products/dataclysm-who-we-are-when-we-think-no-ones-looking-christian-rudder

- Wade, R. M., Bouris, A. M., Neilands, T. B., & Harper, G. W. (2021). Racialised Sexual Discrimination (RSD) and Psychological Wellbeing among Young Sexual Minority Black Men (YSMBM) Who Seek Intimate Partners Online. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00676-6