Sex is supposed to be a moment of connection—where you are fully in your body, fully feeling rather than thinking. But sometimes, especially under pressure, your mind flips into “observer mode.” You stop being in the moment and mentally detach to begin watching yourself from the outside: checking angles, monitoring performance, and worrying about how you are being perceived.

This experience is called spectatoring. It is a term introduced in early sex-therapy literature to describe self-monitoring that kills arousal and interrupts pleasure (Titchener, 1971)[8].

While anyone can experience this, Black gay men often face a unique set of layered social stressors that fuel it. This isn’t about biology or personal weakness. It is about how our environment shapes our ability to relax, even in intimate moments.

🚨Important Context: At the time of publishing this article, there is currently no large-scale data giving a specific “percentage” of Black gay men who experience spectatoring compared to other groups. However, there is strong evidence that the conditions that cause spectatoring—anxiety, cognitive distraction, body surveillance, and stigma—are statistically more prevalent in the lived experience of Black sexual minority men due to compounded minority stress (English et al., 2021)[5].

This article explores the causes of spectatoring, including culturally relevant perspectives, and offers evidence-based, actionable steps to help Black gay men reclaim pleasure and full presence.

What is Spectatoring?

As earlier mentioned, spectatoring involves mentally stepping out of your body during sex to observe and evaluate your performance and appearance. It creates a “third-person” perspective, almost as if you are performing for a camera rather than sharing intimacy with a partner.

A. Mental Signs:

Internal dialogue during spectatoring often sounds like:

- “Do I look good from this angle?”

- “Am I performing the way he expects me to?”

- “Is my body ‘correct’ for this role?”

- “Is he judging me right now?”

In psychological terms, this is known as cognitive interference. These are anxiety-driven thoughts that steal your attention away from erotic cues (touch, sound, sensation), making it physically difficult to maintain an erection or reach climax (Barlow, 1986)[2].

B. Common Physical Signs of Spectatoring:

Spectatoring is a shift from experiencing to evaluating that manifests physically in the following ways:

- Muscle Guarding:

- You are physically “holding it together,” often with a clenched jaw, tight thighs, or shoulders raised toward your ears.

- Shallow Breathing:

- Instead of deep, rhythmic breaths that fuel arousal, you might find yourself taking short, quick breaths or holding your breath entirely.

- “Performative” Movement:

- You stop moving naturally and start moving mechanically—doing what you think you should do rather than what feels good.

- Numbness or Arousal Drop:

- You might suddenly lose your erection or feel sensation vanish. This happens because your brain has diverted blood flow and focus away from your genitals and toward your anxiety.

- Eye Aversion:

- You avoid eye contact, not because you are shy, but because you are trying to hide the fact that you have “checked out.”

🚨 While these signs are often linked to anxiety-related behaviours like spectatoring, they are not conclusive indicators. They can also stem from entirely different causes. For example, avoiding eye contact isn’t always about anxiety — it may reflect shyness, overstimulation (common with ADHD), or even cultural norms around respect. Context is essential; the real measure is the internal driver: is the avoidance motivated by intense pleasure or fear of judgment?

Why Spectatoring Can Hit Black Gay Men Harder

Spectatoring can be understood as a type of performance anxiety. To address the issue, it’s essential to identify the source of this anxiety. For many Black gay men, the pressure does not originate in the bedroom, but rather comes from the burden of external expectations that is carried into the room from outside.

Most common causes of anxiety and spectatoring behaviour in Black gay men:

1. Racialised Sexual Stereotypes

Black gay men are frequently boxed into rigid sexual scripts. Society often projects myths onto Black bodies, assuming they must always be dominant, hypersexual, or “built” a specific way (good examples are the “BBC” and “Mandingo” tropes).

In an intersectional study examining culturally circulating sexual stereotypes about Black men who have sex with men, participants described a dense overlap of racial and sexual-orientation assumptions (Calabrese et al., 2018)[3].

When you feel pressured to embody a script to be desirable, you naturally start monitoring yourself: Am I matching the fantasy? That mental checking is the definition of spectatoring.

2. The Impact of Minority Stress

Minority Stress Theory explains that chronic prejudice and discrimination create a constant state of high alert in the body. When you move through the world anticipating discrimination, your nervous system stays ready to defend itself (hypervigilance).

