Introduction—Rethinking the Western Closet Paradigm

Western culture often portrays “coming out of the closet” as a transformative experience for gay men—a narrative promoted by the media, popular culture, and mainstream queer theory, which frames the public revelation of one’s sexuality or the event of leaving the closet as the ultimate act of courage, essential for personal freedom and authentic living.

While “coming out” can offer significant benefits, treating it as a universal necessity ignores the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals from different backgrounds—particularly Black gay men and those from non-Western or communal cultures—whose journeys to identity, safety, and acceptance may not involve, or even welcome, public declarations or spectacle (Wang, 2017)[8].

This article explores why Black gay men often do not “come out” like their white counterparts, moving beyond the binary of secrecy versus revelation to introduce a new framework: the Model of Dynamic Disclosure (DnD).

Coming Out is Different for Black Gay Men

Multiple scholarships and community lived experiences support the view that “coming out of the closet” is not a one-size-fits-all concept.

For Black gay men, whether in Africa or the diaspora, sexual identity often takes a more complex form, shaped by the intersectional pressures of race, family expectations, and survival. These converging factors make the standard Western “coming out” narrative inadequate for capturing their unique experiences and realities (Baatjies-Okoudjou, 2023)[1].

The Racial Limitations of the Binary Closet Paradigm

The “closet paradigm”—the idea that LGBTQ+ life is a simple split between being “in” (hidden) or “out” (open)—has shaped Western queer theory and activism for decades. While this framework, popularised by theorists like Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (1990)[7], has helped many understand the journey to self-acceptance, many writers have disagreed with its universal positioning for all gay men.

Author Marlon B. Ross (2005)[6] specifically argues that it’s rooted in white, middle-class Western experiences, which doesn’t fully capture the realities faced by Black gay men in the United States.

A Global Coming-Out Model for Every Black Gay Man

Ross’s critique of the binary Western closet-paradigm powerfully explains how race and sexuality intersect within the U.S., but—like much of the discourse around the subject—it doesn’t fully account for Black queer life beyond America. Scholars such as Keguro Macharia[4] offer more Africa-centred approaches, like “Networks Over Labels,” suggesting a shift from “Are they out?” to “How do they connect?” Yet the global reality remains complex: Black gay men across Africa, the Caribbean, and the wider diaspora navigate distinct legal, cultural, and economic pressures that demand more nuanced frameworks.

Bridging these gaps requires a truly global Black queer theory that replaces the rigid ‘in/out’ identity binary with an understanding of ongoing negotiation around identity, safety, belonging, and survival. Crucially, such a theory must also recognise strategic silence, indigenous queer networks, and communal obligations as valid and authentic expressions of queer life (Huang, 2021)[2].

Key Points:

- The Western “closet paradigm” doesn’t fit all Black gay men’s experiences.

- In Africa and the diaspora, coming out can be risky due to legal, cultural, and economic pressures.

- For many, silence is a survival strategy—not a lack of courage.

- Indigenous queer networks and family obligations shape identity differently across contexts.

