By Daniel Nkado.

“DL” stands for “down-low,” a term describing men—often Black or Latino men—who publicly present as straight but privately engage in same-sex relationships.

Originating as an African-American slang for secrecy in the late 1990s, the term later became tied to cultural stigma, media hype, and discreet hookups on apps like Grindr. (Brock, 2020)1.

The term “DL” began as a survival strategy for Black men facing racism, homophobia, and rigid social norms. Today, it’s commonly used as shorthand for “discreet” or “closeted” in gay dating scenes—a shift that brings challenges like misuse, misrepresentation, and commodification.

This article explains the true origin and cultural meaning of “DL” and how it’s performed on gay apps, who benefits, and the harms that follow:

The Origin and Cultural Relevance of ‘DL’

“Down-low” originally meant keeping something private. By the 1990s, it specifically referred to Black men who lived heterosexual lives outwardly but had same-sex encounters in secret.

It is important to note that “DL” identity emerged in Black American communities in the 1990s, a period marked by widespread stigma, the AIDS crisis, and violence and intense discrimination against gay people—pressures that were often intensified for queer Black men due to cultural and historical factors. For many, discretion was not a preference but a means of survival (Ward, 2008)12.

Compared to today’s America, while many issues remain to be addressed, LGBTQ+ people have far greater visibility and protection, which is miles away from the struggles and social hostilities of the 1990s.