In this case, switching from “survival mode” to “pleasure mode” will require more time and effort. Even in a safe bedroom, your body may remain guarded, leading to self-monitoring.

3. Sexual Racism and ‘Preference’ Culture

In the world of fast-paced dating apps like Grindr, Jack’d, and Scruff, race is often used as a means of filtering.

This could manifest as:

- Blatant rejection—”No Blacks”

- Fetishisation—”Want to be my first BBC?”

- Being treated as a category rather than an individual—”DDF” (drug and disease-free), “Clean”, “no fats”, “DL only”.

Some categories often framed as “preferences” on dating apps actually mask underlying biases or discrimination. Research shows that sexual racism in these spaces can create long‑term mental vigilance, prompting individuals to constantly scan for bias and adjust their behaviour to minimise harm. Scholars describe how these coping and “compensation” strategies can spill over into sex as self‑surveillance, tension, and performance anxiety (Callander et al., 2015[4]; Ang et al., 2021)[1].

4. Objectification in Queer Spaces

While queer spaces are meant to be safe havens, they can also be intensely critical of bodies and sexual performance.

Studies suggest that in some gay communities, men of colour are often tokenised—desired through stereotypes and pushed into preset “roles,” rather than seen as whole people (Teunis, 2007)[7].

Navigating these unspoken standards of assessment creates additional pressure for Black gay men, compounding their inability to relax, trust, and feel fully seen in intimate moments.

Watching yourself in a mirror vs Spectatoring

The common practice of watching yourself in a mirror during sex isn’t automatically spectatoring. If your reflection turns you on and helps you stay present, that’s visual engagement—not anxiety.

It becomes spectatoring, however, when the mirror shifts from a reflection of pleasure to critique. If seeing yourself makes you tense up, adjust your posture, suck in your stomach, or worry about how you look or being looked at, the mirror has started feeding self-monitoring (the kind of cognitive distraction that can pull you out of arousal, causing spectatoring). Learning to tell the difference between admiring yourself (confidence) and surveilling yourself (anxiety) is a powerful step toward reclaiming sexual presence.

Tip: If mirrors trigger self-judgment, try covering them or angling them away for a while. Removing the sense of an “audience” can make it easier to drop back into your body.

How to Reduce Spectatoring and Reclaim Pleasure

If this feels familiar, remember: nothing is wrong with you. What you’re feeling is a stress response.

These research‑informed practices can help you reconnect with your body.

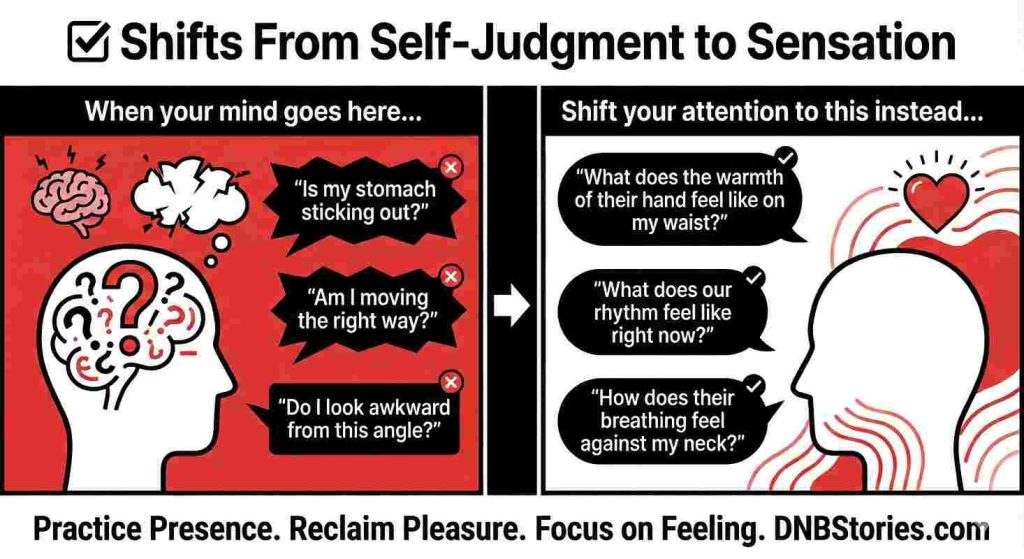

1. Switch from ‘Performance’ to ‘Sensation’

Spectatoring thrives on self-judgement (grading your performance). To counter it, shift your focus from trying to “score higher marks” to tactile sensation—touch, breath, and sensation.

