by Daniel Nkado

Grandpa is tall and lean.

Even with the so many wrinkles on his face you can always still tell he is Daddy’s father. Somehow.

Their smiles are the same, even their eyes. That shiny darkness of mbembe fruit.

Sometimes I wonder if Daddy knew this, if he ever realized how much he looked like Grandpa. I thought that if he did, that, maybe, he wouldn’t refer to him as ‘that old man’ and allow us go visit him sometimes.

‘Can you imagine that old man has set up a village war against me?’ Daddy was saying to Mummy one evening. ‘Can you imagine that?’

‘Why not just go and see him and apologize?’ Mummy suggested, her voice low in the characteristic manner he suggested things to Daddy.

‘Why?’ Daddy asked.

Mummy gave a tiny shrug and said nothing. Daddy’s voice was loud and she knew better.

‘Why would you say that?’ Daddy asked again. ‘What did I do to him that I should be apologizing for? Tell me.’

Mummy never said a word again.

Daddy had been upset with Grandpa since I was born, or since I knew I was born. That had been over thirteen years ago. Till now I haven’t understood the full story. All I had been able to gather— from spontaneous Grandpa discussions that ended quite the same way they started— was that Grandpa had chosen Uncle Peter, Daddy’s younger brother, over Daddy.

Uncle Peter resides in America. Daddy doesn’t say much about him, but at least I never heard him call him names.

There was one evening Ndubuisi, our house boy, came into the sitting room and told Daddy that his father was at the gate. Daddy’s face swung to him in surprise.

I was expecting to hear, ‘Oh please let him in’, or something even more welcoming, but what Daddy said was, ‘What is that old man doing here? Who even gave him this address?’

He stood and followed Ndu to the gate. I followed them quietly—I was sure Daddy would have asked me to go back if he’d seen me.

Ndubuisi opened the gate and I hid behind the other half, peeping.

That was the first time I ever saw Grandpa. He was tall like Daddy. His long black cap even made him appear taller. He wore a long brown Ankara shirt over matching trousers. His feet were long and a toe or two poked out from his sandals which had gone threadbare from age.

His toe nails were long and dirty. Had Daddy allowed him inside, the first thing I would have done would be to cut his toe nails.

But Daddy didn’t allow him inside. ‘What are you doing here?’ Daddy’s voice was least welcoming.

‘Ezekiel, I must talk to you,’ Grandpa said. ‘The cassava tree does not grow past its cultivator.’ Grandpa spoke Igbo differently. His words flowed with excellent rhythm, like rehearsed speech.

The few times Daddy spoke Igbo was with that frequent pauses that meant this was a language he was growing out of. So his Igbo was always mingled with English.

Daddy thrust his hand into his pocket and brought out a bundle of Naira notes. He counted a few notes from it and put the rest back into his pocket. He gave Ndubuisi the money. ‘Find a taxi to take him back to the village.’

Daddy turned and caught me peeping. ‘Juliet, what are you doing there? Run inside at once!’

Grandpa’s voice was loud behind the locked gate. ‘Ezekiel! Ezekiel! Ezekiel, allow me set eyes on my grandchild, Ezekiel! What wrong did I commit for not allowing you to kill your only brother?’

‘Are the two of you not all that I have?’ — Grandpa’s voice suddenly dipped. I wondered if he was about to cry.

I wanted to go out then and tell Grandpa to not say all these things. That they would only make Daddy angry with him the more, that it limited the chance of Daddy ever forgiving him. For whatever sin he committed that was so unforgivable.

I had been very excited when Daddy said we’d be travelling to the village this Christmas. Finally I was going to see Grandpa. I thought maybe Daddy has finally forgiven him.

But after two days in the village and I have not seen Grandpa, my excitement took a plunge.

Grandpa’s house was not very far from our village house, Mum told me this. She said that we had in fact passed it as we drove to our house.

I was annoyed with Mummy for not pointing at Grandpa’s house for me.

