By Daniel Nkado.

For many gay and bisexual men, the desire for receptive anal sex (bottoming) is thwarted by physical pain, panic, tightening or an inability to “relax.”

Pelvic pain and tightness during receptive anal sex usually come from a mix of physical and psychological factors.

- Physical factors include pelvic-floor hypertonicity/armouring, injury, irritation, low lubrication, medical conditions, etc.

- Psychological factors include anxiety, past trauma, and internalised shame.

These factors often reinforce each other—tension causes pain, and pain triggers even more tightening. The good news is that this cycle can be broken with a supportive mindset and the right techniques.

Helpful, trauma-informed options include:

- Pelvic-floor therapy

- Gentle self-exploration or dildo training

- Toy warm-up before bottoming, and

- Making sure to always use plenty of lubrication

- Mindfulness and nervous-system regulation can also be employed to reduce the anxiety and other negative feelings that create tension (NHS, 2022)9.

These approaches are highly effective, and most people can retrain their bodies to relax, making receptive sex more comfortable, pleasurable, and confident.

Using concrete evidence from trauma neurobiology and pelvic health studies, this article outlines the causes of tension (armouring), ways to recognise it (signs), as well as actionable, trauma-informed pathways to recovery.

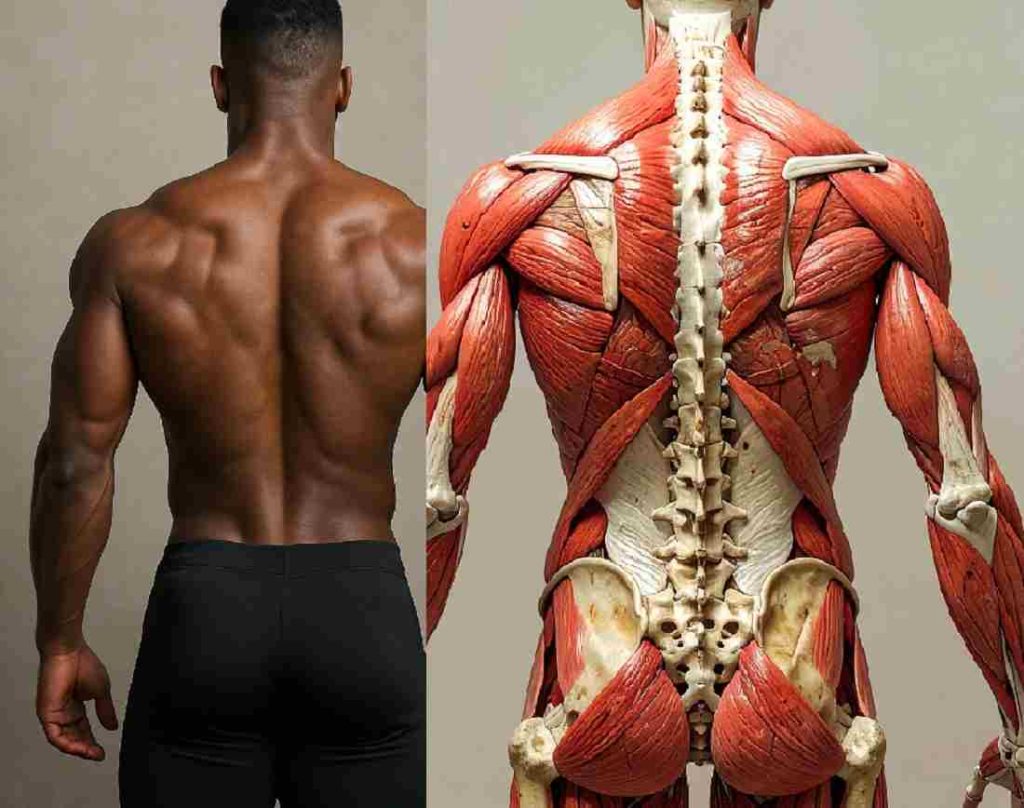

1. What is Pelvic Armouring?

Pelvic armouring is a community term that describes the chronic tightening or guarding of the pelvic floor muscles, often linked to anxiety, past injury, painful experiences, or trauma.

Although pelvic armouring itself isn’t a formal medical diagnosis, the underlying issue is medically recognised as pelvic floor hypertonicity (also called pelvic floor overactivity).

