The Rise of Ancestral African Worship Among Gay Men

Across the African diaspora, a spiritual migration is taking place. Many Black queer men are moving away from religious spaces that have historically harmed or excluded them, turning instead toward African Traditional Religions (ATRs) for healing, empowerment and cultural reconnection.

Practices such as Hoodoo and Ifá centre African ancestral gods and deities—Oshun, Ogun, Shango, Ala, Ikenga, Amadioha—alongside community ethics and the wisdom carried through lived experience. These traditions are rooted in human relationships rather than rigid doctrines about gender or sexuality. For many Black gay men, this opens a doorway to a spiritual home that affirms identity rather than erasing it.

Still, stepping into these traditions can be intimidating for beginners who often ask:

- “Am I doing this correctly?”

- “Will the ancestors accept me as a gay man?”

- “Is this practice safe for me?”

This guide answers those questions with clarity and respect. It explores the foundations of Hoodoo and Ifá worship, and explains why they are inherently queer-affirming. It also provides a step-by-step manual for setting up an ancestral altar at home—without fear, perfectionism, or the need for expensive tools.

Understanding the Traditions: Hoodoo and Ifá

To practice effectively, it is helpful to understand the distinction between these two often-linked systems.

What is Hoodoo?

Hoodoo (often called conjure or rootwork) is an African American spiritual system born out of survival during the era of enslavement in the United States. It is a syncretic practice, blending West and Central African cosmologies with Indigenous American herbal knowledge and selective Christian elements.

Crucially, Hoodoo is not a religion; it is a spiritual folk practice focused on results. It emphasises ancestral reverence, spiritual work, and practical protection (Anderson, 2008)[2]. Its core features include:

- Ancestral Veneration: The belief that the dead play an active role in the lives of the living.

- Rootwork: The use of herbs, roots, minerals, and curios to influence outcomes.

- Resistance: A focus on justice, survival, and empowerment for the marginalised.

Because Hoodoo is adaptive, it has historically been a refuge for those pushed outside mainstream power structures—making it a natural home for Black queer people.

What is Ifá?

Ifá is a complete religious and spiritual system originating with the Yoruba people of present-day Nigeria and Benin. It encompasses a vast body of wisdom, divination systems, ethical teachings, and the worship of Orisha—divine forces of nature that govern human experience (Abímbọ́lá, 1997)[1]. Shango, Oshun, and Yemaya are all Orishas.

Are Hoodoo and Ifá Queer-Affirming?

Yes. It is vital to understand that the homophobia present in many modern Black communities is often a byproduct of colonialism and missionary Christianity, not pre-colonial African spirituality.

Many scholars note that pre-colonial Yoruba and Igbo societies did not operate with the rigid gender binaries imposed by the West. In fact, specific Orishas and spiritual roles historically transcended gender norms. Furthermore, contemporary practitioners and authors, such as Juju Bae, explicitly affirm LGBTQ+ people within Africana traditions. They emphasise that ancestors respond to sincerity, character (iwa), and ethical living, rather than heterosexual performance (Bae, 2022)[3].

IMPORTANT: Your queerness is never a barrier to ancestral connection. It is part of your lived truth — and truth is the foundation of all ancestor work. Maintaining a strong relationship with ancestral spirits requires choosing honesty in every moment. This commitment is essential and cannot be compromised (Hucks, 2012)[4].

Step-by-Step: How to Set Up an Ancestral Altar

An altar is a point of contact—a place to build a relationship, not a museum display. Start small, keep it simple, and allow it to evolve naturally.

1. Choose a Designated Space

Find a clean, low-traffic area in the house. This could be a shelf, the top of a dresser, or a small table. Avoid placing altars on the floor or near a toilet/bathroom, as these areas are considered energetically “lower” or unclean in many traditions.

2. Cleanse the Space

Before setting anything down, clean the surface physically. Then, cleanse it spiritually. You might say a prayer, sprinkle Florida Water (a cologne used in spiritual work), or burn frankincense. The intention is to clear away stagnant energy and invite clarity.

