In gay culture, “top,” “bottom,” and “vers” were never meant to be social identities or personality types. They were supposed to be simple communication tools — a quick way to say what you enjoy sexually.

But somewhere along the way, these labels hardened into a hierarchy and became status symbols, markers of masculinity, and social currency.

This article examines how gay men—especially within Black gay communities—navigate the “social currency” of sex roles, the psychological impact of role pressures, and how a bold, absurdist reframing declaration can open the door to personal healing and liberation.

- 'Masc4Masc' economy and the gendering of sex roles

- How Role Hierarchies Form — Top vs Bottom Dynamics

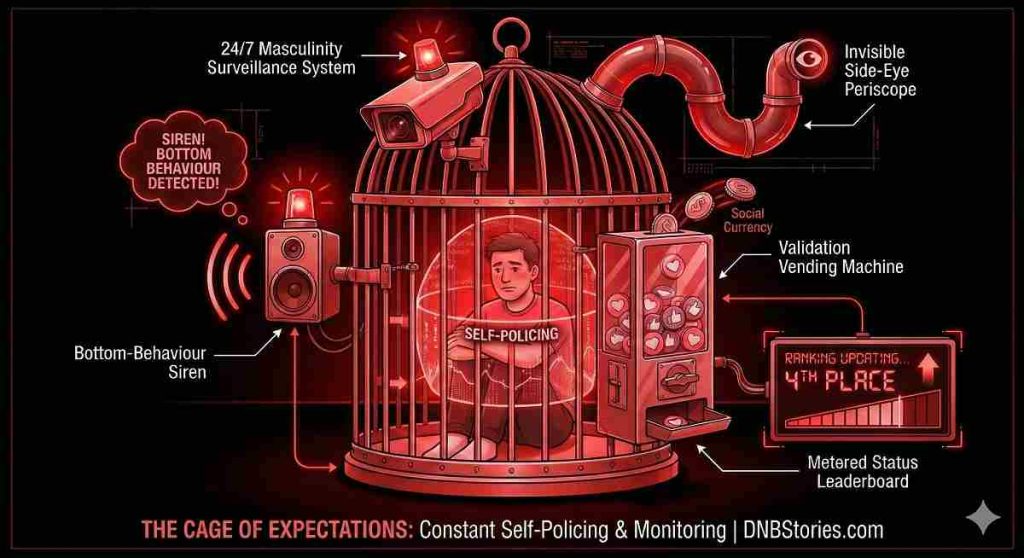

- Role-Based Anxiety: The Cage of Expectations

- Masculinity Policing: The Unique Case of Black Gay Men

- Red Flags: How To Know Your Role Has Caged You

- Breaking Out: The Psychology of the Scream

- The Absurdity Reps Method (ARM)

- Why This Matters for Black Queer Men

- References

‘Masc4Masc’ economy and the gendering of sex roles

Multiple studies have shown how sexual roles often get gendered:

- “Tops” are coded as masculine, dominant, and high‑status.

- “Bottoms” get coded as feminine, submissive, and lower‑status (Dangerfield et al., 2017[2]; Johns et al., 2012)[7].

These meanings don’t come from our bodies (no body part tells you you’re a top or a bottom) or our honest desires. They come from patriarchy, racism, homophobia, and the pressure to perform masculinity in a world that already questions it for queer people.

But when roles become status symbols, men stop seeking pleasure and start defending their reputation. And this is how ordinary sexual terminology starts shaping how men judge themselves and each other. In social spaces and dating apps like Grindr, Jack’d, or Scruff, this shows up through codes like “straight-acting,” “masc4masc,” and “total top-no fems” —language that reward performative masculinity while punishing softness (English et al., 2024)[3].

This situation could also explain why many gay men worship macho behaviour performance.

How Role Hierarchies Form — Top vs Bottom Dynamics

When sexual roles become mixed with cultural scripts about masculinity and dominance—mostly inherited from heterosexual norms—they stop functioning as neutral bedroom preferences and turn into a ranking system that judges performance rather than the person.

Studies show that many gay and bisexual men internalise heterosexual norms of masculinity and impose them onto gay culture, using them to mark hierarchies and police desirability (Moskowitz & Hart, 2011)[8]. A study published in the Archives of Sexual Behaviour found that gay men who prioritise masculine traits often devalue “bottoming” due to internalised femiphobia (fear of femininity).