It refers to a form of defence mechanism in which the body mounts and maintains muscle tension to protect against perceived threats, which could be either physical or emotional.

Common symptoms include persistent pelvic tightness, bottoming pain, and involuntary muscle spasms.

The concept of muscular armours was developed by psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, who described how repressed emotions, anxieties, and traumas over time manifest as physical tension and rigidity in specific muscle groups of the body (Gilbert, 1999)6.

2. How it Manifests: Symptoms and Signs

Symptoms vary from person to person but commonly include:

- Chronic pelvic pain, which may radiate to the lower back, hips, groin, or rectum.

- Pain during or after sex (dyspareunia)

- Difficulty with bowel movements, including constipation, straining, or a sense of incomplete emptying.

- Urinary symptoms, such as frequent urination, urgency, hesitancy, or feeling unable to fully empty the bladder.

- Painful urination (dysuria).

- Tailbone pain (coccydynia).

- In men, pelvic hypertonicity can also cause erectile dysfunction, painful ejaculation, or testicular pain (Dorey et al., 2004)2.

While discussed here in the context of gay/bi men, these symptoms (e.g., dyspareunia, urinary urgency) can affect anyone with pelvic hypertonicity, including cis women or trans/non-binary individuals.

3. Causes of Pelvic Armouring/Hypertonicity

There is no single cause of hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction. Instead, it usually develops from a combination of factors such as:

a. Performance Anxiety:

Mainstream pornography sometimes highlights unrealistic depictions of receptive anal sex (bottoming), such as quick, aggressive penetration, which can foster performance pressure. This condition may heighten anxiety during an attempt to bottom, physiologically hindering relaxation (e.g., via elevated cortisol levels).

b. Assimilated Shame and Stigma:

Cultural stigma often codes the anus as “dirty” and bottoming as “unmanly” in many societies. These prejudices, when deeply internalised, can cause tightening and reflexive tension during an attempt to bottom. Internalised stigma has also been linked with higher rates of sexual dysfunction in gay and bi men (Lyons and Pepping, 2017)7.

c. Trauma:

- Sexual Trauma: Past painful sexual experiences can condition the nervous system to interpret penetration as a violation, triggering a reflex contraction.

- Childhood Trauma: High “ACE” (Adverse Childhood Experience) scores are strongly linked to chronic pelvic pain and somatisation in adulthood (Eilers et al., 2023)4.

How Internalised Stigma Causes Physical Tension and Pain

Somatisation occurs when continued emotional stress manifests as real physical symptoms in the body, such as pain, fatigue, or muscle tension.

When symptoms of pelvic armouring are driven by emotional factors like internalised shame/stigma, performance anxiety, or a lack of trust in a partner, it could be described as a form of somatisation Ehlert et al., 1999)3.

Example Scenario:

Okolo identifies as an “Alpha Dom Top” on Grindr and frequently voices the belief that “real men only top.” However, he meets a partner, Lawal, whom he is strongly attracted to and decides to try bottoming. Despite his conscious willingness, he immediately experiences severe pain and tightness. There is no physical injury or inflammation. Instead, Okolo’s nervous system is experiencing a conflict between his desire and his rigid belief.

This is an excellent example of the impact of Role Rigidity and Cognitive Dissonance:

The Conflict: Okolo has a conscious desire (he is attracted to Lawal and wants to try bottoming), but he has a deep-seated subconscious belief (“real men don’t bottom/bottoming is shameful”).

The Result: The brain detects a threat to his identity or likely exposure to shame from the act (per Okolo’s ingrained belief about bottoming) and triggers the sympathetic nervous system, causing the pelvic floor muscles to contract (armour up) to prevent the act. Poor Okolo had no say in this.

By expanding a sexual role to a rigid identity framed by internalised prejudices, Okolo created a psychological conflict called cognitive dissonance —the mental discomfort or uneasiness people feel when their actions do not match their beliefs. This highlights how fluidity in roles can reduce dissonance, benefiting versatility or more open-minded (unprejudiced) individuals.

3. When to seek care

If you suspect you have a hypertonic pelvic floor, it’s important to see a healthcare professional or a pelvic floor physical therapist for assessment. These symptoms rarely resolve on their own, and early, targeted treatment leads to the best outcome.