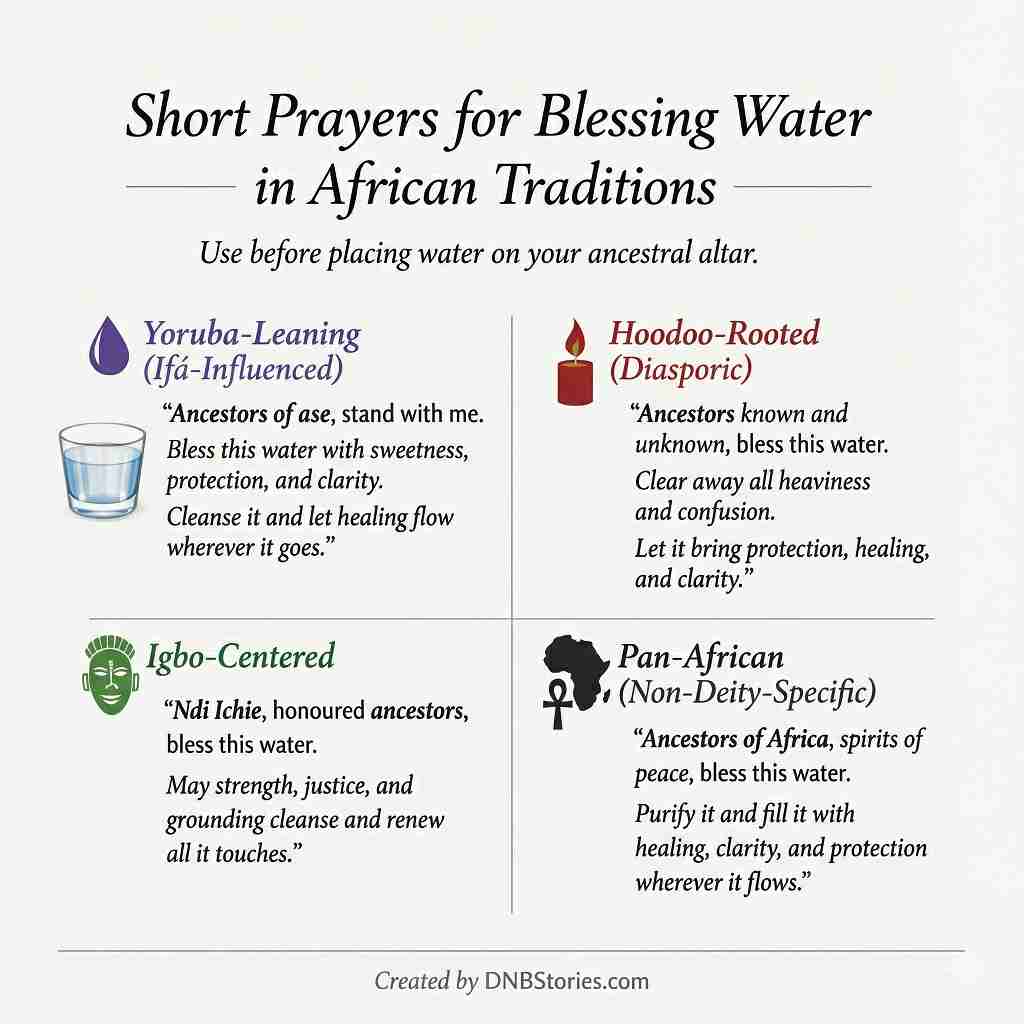

Another alternative to Florida Water is to prepare a home-made Blessed Water:

- Add salt to water in a clean, white bowl.

- Drop one or two Aidan fruits (Tetrapleura tetraptera), also called prekese or uhio in Nigeria/Ghana.

- Say a short prayer, inviting the good souls of the departed to cleanse and bless the water.

- Let it stay overnight if possible, and then transfer the blessed water into clean transparent bottles for use as required.

3. Lay a White Cloth

Cover the surface with a clean white cloth. In many African and diasporic traditions, white symbolises peace, elevation, and spiritual clarity. It creates a boundary between the sacred space and the mundane world (Karade, 1994)[5].

4. Add a Bowl of Clean Water

Water is the universal medium for spirit communication; it conducts energy. Place a white bowl of fresh, cool water on the altar. Change this water daily or weekly, as may be required, never letting it get murky or dusty.

5. Include Ancestor Representation

This allows you to focus your energy. You can use:

- Photographs of deceased family members (ensure no living people are in the photos).

- Obituaries or heirlooms.

- If you do not know your lineage: Write a simple note on paper, such as: “To my benevolent ancestors of blood and spirit who love, support, and protect me.”

6. Light a White Candle

A white candle represents the “light” of the spirit and your prayer. Light it when you are actively praying or spending time at the altar. Always practice fire safety.

7. Offer Food or Drink

Ancestors are treated as honoured guests. There are several options, but for longevity and hygiene, you can offer candies, white alcoholic spirits or dried nuts.

8. Honour the Four Elements

A balanced altar often represents the forces of nature:

- Water: The bowl of water.

- Fire: The candle.