Other related studies link the shame associated with bottoming — often called “bottom shaming” — to anxiety, reduced sexual wellbeing, and internalised stigma (Vytniorgu & García‑Iglesias, 2025)[12].

Today, when someone says “I’m not a bottom,” they usually don’t mean “I don’t enjoy receptive anal sex.” They’re really saying, “I am not a feminine, submissive, or lower‑status gay man.”

Role-Based Anxiety: The Cage of Expectations

When sex roles become standards for judging others, expectations are created — tests that determine if you pass or fail. These expectations (tests) create pressure (through fear of failure). Pressure puts you in a cage, ensuring you don’t make a mistake and fail (constant self-policing).

And that’s how masculinity—or a good performance of it—becomes currency: those who pass the test earn status, and you keep performing to avoid dropping your score (Reigeluth & Addis, 2021)[11].

I call this constant self-policing and monitoring the “Cage of Expectations”, equipped with a 24/7 masculinity surveillance system, an invisible side-eye periscope, a bottom-behaviour siren, a validation vending machine, and a metered status leaderboard that updates your ranking in real time.

Masculinity Policing: The Unique Case of Black Gay Men

These dynamics are significantly amplified in Black gay culture, where the intersection of race and sexuality creates unique pressures.

From slavery-era “Buck” to modern Grindr “Top”

During slavery, physical resilience and rugged masculinity were exploited as economic value — stronger enslaved men were literally more profitable. At the same time, a myth of sexual dominance was projected onto enslaved Black men to confine them to their bodies and suppress any recognition of their intellect — a strategy that worked perfectly, fuelling the narrative of Black men as powerful bodies with diminished minds across many societies.

Scholars argue these tropes persisted and evolved into modern-day objectification and fetishisation of Black bodies we see today — including the “BBC”, “Black Beast” and “Mandingo” tropes in media and pornography (Collins, 2004)[1].

This may help explain the familiar pattern in gay dating where many non‑Black gay men seem to want Black gay men in their beds but not in their lives — almost like a quiet way of saying the body and what it’s imagined to “do” is welcomed, but the actual person is not.

But the deeper harm, I personally think, is what seems like an ongoing erasure of intellect as a legitimate marker of status among Black men. In many Black queer spaces, particularly on apps like Grindr and Jack’d, the body and performance of masculinity are notoriously privileged over the mind, influencing desirability, attention, and the default assumption of ‘fun’ versus ‘serious.’

Conversations often quickly assess physique and masculinity profile instead of valuing curiosity, humour, or critical thinking. Consequently, intellectual depth is undervalued, leaving Black men who lead with their minds feeling invisible unless their bodies meet a narrow ideal.

Red Flags: How To Know Your Role Has Caged You

Look for these signs of role rigidity:

- Aggressive Defence of Status: You feel genuine anger if someone suggests you might be versatile. You use qualifiers like “Total,” “Strictly,” or “Alpha” not to defend your preference, but to defend your worth.

- Role Anxiety: You avoid certain behaviours (e.g., dancing a certain way, showing emotion, crossing your legs) because they are “for bottoms.”

- Policing: You judge these behaviours in others (“How can you be top if you listen to Taylor Swift?”)

- Social Avoidance: You distance yourself from people and activities perceived as “for bottoms” to avoid guilt by association.

- You are chasing phantom exclusives: A gay man only looking to bottom for “straight-passing” dominant DL tops. “My bottom cannot top me” is no longer about sex — it’s gender policing (Ravenhill & de Visser, 2017)[10].

Breaking Out: The Psychology of the Scream

This may sound silly — the underlying principle is actually called Absurd Reframing — but it’s one of the most effective ways to disrupt role‑based anxieties and pressures.

It works by transforming the rigid, fear‑based logic of role hierarchies into something so exaggerated and theatrically absurd that your brain can no longer take it seriously. The brain can’t cling to a hierarchy it can no longer take seriously.