Evidence-Based Treatments for Hypertonic Pelvic Floor:

A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for treatment and recovery from pelvic armouring. It requires addressing both the tissue (muscles/nerves) and the issue (trauma/safety/injury).

The primary treatment for hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction is pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT), carried out by a specialised pelvic health physiotherapist (Wallace et al., 2019)10.

Other alleviative options include:

- Relaxation and breathing techniques (especially diaphragmatic breathing) to teach conscious release of tense muscles.

- Stretching exercises targeting the pelvis, hip, and surrounding muscles.

- Lifestyle and behavioural modifications, such as better bladder and bowel habits, improved posture, reduced stress, and adapted exercise routines (Cho and Kim, 2021)1.

Practical Steps You Can Easily Try On Your Own

If you are experiencing pain during an attempt to bottom, stop at once. Don’t try to push through. Pain reinforces the danger signal to your brain, making the armouring worse.

i. Immediate Self-Care (During intimacy)

- Pause and Pivot: If sex hurts, stop. Switch to non-penetrative intimacy, at least for that moment.

- Check Your Jaw: If you feel tightness, check if your teeth are clenched. Wiggle your jaw or blow raspberries with your lips to relax the facial muscles.

ii. Mindful reframing (Before intimacy)

Mindful reframing is the conscious act of catching anxious and negative thoughts (e.g., “this might get messy” or “I will lose my top status”) and then actively changing them into balanced, realistic viewpoints:

—”I can use a dildo to check that I am clean before beginning.”

—”I will take my time, and even if it gets messy, it’s not the end of the world.”

—”I’m doing this for myself; my worth is not tied to a sex act.”

By consistently practising mindful reframing, individuals can gradually alter their habitual thinking patterns, reducing overall anxiety and fostering a more positive and resilient mindset (Farb et al., 2012)5.

iii. Self-Exploration (Hole Training):

Experimenting on your own with a lubricated finger or a small toy (like an anal dilator or butt plug with a flared base) can help build confidence and teach you how to control your sphincter muscles.

iv. The Pelvic Drop:

This technique involves relaxing and releasing your pelvic floor muscles after you have contracted them. To begin, inhale deeply into your belly and visualise your pelvic floor dropping/bulging outward (like you are gently pushing out gas).

v. Medication:

In some cases, particularly when pain is severe and not improving with other treatments, muscle relaxants or other medications might be prescribed. You should always consult a doctor for a proper diagnosis before taking any medication.

Daniel Nkado is a Nigerian writer, editor, and author, best known as the founder of DNB Stories Africa, a digital platform covering Black stories, lifestyle, and queer culture.

References

- Cho, S. T., and Kim, K. H. (2021). Pelvic floor muscle exercise and training for coping with urinary incontinence. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 17(6), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.2142666.333

- Dorey, G., Speakman, M., Feneley, R., Swinkels, A., Dunn, C., and Ewings, P. (2004). Randomised controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises and manometric biofeedback for erectile dysfunction. The British Journal of General Practice, 54(508), 819. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1324914/

- Ehlert, U., Heim, C., and Hellhammer, D. H. (1999). Chronic Pelvic Pain as a Somatoform Disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012318

- Eilers, H., Rot, and Jeronimus, B. F. (2023). Childhood Trauma and Adult Somatic Symptoms. Psychosomatic Medicine, 85(5), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000001208

- Farb, N. A. S., Anderson, A. K., and Segal, Z. V. (2012). The Mindful Brain and Emotion Regulation in Mood Disorders. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700203

- Gilbert, C. (1999). Breathing: the legacy of Wilhelm Reich. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 3(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1360-8592(99)80029-1

- Lyons, A., and Pepping, C. A. (2017). Prospective effects of social support on internalized homonegativity and sexual identity concealment among middle-aged and older gay men: a longitudinal cohort study. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(5), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1330465

- Masterson, T. A., Masterson, J. M., Azzinaro, J., Manderson, L., Swain, S., & Ramasamy, R. (2017). Comprehensive pelvic floor physical therapy program for men with idiopathic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(5), 910–915. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2017.08.17

- NHS. (2022, September 14). Mindfulness. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/self-help/tips-and-support/mindfulness/

- Wallace, S. L., Miller, L. D., & Mishra, K. (2019). Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 31(6), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1097/gco.0000000000000584

patronise a fellow gay