by DNB editorial team.

As Griff croons in her haunting track Earl Grey Tea:

“You’re so scared you’re aging faster / So you drink Earl Grey tea ’cause you heard that’s the answer.”

It hits like a soft confession — one many gay men understand too well.

That quiet panic.

That instinct to tug at your cheeks in the bathroom mirror.

That urge to shave five years off your dating bio.

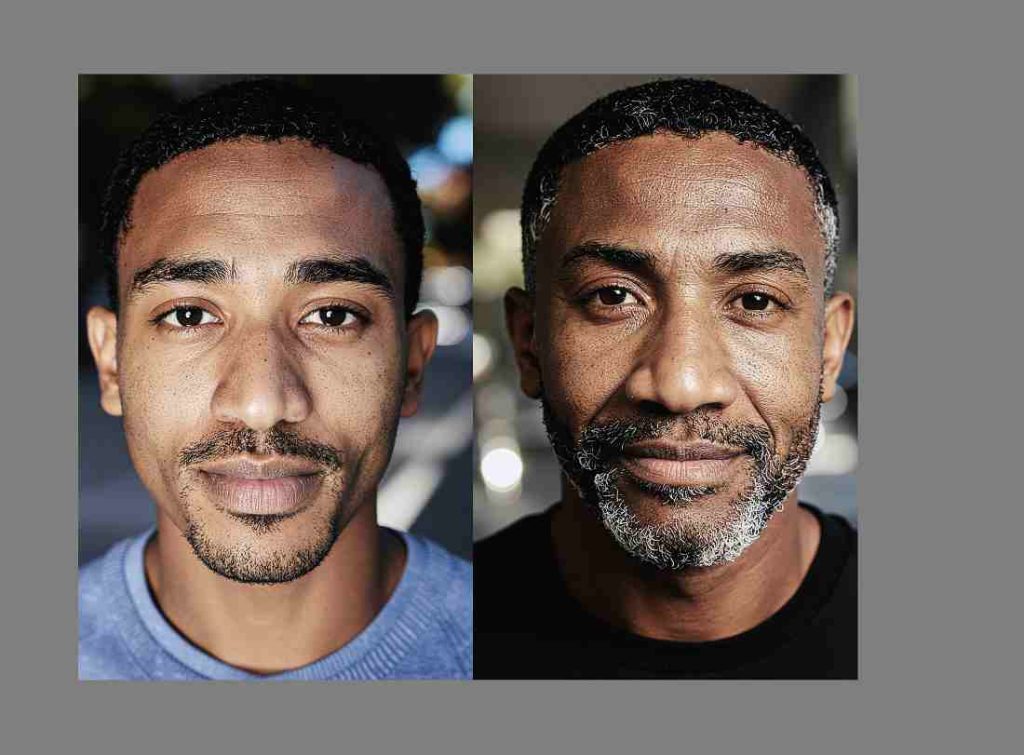

In a community where ages are whispered, edited, or omitted entirely — where youth is an unspoken currency — ageing can feel like slipping out of the frame. For a 44-year-old gay man, this is not theory; it is felt in the body, the gradual tiredness and helplessness you feel about things that once sparked real excitement, the way strangers tilt their heads and read you as “old, wise, mysterious.” The pang you felt the first time you read “no one over 30” in the beautiful Grindr profile you were just about to message.

But why does ageing strike such a deep chord in gay men? Why does it stir fear, dread, or quiet shame in a community that fought so hard to love itself?

The answers to this fear lie in our history, our culture, our psychology, and in the world we grew up resisting in one way or another. Understanding how these forces overlap — and how deeply they shape our sense of worth and belonging — may be the first step toward reclaiming what ageing should look like for us: a process rooted in dignity, pride, and community rather than disappearance and fear.

1. Youth as social currency in gay culture

Gay male culture often treats youth like social currency. From the shirtless bodies on Instagram to emotionless dating app bios that read “my age or younger only”, the message is simple: younger = hotter = more valuable.

Straight men, culturally, have alternative status markers — fatherhood, marriage, career expectations — that cushion the loss of youth’s glow. But gay men, excluded from these traditional paths for generations, often learn to anchor self-worth to the body and its perceived desirability (Hudson, 2018)4.

Historically, many gay spaces focused on nightlife, physical freedom, and sexual expression — places where youthfulness signalled value and desirability (Hajek, 2018)3.

And today, this plays out on almost every aspect of gay social life, loudest even on dating apps and social media:

- “25 is old in gay years.”

- “If you’re over 35, don’t message me.”

- “You look great for your age”, — said as though it’s extraordinary to age at all.

In these environments, ageing can feel like a slow fade into invisibility — not due to fading beauty as maturity does carry its own quiet allure —but because this stage often signals a descent into the community’s shrinking mirror of desirability.

