When an African prince and a white middle-class clerk from Lloyd’s underwriters got married in 1948, it provoked shock both in Britain and Africa.

Their romance caused major political and diplomatic ructions.

But the extraordinary love story of the late Botswanan president Sir Seretse Khama and his middle-class English wife Ruth Williams endured despite all the obstacles and outrage.

So powerful was the tale that it has been made into a movie.

The 2016 biographical romantic drama A United Kingdom is based on the true-life romance between Sir Seretse Khama and his wife Ruth Williams Khama.

|

| David Oyelowo and Rosamund Pike portray Seretse and Ruth, respectively. |

At the time, the relationship between late Botswanan president Sir Seretse Khama and his middle-class white English wife Ruth Williams became the focus of a crisis between Britain and Botswana’s neighbour South Africa. South Africa was just about to introduce apartheid.

Seretse, the Oxford-educated student prince from the British protectorate of what was then Bechuanaland in 1948, at 27, married Ruth – a 24-year-old clerk with a Lloyd’s underwriter.

Their union was fiercely opposed by her father and Seretse’s family.

He was chief in waiting of the Bamangwato tribe and had been sent to London by his uncle Tshekedi Khama to study law, after which he was to return home and marry a woman from his tribe.

The British government and the uncle ended up joining forces to demand that Seretse give up his white wife, or quit his tribal lands and leave his homeland.

As Amma Asante, director of A United Kingdom, said: ‘They were sent into exile because of their forbidden love.’

|

| Seretse Khama with his English wife Ruth, and their two children Jacqueline and Seretse Jr in September 1956 |

Ruth Williams was born in Blackheath, South-East London, the daughter of a former Indian Army captain who later worked in the tea trade.

She loved jazz; so did Seretse. They met when Ruth’s sister Muriel took her to a London Missionary Society dance in 1947 where Seretse asked her to dance.

At that time in post-war Britain, only 0.02 percent of the people were black. Prejudice was fervent and interracial couples were largely nonexistent.

It was a whirlwind romance.

Seretse didn’t seek consent from his uncle because he knew it would be denied, but Ruth had to ask her father George, who argued that she should not marry a black man.

But she ignored him.

Actress Rosamund Pike told the Daily Mail: ‘Ruth’s fear was telling her father, because she knew it was going to be a hurdle.

‘But I don’t think she thought for a million years that they were suddenly going to have the weight of the British government coming down on them, or that a high-up politician would come into her office saying, “If you go ahead with this, you’re going to bring down the British empire in Africa”.

It sounds absurd, but that’s what he said.’

|

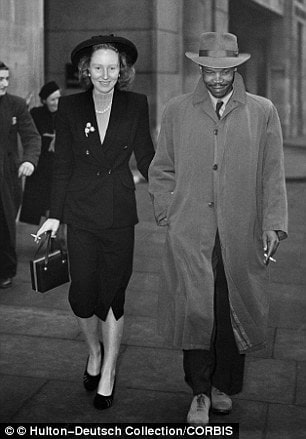

| The first picture of Ruth and Seretse Khama after the news of their marriage was released in 1948 |

Apartheid was about to be enshrined in South Africa, and Britain was reluctant to damage relations with that country.

‘South Africa made strong representations to the British government that if they were seen to condone the marriage of a white woman to an African, there would be a commonwealth and constitutional crisis,’ said Pike.

While this was going on, Seretse’s uncle Chief Tshekedi also insisted that the Colonial Office prevent the marriage.

A parson who was meant to marry the pair was told in no certain terms he should not officiate at the wedding.

William Wand, the Bishop of London, would only give his blessing if the government supported the nuptials, which they of course did not.

The bishop actually telephoned the priest the morning of the marriage to tell him not to perform the wedding.

As a result, the couple decided to have a civil ceremony a few days later, tying the knot on September 29, 1948 at Kensington Register Office.

After they were married, they lived in a small London flat for a time.

The following year they returned to his tribe in Bechuanaland, thinking their problems were over.

But Tshekedi was enraged and summoned tribal elders to a meeting, at which blood relatives of Seretse opposed the marriage.

They said Ruth would not be recognised as tribal queen. But Seretse and his supporters realised that Tshekedi wanted to be king himself. Though many felt he was simply a conservative, locked in the ‘old ways’.

There were three tribal meetings to discuss the crisis over a period of seven months. At the final meeting there were 9,000 present and only 40 objected to Seretse becoming king and his wife queen.

|

| Sir Seretse Khama, President of Botswwana and Lady Khama (second right), pose with the Queen and Princess Anne at Buckingham Palace, where the President and his wife lunched with the Queen |

Meanwhile, furious telegrams were being sent between the UK and South African governments, with Pretoria insisting the marriage breached race laws.

|

| The couple pictured on January 6, 1949 in London |

The South African prime minister denounced the union as ‘nauseating’.

With his young wife now pregnant, Seretse was invited back to London to meet Commonwealth Office ministers while Ruth remained in Bechaunaland. It was a trap.

British officials insisted he give up all claims to the chieftainship.

When he refused, he was told he would be banished from his homeland for five years.

There was an outcry and political supporters formed a committee to take up Seretse’s cause.

In 1956, leaders of the Bamangwato tribe sent a telegram to the Queen to ask for their chief to be allowed to return home.

When he did, finally, go back, Seretse gave up all rights to the throne. Instead, he held the country’s first democratic elections and was voted president of what became Botswana.

The couple had a daughter and three sons, one of whom, Ian, is now president of Botswana.

Seretse died in his wife’s arms aged 59 in 1980.

Ruth died aged 78 in 2002.

The biographical film has all the attributes of a good motion picture – major actors, important director, explosive and compelling story – that will attract audiences and, just as importantly, as many thought, Oscar voters.

|

| A United Kingdom movie poster |

For Oyelowo, many believed it was a role that could land him the coveted Oscar nomination, an honour denied him two years before when he starred as Martin Luther King in the film Selma.

But Oyelowo who said he was attracted by the ‘epic nature of the love story, and the backdrop of the British empire, and what it was like to be a king in Africa just as apartheid was being signed into law in South Africa’ was again caught up in the Oscar’s common practice of ignoring diversity.

Wow…wonder why movies like this doesn't get popular.

I love this story!

Wow..

Just watched it. its awesome!