The Solution: The Model Built On Negotiation

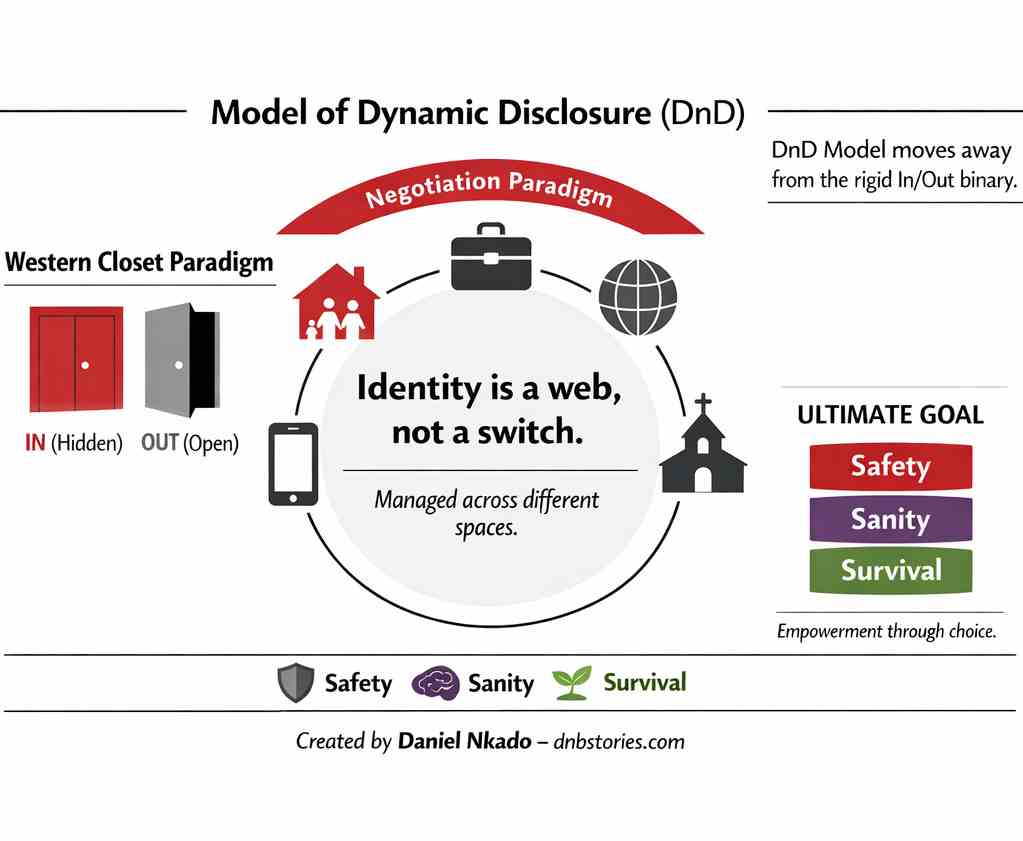

The negotiation paradigm views queer identity as a fluid, context-dependent process, involving ongoing management of relationships, risk, and visibility across varied spaces (family, work, faith, community, online). This contrasts with the Western closet paradigm, which frames disclosure as a rigid in/out binary.

In Black queer theory, this approach resonates with E. Patrick Johnson’s Quare Theory (2001)[3], which emphasises identity as shaped by community, culture, and negotiation rather than universal norms. Extending this, Daniel Nkado’s Dynamic Disclosure Model (DnD) formalises negotiation as a framework, portraying identity as a web managed differently across contexts to achieve safety, belonging, and authenticity.