2. Impact of AIDS – A loss that lingers

Ageing in gay culture is not merely aesthetic — it’s historical. The AIDS generation was nearly erased.

The 1980s and 90s removed an entire cohort of gay elders. Entire lineages of mentorship, humour, sexuality, and support were lost. Those who survived often carry survivor’s guilt and grief — a distorted relationship to time itself (Orel, 2014)7.

For many, growing old feels like something they were never taught how to do. There was no template, no role model, no “this is what 50 looks like for us.”

Structural exclusion caused more issues

Structural exclusion added extra problems. Marriage equality, adoption rights, and societal acceptance came late for queer people. Many older gay men entered midlife without family structures, institutional support, or legally recognised partnerships (Brennan-Ing et al., 2022)1. Ageing, for them, is not simply about wrinkles — it is about the fear of being alone, with no safety net.

How intersectionality compounded invisibility for Black gay men

For Black and African queer men, the fear of ageing is further complicated by intersectionality. The challenge is not just ageism but the compounded burden of racism, homophobia, and ageism—a triple threat to stability and self-worth (Woody, 2017)10.

Stigma, religious pressure, family expectation, and criminalisation (in many countries) deepen the dread of ageing alone or ageing invisibly.

Many queer Africans describe an added fear:

- Who will care for me if my family rejects me?

- Who will see me if my community doesn’t?

These realities complicate the already-fragile terrain of ageing as a gay man, often magnifying the feeling that a safety net doesn’t exist.

3. The psychological toll of gay ageism

Research shows that gay men often internalise community ageism.

This is known as internalised gay ageism — a form of minority stress where self-worth deteriorates under the pressure to remain perpetually youthful (Sharma & Subramanyam, 2024)8.

This internal pressure can lead to:

- Anxiety and depressive symptoms: Studies show older gay men report significantly more negative views of ageing and related mental-health challenges than heterosexual men (Wight et al., 2015)9.

- Social withdrawal: Feeling “past your prime” can lead to isolation — especially for single gay men who fear ageing will block romantic or sexual connection.

- Desperate attempts to “stay young”: From extreme fitness routines to cosmetic interventions to compulsive app use, many gay men chase the illusion of eternal youth to remain visible.

- Relationship strain: Age gaps attract stigma, and men who come out later in life often feel doubly marginalised — both in mainstream society and gay spaces.

All these factors combine to reinforce the same message: Ageing makes you less worthy. A lie that harms more than just individuals, but weakens the broader gay community.

4. Rewriting the script of queer ageing — 4 practical steps

Ageing does not have to be a descent into invisibility. Gay men across the world — especially those who have already carved space through trauma — are building new templates for what queer ageing can look like.

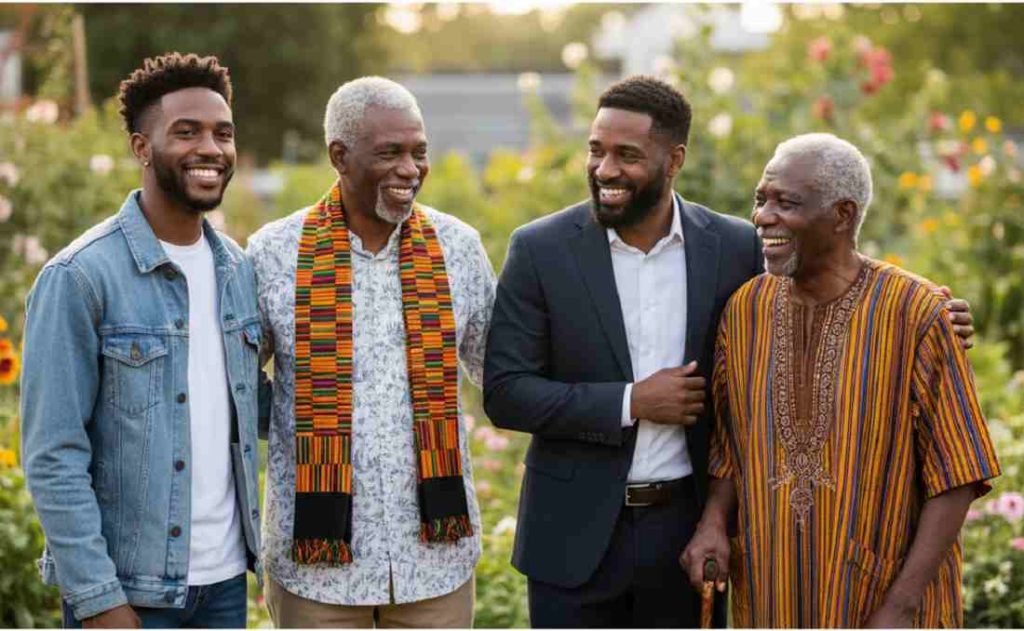

a. Establish mentorship and skill-sharing programs 🧑🤝🧑

Mentorship and community care significantly improve well-being among older LGBTQ+ adults (Meri-Esh and Doron, 2009)6. Creating structured and mutually beneficial relationships between generations of older and younger queer persons is a good way to change the story of queer ageing from that of anxiety to purpose and shared connection.

