By Daniel Nkado.

Why do some gay men command the runway in heels while others play football like the game was designed for them?

Anyone who’s met a range of gay men knows there’s no single ‘type.’ Some gay men are flamboyant, others macho, and plenty fall somewhere in between.

This diversity sparks a fascinating question: what drives masculine or feminine behaviour in gay men? Let’s dive into the science, the psychology, and the surprising truths in between.

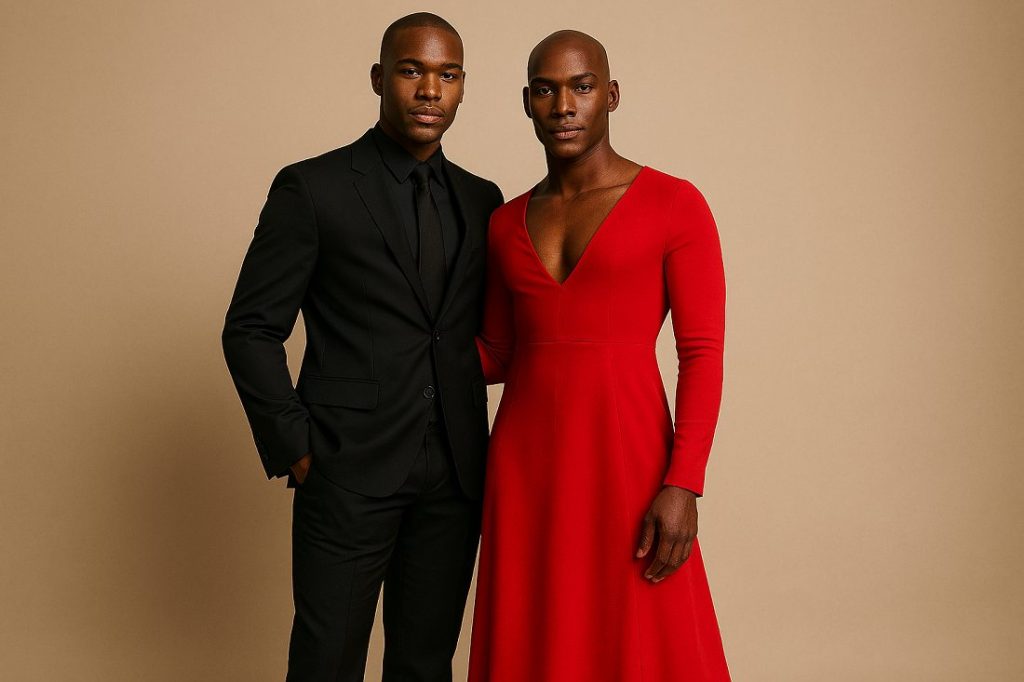

What are ‘fem’ and ‘masc’?

“Fem gay men” refer to gay men who present with traits traditionally associated with femininity or women. The term feminine-presenting man can also be used to describe a fem gay man.

When people describe a man as ‘feminine,’ they often point to traits society associates with women, like a softer voice or expressive gestures, or interests like fashion or pop culture, instead of football.

Masc gays, on the other hand, are gay men who present themselves in a traditionally masculine way. Their demeanour, style, and behaviours align with society’s typical ideas of masculinity, whether by default or by conscious choice.

Gender Identity vs. Gender Expression

Being feminine or masculine is about gender expression, not sexual orientation.

For clarity, here’s a breakdown of key concepts:

| Concept | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity | Who you are — your internal sense of being male, female, both, or neither. | A trans person whose gender identity is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. |

| Gender Expression | How you present yourself to the world — (e.g., through clothing, body language, or tone of voice). | Being masculine, feminine, or androgynous. |

| Sexual Orientation | Who you’re attracted to romantically or sexually. | Being gay, straight, bisexual, or pansexual. |

Not all gay men are feminine, and not all feminine men are gay. Still, studies show that gay men, on average, are more likely than straight men to express some feminine traits. Which leads us to the big question — why?

1. Role of Biology (Nature)

The story begins with biology. Scientists have established that a person’s gender expression is a result of a complex mix of both biological factors (e.g., prenatal hormone levels) and non-biological factors (culture, society, and personal choices).

The biological foundation can lean masculine or feminine in different people, regardless of who they’re attracted to, but it does not rigidly direct expression. Keep in mind that feminine traits also appear in some heterosexual men, just less commonly and with different patterns.

Research by Gerulf Rieger et al. (2008)4 analysed old home videos of children, before anyone knew who’d grow up gay or straight. Boys who later turned out gay often showed more “feminine” mannerisms as kids — things like how they ran, talked, or played (childhood gender nonconformity).

Other studies, like those by Bailey and Zucker (1995)1, also support that boys who later identify as gay in adulthood often exhibit gender-nonconforming behaviours in childhood, such as unique ways of moving or playing. Large cohort studies2, like the Avon Longitudinal Study3, also found correlations between such behaviours and adult homosexuality, though causation isn’t clear.

