By Daniel Nkado.

It was October 2012. I was barely 20. I travelled to Umuahia to meet a man I had met on Manjam. Manjam was what Grindr is today—a space for connection, hope, and, unknowingly, danger. We chatted for months. And that Sunday, I finally decided to go visit him.

From the bus stop, he asked me to alight. I needed to pick up a bike (okada) to his place. I got into a small conversation with the bike rider — he told a funny story about why I needed to pay him more money. “Because I was a fine boy,” he said. We were instant friends. And then I mentioned the address I was going to. He became quiet and then asked to see the message. I showed him on my Nokia 6600 Symbian device.

He shook his head again and called me brother: “Delete these people’s numbers and run back home right now. Jump into the next bus now and start heading back to Awka. These people are robbers! They will strip you naked and take everything you have!”

As a gay man who grew up in Nigeria, my experience of kito is firsthand. It didn’t begin this way. What once were scattered humiliations and local jokes have hardened into organised extortion, blackmail and violence. Today, Kito is not only a practice of outing; it is a trade in fear that reaches across cities and preys on vulnerability.

To understand how this danger became named “Kito” and circulated, we must first look at the word itself.

The Cultural Texture of a Word

Some commentators point to the Hausa phrase ka sha kunya (a description of being shamed) as the origin of kito. However, that explanation misses the cultural texture and the actual route the word took into queer life. While the phonetic similarity is convenient, there is no historical or community-based evidence linking the term to Hausa usage.

The term ‘Kito’ originated in South-eastern Nigeria and spread with men who moved for work, school, and survival. Origin regions include Benin, Asaba, Onitsha, Awka, Enugu, Umuahia, Owerri, and Abakiliki. Men from these towns frequently travelled to the bigger cities—Lagos, Port Harcourt, and Abuja, etc.,— for work, school or running from hometown homophobia and carried with them local coded language. Those codes mixed with the slang of new cities; over the years, pan-regional terms emerged that worked across dialects and hid meaning from outsiders. In time, kito became the shorthand for both the practice and the people targeted by it.

The literal origin of the name is important because it reveals how ordinary life became a slang laden with menace. Kito began as the name of chunky, Dunes-style sandals we wore in primary school. Mothers bought them because they were durable and would stretch with growing feet. Children mocked their clunky look and the loud clack they made on cement floors. You could hear someone coming by their kito sandals, and the name stuck.

The sound was hard to miss, and soon, its ridicule turned into a queer slang: ‘Kito.’

From In-House Lingo To Criminal Enterprise

Language shifted from object of insult to tactic. Within queer circles, we developed a coded vocabulary so complete that two of us could speak in public without outsiders understanding. Phrases condensed whole practices: “He wore me kito” meant someone tried to out me; “He wore kito in that compound and had to move out” described forced relocation after suspicions rose. We used terms like “sand shoes” to flag particularly dramatic scandals.

Sand Shoes = Premium Kito

At first, the threat of kito was both a comic and coercive tool within queer networks. Effeminate men—loud, visible, defiant—were often labelled kito. Sometimes they weaponised the label themselves: a cheated partner might return with friends in flamboyant dress to publicly shame a lover who had been unfaithful. Those acts were usually confined to towns and cities where networks and anonymity made spectacle possible. Bringing kito drama into rural communities was almost unheard of; the stakes there could be fatal.

The Dark Mutation of Kito

What shifted over the last decade is scale and actors. Where kito had been a tactic used mainly within queer circles, non-queer people, often local gangs and opportunistic criminals, began to adopt it as a scheme. Strangers posing as dates arranged meetings through apps or social profiles, and then lured men to meet. Videos, screenshots, and threats turned into currency. Demands for ‘saving face’ money, bribes, or large sums for silence became routine. Local gangs organised the practice into a systematic, profitable enterprise.

There were whispers that it was gay people who introduced the idea to the dangerous street boys they were sleeping with. This angle—whether true, exaggerated, or weaponised—I can’t tell for certain. But I have always understood that being oppressed didn’t make us perfect. I also know that people can do disappointing things to survive. Life was harder for the ordinary Nigerian gay boy anyway.

The consequences are grim. Kito is not just shame; it is theft, kidnapping, violence, and death. Men have been robbed and beaten for small amounts; others have disappeared after being lured. For survivors, the trauma is both personal and social: the fear of exposure, the practical losses, the sense that there is nowhere safe to turn. Older men, those with families or public reputations, are especially vulnerable because the cost of exposure is high.

To this day, I still struggle to visit a date. If they’re not coming to my house, we might as well never meet.

We adapted survival tactics. Many kept “vex money” — emergency cash to take a bus home if a date turned sour. We learned to vet profiles, meet in public, and travel with friends. But these are imperfect shields against people who now use surveillance, fake identities, and coordinated violence.