- Host a “Queer History Hour”: Younger gay men can invite older community members to share personal stories, experiences, and lessons learned about survival and activism. This provides visibility to elders and historical context to the youth.

- Launch a “Digital Buddy” Program: Organise younger, tech-savvy men to offer one-on-one help to elders with smartphones, dating apps, or navigating online healthcare.

- Form a Community Skill-Share: Older men can mentor on life skills (e.g., financial planning, cooking, home repair, career navigation) that are often missed without traditional family structures.

b. End segregation in community spaces ☕

Social isolation and negative views of ageing are linked to mental health challenges. Visibility and inclusion are essential steps for healing (Lyons et al., 20215; Wight et al., 2015)9. Don’t wait for organisations to create new spaces; change the culture of existing ones through personal initiative.

- Mandate “Intergenerational Mingling” at Queer Events: If you are a host or attendee, proactively introduce yourself to someone at least 15 years older or younger than you. Make it a personal goal to break up age-segregated groups.

- Diversify Your Digital Feed: Younger men should deliberately follow and engage with older queer creators, thinkers, and artists on social media.

- Champion Age-Positive Language: Individuals should speak up—politely but firmly—when they hear ageist comments or see exclusionary bios on dating apps, refusing to let them become normalised community currency.

c. Build local “chosen family” structures for older queer men🏡

Strengthening social care networks and social support networks reduces vulnerability, particularly for older LGBTQ+ adults who entered midlife without legally recognised partnerships or traditional family structures (Brennan-Ing et al., 2022)1.

Focus on creating small, committed support structures that mitigate the greatest fear: ageing alone.

- Start a Weekly Check-In Pod: Form a small, mixed-age group of 4-6 queer friends who commit to a quick, reliable weekly check-in (text, call, or coffee) to ensure no one becomes isolated or falls through the cracks.

- Organise Care Teams: For elders who may lack immediate family, local peers can volunteer to rotate tasks such as grocery runs, transportation to appointments, or help with small home maintenance tasks.

- Practice Radical Presence: If you notice an older gay man attending community events alone, make a point of sitting with him or ensuring he is introduced to others.

d. Redefine personal value beyond youth 💎

This means rethinking what we value—moving our focus from things like looks and appearance and instead celebrating the lasting qualities and contributions that bring fulfilment, meaning, and a sense of purpose throughout life (Sharma and Subramanyam, 2024)8. This is the internal shift that makes the outward actions possible.