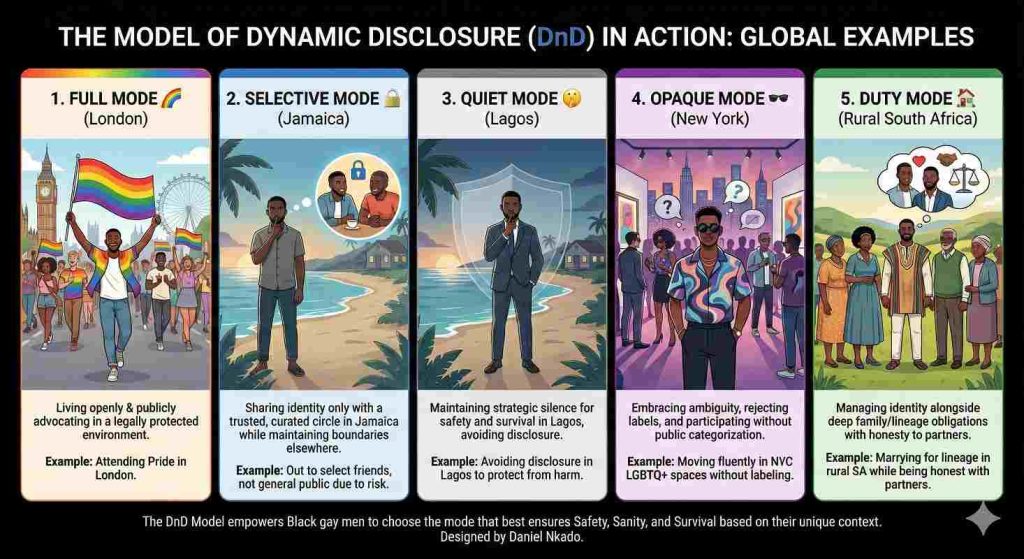

The model presents a five-mode framework for navigating privacy, safety, and authenticity beyond the rigid “coming out” binary. Grounded in cultural realities and survival, it offers practical strategies for living truthfully without risking everything—especially for Black queer life across Africa and the diaspora.

Introducing the Model of Dynamic Disclosure (DnD)

Developed by Daniel Nkado, the DnD Model recognises that identity disclosure is not a one-size-fits-all journey. Instead, it offers five flexible modes, empowering individuals to tailor their approach to suit their specific safety, relationship, and cultural needs.

Five Modes of the DnD Model:

- Full Mode: 🌈 Openly living as gay in all areas of life.

- Selective Mode: 🔒Sharing identity only with trusted individuals or in safe spaces.

- Quiet Mode: 🤫 Maintaining privacy and silence for safety or personal reasons.

- Opaque Mode: 🕶️ Embracing ambiguity or non-labelling, allowing for privacy and protection.

- Duty Mode: 🏠 Balancing personal identity with family or community responsibilities.

1. Full Mode 🌈

The “Western Ideal” Adapted—Living openly and authentically as gay in all spheres—home, work, community, and digital spaces.

- How it works: You are “out” to everyone and can participate visibly in LGBTQ+ advocacy.

- Who it suits: Those living in legally protected environments with strong support networks and economic and emotional independence.

- Benefits: Maximises self-expression and political visibility.

- Risk: Can be dangerous in hostile environments; may need careful planning if relationships or employment could be affected.

2. Selective Mode 🔒

The “Invited In” Approach—Sharing your identity strictly with trusted individuals or within curated safe spaces.

- How it works: You bypass a public announcement in favour of “inviting in” specific friends or siblings. Participation in LGBTQ+ life is limited to private or online communities.

- Who it suits: Individuals in mixed environments who value authentic connection but cannot risk full exposure.

- Benefits: Balances mental health (connection) with physical safety.

- Risk: Requires a good sense of judgment to determine who to tell and where.

3. Quiet Mode 🤫

The “Open Secret” / Strategic Silence—Maintaining privacy regarding sexuality to prioritise safety, comfort, or cultural harmony.

- How it works: You do not verbally disclose to anyone, or only to a partner. You may use coded language or silence to navigate social situations. This is not “hiding” in shame, but a refusal to engage with the public gaze.

- Who it suits: Those in environments where disclosure carries legal, economic or physical threats.

- Benefits: Reduces risk of negative consequences (harm or exclusion).

- Risk: Isolation and the pressure of maintaining secrecy.

4. Opaque Mode 🕶️

The “Right to Opacity”—Embracing ambiguity. A refusal to label oneself or explain one’s dynamics to the outside world.

- How it works: You may present as single or ambiguous. You exist in queer spaces without adopting specific terminology. You assert the right not to be categorised.

- Who it suits: Those in unpredictable environments or individuals who find Western labels reductive or colonial.

- Benefits: Offers a shield against categorisation/labelling while allowing fluid movement between different social worlds.

- Risk: May be misunderstood by others.

5. Duty Mode 🏠

The Communal Negotiation—Balancing personal identity with deep-seated family, lineage, or economic responsibilities.

- How it works: You may fulfil societal expectations (such as marriage or procreation) to maintain family lineage, while privately acknowledging your sexuality.

- Who it suits: Individuals in collectivist cultures where survival is tied to the extended family (“The Village”) or where disclosure can break family stability or economic support.