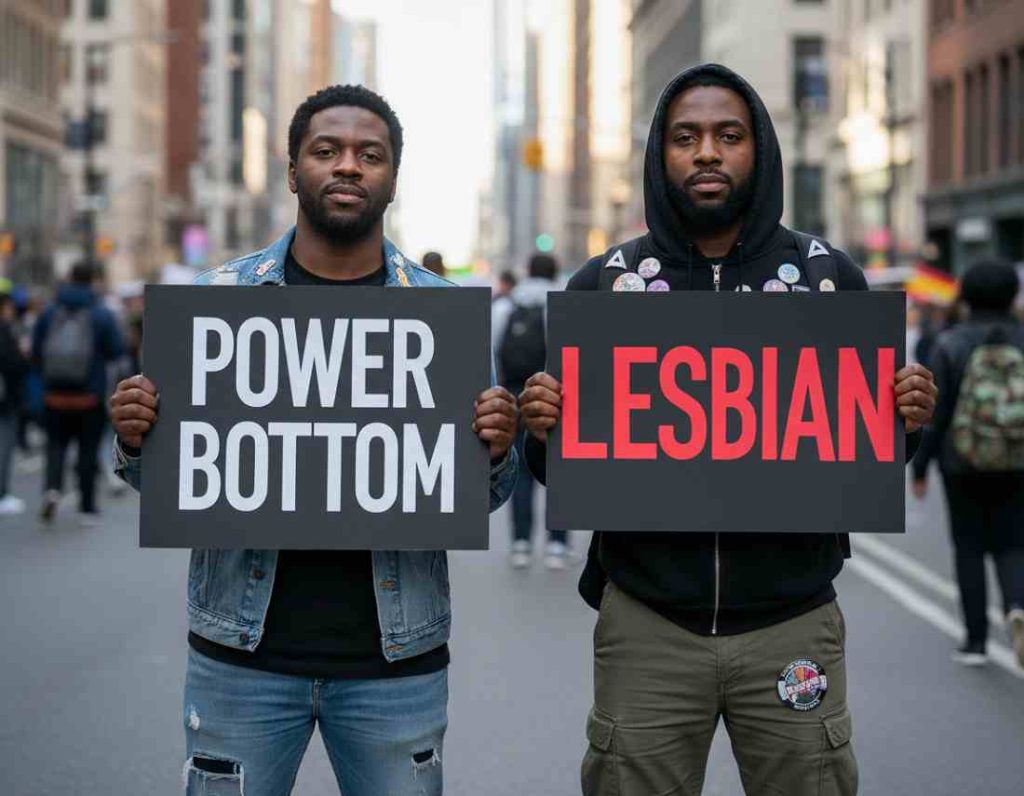

Scream something that contradicts the script so completely that the hierarchy glitches. Having witnesses (such as a group) increases efficiency. Posting on social media also works, but test in a low-risk first, e.g., a Close Friends group on Instagram.

Tops: “I’m a power bottom lesbian!”

Bottoms: “I’m a macho DL top with three girlfriends!”

It may sound ridiculous. But that’s the point. Absurdity is basically humour as healing.

How Absurdity Works

Absurdity is a psychological tool disguised as a joke. It works by breaking the script’s rigidity.

- It creates cognitive dissonance

- Cognitive dissonance is the discomfort we feel when our beliefs and actions don’t match. When you say something intentionally contradictory in public — “I’m a power bottom lesbian” — your brain feels it and begins to loosen its grip on rigid beliefs. At the community level, owning the term neutralises the shame associated with bottoming.

- It reframes identity

- Reframing helps people separate identity from behaviour (Padesky, 1994)[9]. Absurdity creates distance between who you are and what you do. You stop treating sexual roles as destiny.

- It rewrites the story

- Narrative therapy teaches that when you change the story, you change the self (White & Epston, 1990) [13]. Absurdity is a shortcut to rewriting the story of your sexuality — from rigid to fluid, from policed to playful.

The Absurdity Reps Method (ARM)

- Definition:

- A simple, repeatable tool that uses humour and reframing to loosen role‑based shame and anxiety.

- Promise:

- To help queer people — especially Black queer men — break free from the anxiety, shame, and performance pressure tied to sexual roles and masculinity scripts.

- Limitations:

- Absurdity isn’t the whole solution — but it’s a start. A crack in the wall.

- This technique is best suited for mild to moderate role-based anxiety and shame.

- It is not sufficient for addressing acute crisis, depression or deep trauma that require personalised care.