But Grandpa came to the house yesterday. Daddy was away. It was Ndubuisi again that came to tell us. This time he’d passed the information in lowered voice, ‘Papa is around’, as if it was one heavy gossip.

Mummy and I were rushing to steal a meeting with Grandpa when the small gate swung open, stilling us halfway. It wasn’t Grandpa that came in. It was Daddy. He came through and bolted the gate.

We walked back into the house, disappointed.

Inside, Daddy warned Ndubuisi ‘not to ever dare to’ open his gate for that old man.

‘A trykwana mepee my gate for that old man ubochi ozo, inulia?’

But something remarkable happened this morning when we were visited by Papa Christmas.

We have just come back from church when we heard ringing sounds at the gate.

Daddy had hissed and asked Ndubuisi to go and send those masquerades away.

Ndubuisi returned shortly to tell Daddy that it wasn’t a masquerade. That it was Father Christmas.

Daddy gave Mummy a look that said it was both surprising and amusing. A Father Christmas in the village.

Daddy and Mummy started toward the gate and I followed them. I knew Daddy would not send me back. It was a Santa’s visit, after all.

When Daddy opened the gate, the Santa I saw looked funny. Very funny.

He had no Santa body, no white beard, no white-collar red coat or hat. Tall and lean, he wore a long gown, a green gown that looked like something I’ve seen on Mummy before.

His limp stripped hat –the kind titled Igbo men wore to village meetings— fell back from his head. Dark gloves covered his hands. His face was painted dirtily with white chalk and his black beard was made with an old lady’s wig.

I stared at this tall and lean Santa, resisting the urge to laugh.

‘What are you?’ Daddy asked him.

He jiggled his bell again, sending a burst of ringing noise into the air. He pulled the bag slung across his shoulder to his front and brought out a red balloon. He put it back and brought out a blue one. However he got to know blue is my favorite color I can’t tell.

He extended the balloon to me. ‘Papa Christmas brought gifts,’ he said, his face lit up in a great toothy smile.

I looked at Daddy.

‘Allow her,’ Mummy said.

Daddy nodded.

I got close and took the balloon from him. It was then that I saw his sandal and remembered it. His nails had become even longer, and dirtier.

‘Go and bring money so that we give him,’ I heard Mummy tell Daddy.

As soon as Daddy left the gate, Mummy came close to us. ‘Her name is Juliet,’ Mummy said in Igbo.

I looked at her, surprised.

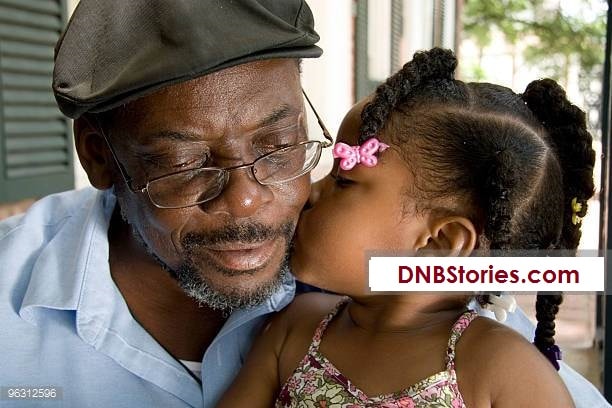

Papa Christmas put his two hands on his chest and said, ‘Awuu! Nwam!’ He hugged me tight. He smelled of the inexplicable scent of old people. Something fusty yet fresh.

‘Grandpa,’ I called him.

‘Nwa m—my child.’ He hugged me again.

‘Okay. Enough Santa time.’ It was Daddy’s voice.

Grandpa and I quickly disengaged.

Mummy collected the money from Daddy and gave Grandpa. He was nodding rhythmically as he took the money, as if to a silent song — obviously characteristic of African Santas.

He waved at us with both hands and walked away.

It was the best Christmas ever.

***

Get all complete stories by Daniel Nkado on DNB Store, OkadaBooks or Flip Library!

Awww

Touching.

Her father is surely a terrible fellow.

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful post. Thanks for providing these details.

Thank you