- The Shift: Instead of: “Is my stomach sticking out?” Shift to: “What does the warmth of their hand feel like on my waist?”

- The Science: This is the basis of “Sensate Focus,” a core technique in sex therapy that removes the goal of orgasm and prioritises touch to reduce performance anxiety (Linschoten & Weiner, 2016)[6].

2. Prioritise safe spaces where communication is easy

Spectatoring loses power when it is spoken out loud. If you feel yourself drifting into your head, try saying:

“I’m getting a little in my head right now. Can we slow down/switch positions so I can get back in the moment?”

Choosing an emotionally supportive partner matters. They help create emotional safety through fostering a non-judgmental space where you don’t feel watched or graded. This helps you relax, connect deeper, and stay fully present.

3. Challenge ‘Roles’ and Expectations

If you feel you must top, must be aggressive, or must act a certain way because you are Black, pause for a moment and ask: Who really benefits from this belief of mine?

Stereotypes are social scripts designed to confine people in boxes (like a “lab rat” in a cage), not biological directives. You have the control to define sex on your own terms—soft, passive, dominant, or fluid—and choose partners who complement your energy, not increase pressure.

4. Find Your Path / Find You — and Stay With It

Protect your peace by choosing spaces — online and offline — that affirm Black queer humanity rather than fetishising it. When you limit your exposure to environments where sexual racism is normalised, your baseline anxiety naturally decreases. With less vigilance in your system, it becomes easier to relax, trust, and feel present when you do connect with someone.

5. Honour Your Nervous System

Your body is always communicating with you. Pay attention to the cues that tell you when you feel safe, open, and grounded—and when you feel tense, hyperaware, or disconnected.

Remember: These signals are not overreactions; they are information.

When you honour what your nervous system is telling you, you make choices that protect your peace and deepen your pleasure. This might mean:

- Slowing down the pace.

- Taking a break to breathe.

- Leaving or stepping away from situations or people who trigger anxiety or self‑doubt.

Listening to your body is not avoidance—it’s self‑respect.

Final Thoughts

Spectatoring is not a failure; it is often a stress response from a mind trying to protect you in a judgmental world. But presence is possible.

If spectatoring is persistent, distressing, or linked to past trauma, consider speaking with an LGBTQ-affirming and culturally competent sex therapist. You deserve support that understands and prioritises the full context of your life, not just the symptoms.

References

- Ang, M. W., Ching, J., & Lou, C. (2021). Navigating sexual racism in the sexual field: Compensation for and disavowal of marginality by racial minority Grindr users in Singapore. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 26, 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab003

- Barlow, D. H. (1986). Causes of sexual dysfunction: The role of anxiety and cognitive interference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.54.2.140

- Calabrese, S. K., Earnshaw, V. A., Magnus, M., Hansen, N. B., Krakower, D. S., Underhill, K., Mayer, K. H., Kershaw, T. S., Betancourt, J. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2017). Sexual stereotypes ascribed to Black men who have sex with men: An intersectional analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(1), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0911-3

- Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(7), 1991–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0487-3

- English, D., del Río-González, A. M., Tolan, E. A., Vaughan, A. S., Griffith, D. M., & Bowleg, L. (2021). Intersecting structural oppression and Black sexual minority men’s health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(6), 781–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.12.022

- Linschoten, M., & Weiner, L. (2016). Sensate focus: A critical literature review. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 31(2), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2015.1127909

- Teunis, N. (2007). Sexual objectification and the construction of whiteness in the gay male community. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(3), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050601035597

- Titchener, J. L. (1971). Human sexual inadequacy. By W. H. Masters and V. E. Johnson. Little, Brown, Boston. 487 pp. 1970. Teratology, 4(4), 465–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/tera.1420040411