The brain may hold the answer

Scientists think the mix of hormones we’re exposed to in the womb — especially testosterone — can subtly shape how our brains develop, and these shifts may predispose individuals toward certain behaviours or preferences. For example, higher prenatal testosterone exposure is linked to more stereotypically masculine behaviours in both males and females.

But these prenatal influences are neither absolute nor deterministic. The final expression or behaviour comes from a complex interaction between biological and cultural factors, as well as the individual’s personal choices and experiences.

Gender expression is flexible; Orientation, not so much

Research clarifies that the biological influences on gender expression are less fixed than those underlying gender identity and sexual orientation, which are often more stable due to their stronger ties to early brain development and genetic factors.

This flexibility means individuals — including gay men — can consciously adapt how they express themselves, from choice of clothing to mannerisms, in ways that reflect their personality, respond to social feedback, or align with cultural norms, regardless of their biological predispositions.

2. Role of culture and environment (Nurture)

Gender expression has biological roots, but this does not dictate the overall outcome. Culture and environment heavily influence how individuals choose to express their gender.

A boy who acts feminine might be teased, scolded, or told to “man up.” Some learn to hide their softness; others grow up and decide to embrace it loudly and proudly.

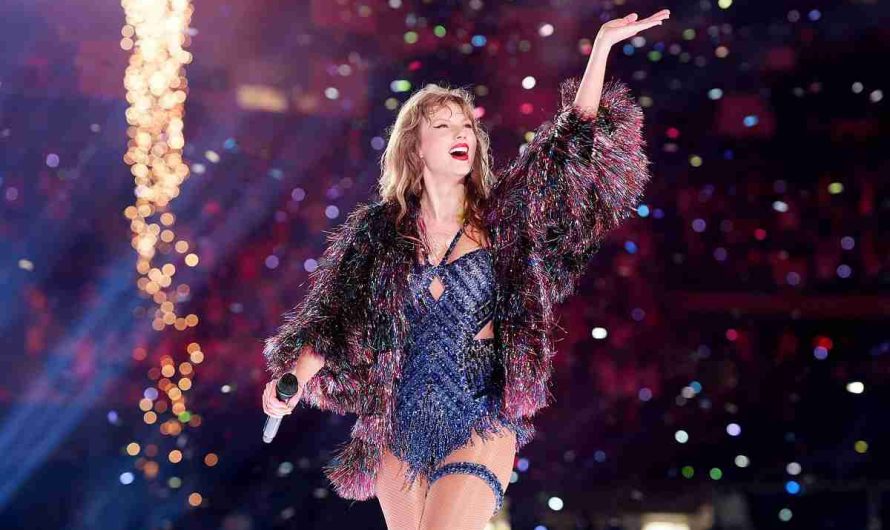

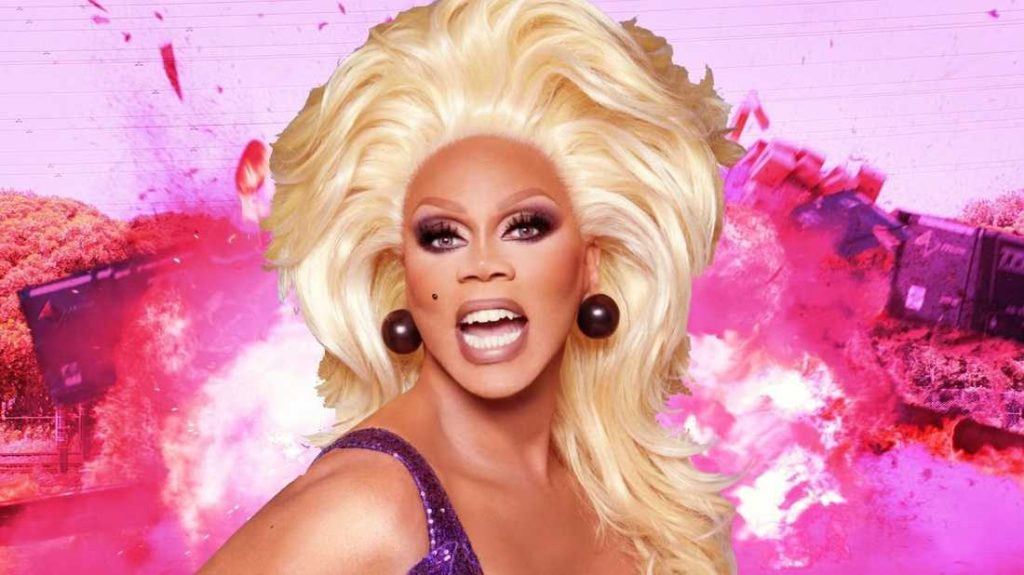

In safe or open environments — especially within queer communities — feminine traits can be celebrated. That’s how styles like drag, ballroom culture, and the whole “camp” aesthetic became powerful forms of self-expression and pride for some gay men.