- This technique is practice‑oriented, and, like any emerging method, it will require further testing and empirical validation to assess its effectiveness across different contexts.

- It also requires care when practised in hostile or unsafe environments.

- And, most importantly, this method is not designed to replace the guidance of a trained professional.

Absurdity Reps — A Quick Guide

Absurdity Reps are small, repeatable moments where you say something intentionally ridiculous and contradictory about your sexual role or expression in public. They work like emotional or cognitive “gym reps” — each one loosens the grip of shame, rigidity, and performance.

A Simple Absurdity Rep To Try Today

Something that breaks your usual role script in a group:

Tops say:

- “I’m a power bottom lesbian.”

- “I’m a pillow princess bottom.”

Bottoms say:

- “I’m a power top from Narnia.”

- “I’m a dominant alpha top from Middle‑earth.”

Then notice what shifts — tension, self‑monitoring, the need to perform.

Follow with a truth:

- “I’m tired of roles being a hierarchy.”

- “I’m allowed to be fluid.”

- “My softness is not a liability.”

- “My worth is not tied to a role.”

The truth must be clean, contained, and universal enough to resonate. When you follow Absurd Reframing with a truth, the truth needs to stabilise, not spill. So a life story, trauma disclosure, confession or vulnerability spiral will not work.

⚠️Only use Absurdity Reps in spaces where you feel reasonably safe; in hostile environments, practice privately or with trusted friends.

Why This Matters for Black Queer Men

For Black queer men, role expectations often collide with racialised masculinity scripts. Society already demands that Black men be strong, stoic, dominant, and unbreakable. Add homophobia, and the pressure doubles. Add queer community hierarchies, and it triples (Han, 2008)[6].

Absurdity is a form of resistance. A refusal to be boxed in. You’re not a top or a bottom. You’re a whole person. If a label can’t survive a joke, it shouldn’t run your life.

This is to a future without role hierarchies — a world where a Black queer man can say, “I’m a bottom,” not as an act of resistance, but with the same neutrality as saying, “I like sushi.”

References

- Collins, P. H. (2004). Black Sexual Politics. Routledge. https://we.riseup.net/assets/247932/Black-Sexual-Politics

- Dangerfield, D. T., Smith, L. R., Williams, J., Unger, J., & Bluthenthal, R. (2016). Sexual Positioning Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Narrative Review. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 46(4), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0738-y

- English, D., Carter, J. A., Forbes, N., Aria Tilove, Smith, J. C., Bowleg, L., & H. Jonathon Rendina. (2024). “Straight-acting white for same”: In-person and online/app-based discrimination exposure among sexual minority men. Sexual and Gender Diversity in Social Services, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/29933021.2024.2305461

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press. https://www.sup.org/books/sociology/theory-cognitive-dissonance

- Han, C. (2008). No fats, femmes, or Asians: the utility of critical race theory in examining the role of gay stock stories in the marginalisation of gay Asian men. Contemporary Justice Review, 11(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580701850355

- Johns, M. M., Pingel, E., Eisenberg, A., Santana, M. L., & Bauermeister, J. (2012). “Butch Tops and Femme Bottoms”?: Sexual Roles, Sexual Decision-Making, and Ideas of Gender among Young Gay Men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(6), 505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988312455214

- Moskowitz, D. A., & Hart, T. A. (2011). The Influence of Physical Body Traits and Masculinity on Anal Sex Roles in Gay and Bisexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 40(4), 835–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9754-0

- Padesky, C. A. (1994). Schema change processes in cognitive therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 1(5), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.5640010502

- Ravenhill, J. P., & de Visser, R. O. (2017). “It Takes a Man to Put Me on the Bottom”: Gay Men’s Experiences of Masculinity and Anal Intercourse. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 1033–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1403547

- Reigeluth, C. S., & Addis, M. E. (2021). Policing of Masculinity Scale (POMS) and pressures boys experience to prove and defend their “manhood”. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000318

- Vytniorgu, R., & Garcia-Iglesias, J. (2025). Bottom Shaming, Shame Anxiety, and Sexual Wellbeing. Lambda Nordica. https://doi.org/10.34041/ln.v.990

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. Norton. https://wwnorton.com/books/Narrative-Means-to-Therapeutic-Ends/