An echoed warning: If you’re going where there is a possibility of kito, wear sneakers. You don’t wear kito to a kito!

It has a deeper meaning.

Stigma and Scarcity: An Ugly Intersection

Kito also reveals how shame and economics intersect. The practice works because of societal homophobia that makes exposure a credible threat. It prospers where legal protections are absent and where social safety nets for queer people are thin or nonexistent.

For many victims, being “outed” can lead to job loss, eviction, familial rejection, and even physical violence, making the price of silence—the extortionate demand—seem like the lesser of two evils. When laws fail to protect LGBTQ+ people from discrimination in employment, housing, and public life, and when community resources, mental health services, or emergency housing are unavailable to them, victims of kito are left with no safe recourse. Their economic vulnerability—often a consequence of systemic marginalisation—is weaponised against them. The lack of a stable financial and social foundation ensures that the threat of public shame carries maximum economic and personal damage.

That is why addressing kito calls for more than advice on safe dating: it requires community rapid-response networks, safer digital practices, legal advocacy, and public pressure to keep predators accountable.

Conclusion

This essay is part record and part caution. Tracing kito back to South-eastern roots and to a clumsy school sandal is not a nostalgic exercise; it shows how ordinary objects and words can be repurposed into tools of harm when prejudice and opportunity meet. Naming origins matters because it centres the communities who first named and resisted this practice.

Many of us survived, but we also lost many. Some didn’t die but couldn’t continue living either. Kito began as mockery, became slang, and finally mutated into a trade in humiliation. For many Nigerian queer people today, it is among the deepest sources of collective trauma.

We need stories, solidarity, and systems that treat those harms as the crimes they are, not as inevitable gossip or private shame. Our survival depends on our collective voice.

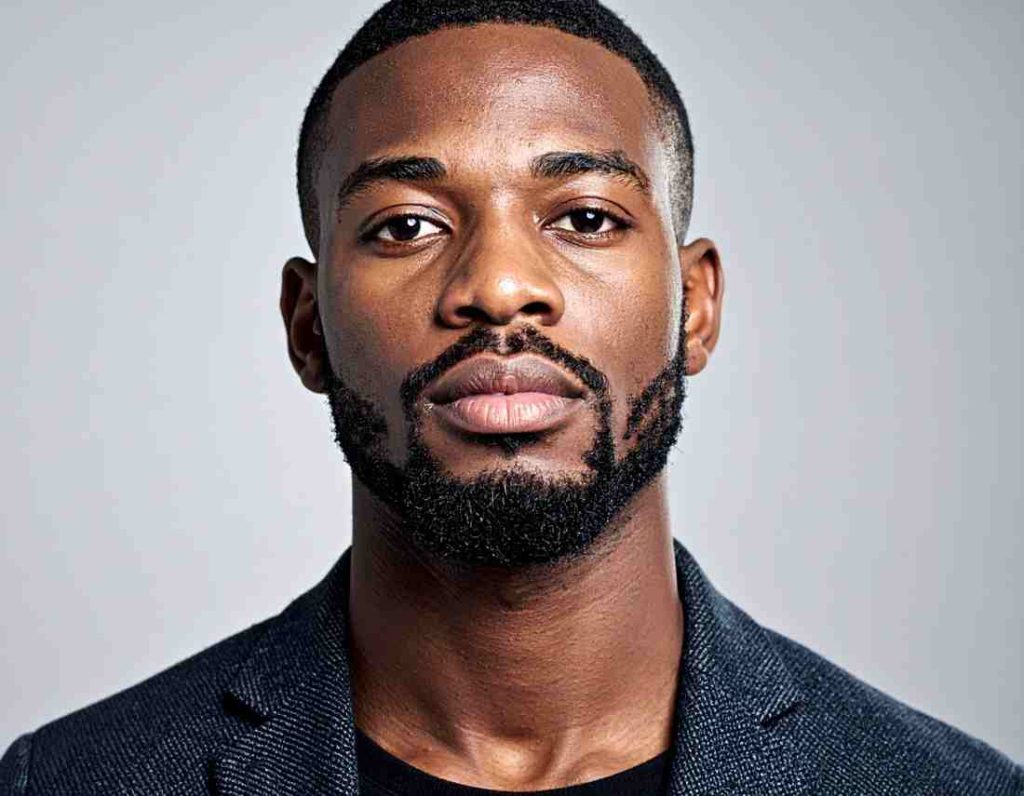

Daniel Nkado is a Nigerian writer, editor, and author best known as the founder of DNB Stories Africa, a digital platform covering Black stories, lifestyle, and queer culture.