- Air: Incense, cigar smoke, or simply your spoken words.

- Earth: Crystals, clear stones, flowers, or a bowl of clean soil.

9. Speak and Listen

The most important tool is your voice. Talk to them openly about your fears, joys, grief, and love. Then, sit in silence. Pay attention to your dreams, intuition, and emotions in the days that follow.

Tips for Your First Prayer

- Breathe: Before you speak, take three deep breaths. Ground yourself. You are not performing; you are having a conversation with family.

- Use Your Own Words: Speak naturally, even if you feel unsure or stumble. Don’t worry about sounding “correct” — your ancestors already know who you are. Focus on sincerity rather than perfect phrasing. Let your emotions guide your words; speak from the heart.

- Pour Libation: As you say, “I offer this drink,” tap the bottle lightly to signal your intention, or sprinkle a few drops onto the floor or ground as a gesture of sharing with the ancestors.

Benefits of Setting Up an Ancestral Altar for Black Gay Men

The ultimate benefit of any ancestral work is integration. At your altar, you no longer have to choose between being queer and being spiritual — it becomes a space where every part of you is welcomed and affirmed.

1. Heal Religious Trauma

Building an altar allows Black gay men to form a spiritual connection free from judgment, offering an important pathway for healing from any painful or negative experiences with organised religion.

2. Creates Belonging and Reduces Loneliness

By acting as a physical focal point for spiritual practice, a personal altar can help cultivate mindfulness, create routine, and deepen one’s connection to their cultural or familial history—this can ease feelings of loneliness and isolation.

3. Decolonise Your Identity

Building an altar provides a means of reclaiming Black indigenous perspectives on gender and sexuality and reconnecting with African Traditional Religions, which historically celebrated diverse identities before colonialism.

4. Heightened Awareness and Better Decision-Making:

Consistent altar practice can sharpen your mind, intuition, and inner voice, making it easier to notice subtle signs and cues that offer guidance and boost confidence in decision-making.

5. Build Inner Strength and Growth:

Altar worship strengthens your commitment to personal growth and values, helping you build the resilience and confidence needed to live in alignment with your true self.

Ancestor Worship and Gay Men: Common Fears, Debunked

1. “Will the ancestors reject me for being gay?”

No. There is no evidence in deep African cosmology to support this. Rejection narratives stem from colonial frameworks. In Yoruba philosophy, what matters is Iwa Pele (good character). In Igbo philosophy, it is eziokwu (truth). A gay descendant living ethically is more valued than a straight descendant causing harm (Matory, 2005)[6].

2. “Do I need expensive tools or initiation?”

No. You do not need to buy expensive statues or pay for initiation to speak to your own dead. Water, light, and sincerity are the only requirements to begin.

3. “Am I appropriating?”

For Black people reconnecting with African-derived traditions, this is reclamation, not appropriation. You are picking up the phone to call home.

Conclusion: Begin Where You Are

Building an ancestral altar as a Black gay man is an act of healing, resistance, and self‑recognition. You don’t have to erase any part of yourself to be spiritually whole. Your ancestors endured so you could exist, and they recognise you with that same spirit of survival. Begin simply and speak honestly — this practice can open the door to deeper clarity, grounding, and inner peace.

References

- Abimbola, W. (1997). Ifá will mend our broken world: Thoughts on Yoruba religion and culture in Africa and the diaspora. Aim Books. https://www.thriftbooks.com/w/ifa-will-mend-our-broken-world_wande-abimbola/411718/

- Anderson, J. E. (2005). Conjure in African American society. Louisiana State University Press. Yvonne Patricia Chireau—Swarthmore College Review

- Bae, J. (2022). The Book of Juju. Hay House (Original Publisher). LINK: https://www.bembrooklyn.com/products/the-book-of-juju-africana-spirituality-for-healing-liberation-and-self-discovery-juju-bae

- Hucks, T. E. (2012). Yoruba Traditions and African American Religious Nationalism. UNM Press. https://www.unmpress.com/9780826350763/yoruba-traditions-and-african-american-religious-nationalism/

- Karade, B. I. (1994). The Handbook of Yoruba Religious Concepts. Weiser Books. https://redwheelweiser.com/book/the-handbook-of-yoruba-religious-concepts-9781578636679/?

- Matory, J. L. (2005). Sex and the Empire That Is No More: Gender and the Politics of Metaphor in Oyo Yoruba Religion | Cultural Anthropology. Duke.edu. https://culturalanthropology.duke.edu/books/sex-and-empire-no-more-gender-and-politics-metaphor-oyo-yoruba-religion