Culture polices gender expression by providing the basic interpretation of behaviour itself. Gender is, in part, a social construct, meaning that what is considered “masculine” or “feminine” is not fixed or universal but varies across different societies and historical periods.

In the Igbo region of Nigeria, for instance, effeminacy was once celebrated but later stigmatised following colonial influences.

Despite the strong influence, culture alone does not singularly determine an individual’s resulting expression. People can still consciously choose to conform to or resist cultural gender norms.

3. Gay men have some control over their behaviour

While biology and culture set the stage, personal agency —the capacity to make choices and act on them— allows gay men to shape their gender expression, whether by embracing, suppressing, or blending traits.

Some gay men embrace their feminine traits. Others suppress them to project a more traditionally masculine behaviour. Some discover a mix of both that feels right for them.

The Verdict: What drives masc and fem behaviour in gay men?

As now unravelled, masculine or feminine behaviour in gay men is the result of a complex mix of biological factors (nature), social and cultural influences (nurture), and personal decisions (choice).

| Factor | Definition | Role in Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Nature (Biology) 🧬 | Innate traits (e.g., temperament) | Provides a blueprint for expression, like voice or gestures. |

| Nurture (Environment) 🌍 | Culture and society | Shapes expression through pressure or acceptance. |

| Personal Choice (Agency) ✨ | Individual decisions | Determines whether to embrace, suppress, or blend traits. |

In summary:

Some gay men fully embrace their feminine side, living as vibrant “femboys” or “queens.” Others tone it down for safety or acceptance. Some naturally embody masculinity, while others perform it strategically, adopting “macho” personas. Each path reflects a unique balance of biology, culture, and choice.

Perfecting the masculine act often starts early!

For some gay men, especially those who noticed in childhood that their expressive gestures or feminine-leaning behaviours drew attention or criticism, the conscious shift toward a masculine persona begins early.

This early performance, enabled by the brain’s high neuroplasticity in childhood, can become a deeply ingrained habit, feeling almost natural by adulthood, though it may carry an emotional cost.

Gay men and the performance of masculinity

Under stricter pressure, some gay men, particularly those with more obvious feminine traits, may overcorrect, that is, adopt a hypermasculine or “macho” persona. They do this by exaggerating traits like dominance, aggression or loudness as a defence against judgment and stigma.

This behaviour, known as masculine overcompensation, can also be triggered as a defence against past accusations of being gay or unmanly.

In some gay subcultures, this behaviour is also called “mascing”—a slang term for the strategic performance where gay men exaggerate masculine traits and suppress feminine ones.

Some gay men with naturally expressive or feminine traits often adopt a macho persona as a defence mechanism.

Research suggests that overperformance of masculinity can be reinforced by environments that strongly stigmatise femininity, contributing to internalised homophobia as individuals navigate societal pressures that devalue their authentic selves.

Additionally, in the gay community, hypermasculinity or “macho performance” often attracts a high social currency—profiles boasting “macho” or “dom” traits on gay apps like Grindr attract more attention, creating another strong incentive for some gay men to adopt this behaviour.

Whether as a shield for hiding feminine traits or a strategy for boosting desirability, this overperformance can come at a significant psychological cost, contributing to anxiety, depression, and self-hatred.

Conclusion: There’s no wrong way to be you!

Whether embracing femininity, masculinity, or a mix of both, gay men navigate a unique path shaped by biology, culture, and conscious choice—proving there’s no one way to be authentically you.

True queer authenticity is found in celebrating every facet of a gay man’s expression, from understated masculinity to unapologetic femininity.

The goal here is personal liberation—the deliberate decision to embrace one’s authentic identity beyond community or societal pressures and cultivate self-worth through practices such as self-compassion, purposeful living, and community engagement, which empowers gay men to thrive authentically rather than merely cope or conform.

***

Daniel Nkado is a Nigerian writer, editor, and author, best known as the founder of DNB Stories Africa, a digital platform covering Black stories, lifestyle, and queer culture.

📚 Footnotes / References

- Bailey, J. M., & Zucker, K. J. (1995). Childhood sex-typed behaviour and sexual orientation: A conceptual analysis and quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.43

- Grueneisen, S., & Tomasello, M. (2017). Children coordinate in a recurrent social dilemma by taking turns and along dominance asymmetries. Developmental Psychology, 53(2), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000236

- Major-Smith, D., Heron, J., Fraser, A., Lawlor, D. A., Golding, J., & Northstone, K. (2023). The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC): a 2022 update on the enrolled sample of mothers and the associated baseline data. Wellcome Open Research, 7, 283–283. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.18564.2

- Rieger, G., Linsenmeier, J. A. W., Gygax, L., & Bailey, J. M. (2008). Sexual orientation and childhood gender nonconformity: Evidence from home videos. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.46