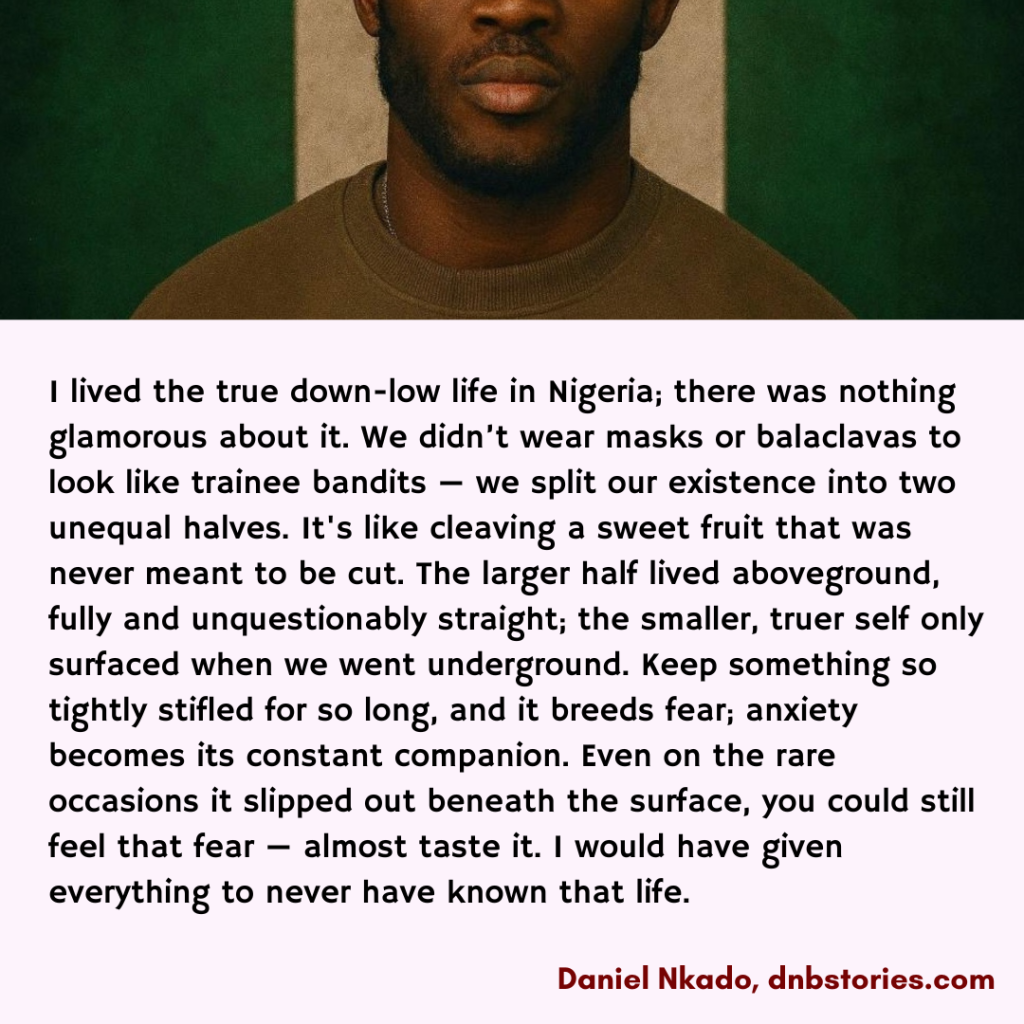

A clear modern parallel can be seen in the experience of gay men in Nigeria today, who live under intense secrecy and fear, navigating harsh laws, social rejection, and the constant threat of violence.

Using “DL” today as a casual tag to boost popularity on gay apps like Grindr, Scruff, or Jack’d—or to project a fetishised, often monetised persona on social media—strips the term of its original cultural meaning and survival context (Brock, 20201; McGlotten, 2013)8.

DL and the HIV Panic of the Early 2000s

In the early 2000s, DL became a media sensation. Headlines in The New York Times and USA Today blamed DL men for rising HIV rates among Black women. J.L. King’s 2004 book On the Down Low depicted them as deceptive, and a 2004 Oprah Winfrey Show episode called it a “hidden epidemic” (King, 2004)6.

Critics called this coverage stigmatising and inaccurate. CDC data from the era later found no direct link between DL men and the rise in HIV among Black women—instead, broader factors like unequal access to healthcare, stigma, and poor sex education were key contributors (CDC, 20072; see also Millett et al., 2005)9.

Monetisation of ‘DL’ Identity on Grindr and Other Apps

On gay dating apps, masculinity (including the promise or performance of it) remains a key driver for visibility and responses, with profiles highlighting traits like “masc,” “rugged,” or “dom” seeing strong engagement.

Research on Grindr3 and similar apps reveals users leverage these identities (“masc,” “dom,” or “DL”) to increase visibility. The use of “DL” in this manner often dilutes the term’s original cultural meaning (Brock, 20201; McGlotten, 2013)8.

DL-Posing on Grindr and Other Apps

Announcing a “DL” identity on hookup apps like Grindr inherently contradicts the very element that defines it—secrecy—it’s like a spy broadcasting their cover story.

For someone truly closeted (e.g., a married gay man living in a homophobic environment like Uganda), using “DL” publicly risks exposure, gossip, or blackmail (McGlotten, 2013)8.

Many profiles on Grindr, Scruff, and Jack’d with loud “DL” signals often belong to the subset of posers and performers: gay or bisexual men without a genuine need for secrecy who adopt the label or aesthetic to enhance desirability or project “high-grade” masculinity. Here, DL shifts from protection to an eroticized brand, highlighting a complex irony: the same stigmas that harm queer people are sometimes repackaged as desirable traits (Han, 2015)4.

Genuine DL vs. DL Posing

| Feature | Genuine DL Man (Context: Survival) | DL Poser (Context: Commodification) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Motivation | Safety and survival amid homophobia; protecting status, career, or family | Self-promotion to boost engagement and desirability |

| Origin of Secrecy | Homophobic environments (cultural, religious, geographic pressures) | Dating market’s fixation on “masc” and taboo aesthetics |

| Goal on Apps | Avoids apps; prefers private messaging and vetting | Ego boost; emphasises masculinity and inaccessibility |

| Pacing | Takes weeks for meet-ups with careful vetting | Instantaneous, minimal or no vetting |

| Emotional Stakes | High (fear of rejection or loss); stressful and isolating | Low; chosen for transactional gain |

| Cultural Context | Historically tied to older Black and Latino men navigating racism and other pressures | Often detached from history, used to project “hot and discreet” |

Using the DL Image to Sell Self

The appeal of the DL identity often lies in the fetishisation of rugged masculinity and inaccessibility in gay dating culture. By adopting a “DL look” or persona, performers position themselves as an “exclusive prize.”

For those seeking DL‑labelled partners, the pursuit can offer a temporary ego boost and a sense of status that openly gay connections may not provide, turning the interaction into a transactional exchange that ignores the label’s original cultural and historical significance. (Brock, 2020)1.