- Benefits: Preserves vital support systems and cultural values.

- Risk: May require emotional complexity and careful communication to safely navigate ethical negotiation and decision-making.

Crucial Note: To be healthy, Duty Mode must prioritise honesty with immediate partners (such as a spouse or co-parent). This transparency is necessary to prevent harm and separates the mode from other damaging, deceptive behaviours.

A Critical Note on Mixed-Orientation Marriages

Duty Mode recognises that some Black gay men marry women due to culture, safety, or survival—but it is not an endorsement of deception. When a spouse later discovers hidden sexuality, the harm often takes the form of betrayal trauma, driven mainly by the secrecy and broken trust, and not the orientation itself. The DnD Model aims for harm reduction, encouraging honest, negotiated arrangements that respect everyone’s agency and dignity.

A Note on ‘DL’ vs ‘Out’

Being “DL” isn’t the opposite of being out—it’s about discretion for safety, cultural, or personal reasons, not denial. Historically, DL described Black men managing risk in hostile environments, not hiding identity (Robinson, 2009)[5]. Over time, media and app culture distorted DL into a term tied to secrecy, shame, and performative masculinity.

In the DnD Model, DL behaviour aligns with Quiet Mode or Selective Mode, depending on how trust and visibility are managed. Quiet Mode reframes privacy as agency—a deliberate, values-based choice shaped by context and safety.

DL? Nah—I’m not hiding, I’m just in Quiet Mode for now.

How to Use the DnD Model Safely

- Assess Your Terrain: Evaluate your environment—legal risks, financial dependence, family expectations, religious exposure, and workplace climate. Your safety profile shifts with context.

- Rotate as Needed: You’re not fixed in one mode. You might be in Full Mode online, Selective Mode with friends, Quiet Mode at work, and Duty Mode with family. Adapt as settings change.

- Reject the Hierarchy: No mode is “braver” or “better.” The right mode is the one that keeps you safe, grounded, and supported—without jeopardising your future. Authenticity means living true to yourself, not performing for society.

- Prioritise Honesty and Care: In Duty Mode, focus on harm reduction. Protect trust, practise informed consent, and avoid choices that may cause another person unnecessary harm.

Conclusion

Black gay men do not have to “come out” like other races because their survival, joy, and identities are forged in a different fire. The closet paradigm, while a useful tool for some, is historically specific and racially limited.

Recognising the validity of the DnD Model—from the “open secret” of Quiet Mode to the ethical negotiation of Duty Mode—allows us to move toward a more inclusive understanding of LGBTQ+ life.

It reminds us that authenticity is less about announcements and more about genuine living.

References

- Baatjies-Okoudjou, E. (2023). Explorations of black gay men’s experiences in their coming-out process. University of Johannesburg. https://ujcontent.uj.ac.za/esploro/outputs/graduate/Explorations-of-black-gay-mens-experiences/9942602507691

- Huang, S. (2021). Alternatives to Coming Out Discourses. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.1179

- Johnson, E. P. (2001). “Quare” studies, or (almost) everything I know about queer studies, I learned from my grandmother. Text and Performance Quarterly, 21(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462930128119

- Macharia, K. (2019). Frictions of Intimacy across the Black Diaspora (Vol. 11). NYU Press; JSTOR. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1jhvntn

- Robinson, R. K. (2009, May 27). Racing the Closet. SSRN.com. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1410871

- Ross, M. B. (2005). Beyond the Closet as Raceless Paradigm. Black Queer Studies, 161–189. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822387220-010

- Sedgwick, E. K. (1990). Epistemology of the Closet. University of California Press. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/research/centres/gender_and_feminist_theory_group/14_eve_sedgwick_introduction_to_epistemology_of_the_closet_1990.pdf

- Wang, P.-H. (2017). Out of the country, out of the closet: Coming out stories in cross-cultural contexts. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328017640_Out_of_the_country_out_of_the_closet_Coming_out_stories_in_cross-cultural_contexts