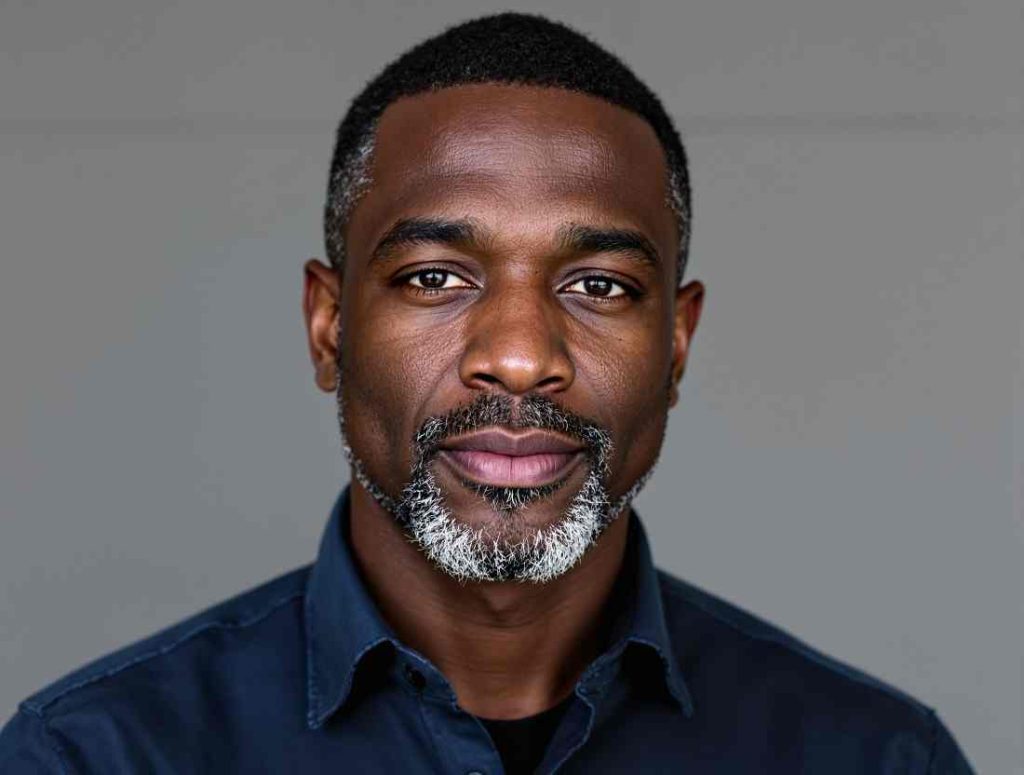

- Celebrate Resilience and Wisdom: For older men, shift self-worth from desirability to dignity. View wrinkles and grey hair not as signs of decline, but as evidence of having survived and thrived in a hostile world.

- Value Emotional Maturity: For all ages, consciously prioritise qualities that grow with age—emotional intelligence, stability, humour, and depth of character—over fleeting physical youth when choosing partners and friends.

e. For every gay individual: Own Your Age

Oya! Own your age— not with shame or apology. But with the quiet knowing that surviving, loving, and becoming are both beautiful and priceless.

"Oya" is a Nigerian pidgin slang term that means "let's go" or "let's get to work".5. A Call for a More Courageous, Connected Community

As gay men, we’ve fought battles for visibility, equality, and self-acceptance. Tackling ageism should be no different.

It starts in small ways:

- sharing stories that help others navigate their own challenges and make informed decisions.

- mentoring across generations.

- refusing to disappear— proving life stays full and meaningful as we age.

- celebrating the men who aged so we could have tomorrow.

Because every wrinkle is not a mark of decline — it is evidence of survival. So maybe it’s time we sip our Earl Grey, not to slow the clock, but to savour the years we earned. Gay or straight, young or old, the most timeless thing about any of us is the courage to keep showing up.

And that courage? It only grows with age!

Resources for Ageing Queer Persons

Ageing queer individuals navigate a unique set of challenges related to identity, health disparities, and societal structures. A curated list of personal resources, designed to support emotional well-being and practical needs, includes:

- Global organisations like SAGE (Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders) and The Trevor Project’s TrevorSpace for community support, which offer both physical and anonymous virtual connection points.

- Health and mental health resources, such as the directories provided by OutCare Health and GLMA, help locate affirming healthcare providers, while apps like Headspace or Q Chat Space offer accessible mental wellness support.

- For financial and legal matters, SAGE’s “Out & Visible” guide and resources from Lambda Legal assist with retirement planning and securing end-of-life decisions.

- Locally in Nigeria, The Initiative for Equal Rights (TIERs) provides vital, confidential legal aid and safety support to navigate the country’s restrictive legal landscape.

Stay Informed: Follow DNB Stories Africa or other global queer platforms (e.g., PinkNews) privately for updates on rights and resources.

References

- Brennan-Ing, M., Seidel, L., Larson, B., & Karpiak, S. E. (2022). Social care networks and older LGBT adults: Challenges for the future. Journal of Ageing & Social Policy, 34(3), 412–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2022.2044243

- Griff. (2021). Earl Grey Tea [Song]. On One Foot in Front of the Other. Warner Records. https://genius.com/Griff-earl-grey-tea-lyrics

- Hajek, C. (2018, May 28). The queer fear of ageing. INTO. https://www.intomore.com/culture/the-queer-fear-of-aging/

- Hudson, D. (2018, August 7). Do gay men have a particular problem with getting older? Medium. https://medium.com/@davidhudson_65500/do-gay-men-have-a-particular-problem-with-getting-older-85a6d4314b3b

- Lyons, A., Alba, B., Waling, A., Minichiello, V., Hughes, M., Barrett, C., Fredriksen-Goldsen, K., Savage, T., & Edmonds, S. (2021). Assessing the combined effect of ageism and sexuality-related stigma on the mental health and well-being of older lesbian and gay adults. Ageing & Mental Health, 26(7), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1978927

- Meri-Esh, O., & Doron, I. (2009). Ageing with pride: A community-based program for older LGBT people. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(4), 303–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720903335353

- Orel, N. A. (2014). Investigating the needs and concerns of LGBT older adults. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.835236

- Sharma, A. J., & Subramanyam, M. A. (2024). Internalised gay ageism: An exploratory study. Society, 61(2), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-023-00946-6

- Wight, R. G., LeBlanc, A. J., Meyer, I. H., & Harig, F. A. (2015). Internalised gay ageism, mattering, and depressive symptoms among midlife and older gay men. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.066

- Woody, I. (2017). Aging out: A qualitative exploration of ageism and heterosexism among ageing African American lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1158173