Using the DL Identity to Create Superiority

In relatively safe locations—such as major U.S. cities, Canada, and the UK—the ongoing use of the DL label or performance of the DL persona (e.g., masking at hookups, deleting social profiles, frequently changing phone numbers) often isn’t driven by any real need for discretion but instead to signal exclusivity.

This leads to perceived hierarchies within queer spaces, where individuals leverage the label to differentiate themselves, even while their behaviour aligns with openly gay norms (e.g., using Grindr, queer slang, or socialising in gay circles).

‘Playing the DL Card’ on Grindr, Jack’d, and Other Apps

“Playing the DL card” refers to using the label performatively on gay apps for personal branding, separate from survival needs. Users often do this to attract those drawn to “straight-passing” archetypes.

Common tactics include:

- Inventing a “DL Look”: Masculine markers like “masc only, no fems” or stereotypical outfits (e.g., tracksuits, balaclavas) to appeal visually.

- Negotiating Availability: Setting limits (“strictly DL”) to avoid commitment or assert control.

- Evading Identity: Claiming distance from the “gay scene” as a point of distinction.

- Self-Marketing: Using DL for visibility in low-risk areas.

- Segregation Tool: Employing the persona to define hierarchies and monopolise the meaning of being “out” and “not”, an approach viewed as exploitative.

The DL persona often projects the “straight-passing mystique,” expressed through behaviours like appearing publicly only with women or straight friends, engaging in straight-coded hobbies, or adopting mannerisms that blend seamlessly into heteronormative spaces—traits that many gay men find alluring and sexually desirable.

Is DL losing relevance in gay dating culture?

While the “DL” (down‑low) tag and other “discreet” labels remain common on apps like Grindr, their appeal feels like it’s waning in some queer circles, especially among Gen Zs. Platform data still shows strong use of discreet and DL‑adjacent tags and steady engagement, but some users report growing fatigue with the hype.

Social chatter from 2024–25 — viral X, Reddit and TikTok threads, commentaries, and community debates — frames DL behaviour more often as risky, flaky, or performative than desirable, especially in progressive cities. As norms around gay intimacy and sexual roles shift, a growing number of former posers may be embracing authenticity (Moss, 2006)11.

In more conservative regions, however, DL practices still function as real safety strategies. As we await harder metrics and targeted surveys, this might be more of a localised vibe shift than a verified broader downturn.

Final Word:

Ultimately, when DL is performed for gain rather than necessity, it risks diluting its meaning and harming queer communities—prompting calls for more authentic self-representation (Han, 20155; McGlotten, 2013)8.

References

- Brock, A. L., Jr. (2020). Distributed Blackness: African American cybercultures. NYU Press. https://opensquare.nyupress.org/books/9781479811908/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS — 33 states, 2001–2005. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 56(9), 189–193. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5609a1.htm

- Grindr. (2024). Grindr Unwrapped 2024. https://www.grindr.com/unwrapped

- Han, C. (2007). They don’t want to cruise your type: Gay men of colour and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630601163379

- Han, C. S. (2015). Geisha of a different kind: Race and sexuality in Gaysian America. NYU Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/719601/geisha-of-a-different-kind-race-and-sexuality-in-gaysian-america-pdf

- King, J. L. (2004). On the down low: A journey into the lives of “straight” Black men who sleep with men. Broadway Books. https://books.google.com/books/about/On_the_Down_Low.html?id=Cvowv8XqKCwC

- McCune, J. Q. (2014). Sexual discretion: Black masculinity and the politics of passing. University of Chicago Press.

- McGlotten, S. (2013). Virtual intimacies: Media, affect, and queer sociality. SUNY Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/2674153/virtual-intimacies-media-affect-and-queer-sociality-pdf

- Millett, G., Malebranche, D., Mason, B., & Spikes, P. (2005). Focusing “down low”: bisexual black men, HIV risk and heterosexual transmission. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7 Suppl), 52S. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2640641/

- Mowlabocus, S. (2016). Gaydar culture: Gay men, technology and embodiment in the digital age. Routledge.

- Moss, D. (2006). Masculinity as Masquerade. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 54(4), 1187–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651060540041301

- Ward, J. (2008). Respectably queer: Diversity culture in LGBT activist organisations. Vanderbilt University Press. https://escholarship.org/content/qt3n77w95w/qt3n77w95w_noSplash_4dd646bb05267b25ce2b0a59eceb85fe.pdf