THREE

They brought wine today.

It was meant to be a small occasion, smaller than a normal wine-carrying ceremony. They had come with just two elders; one was Ichie Okwu, an elderly kin and the other Amaechi, Obinna’s uncle.

Ichie Okwu was tall and thin. He walked with a stoop, while Amaechi, short and round in his big polo shirt and broad brown trousers, bounced beside him.

Behind them, Obinna, his mother, his younger brother, Uzochukwu, and Ogechi, Amaechi’s wife, strolled along.

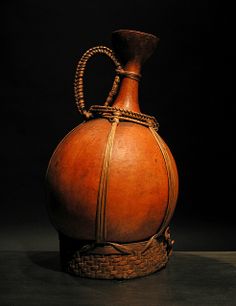

He was carrying the wine— a round gourd with fresh palm leaves stuffed to the mouth. It was said that the leaves would stop the wine from frothing over, but it still frothed anyway.

Bees buzzed around the mouth and once in a while Obinna waved around to drive them off.

‘Faga agba gi—they will sting you,’ his mother said.

He smiled and continued to drive the bees.

He looked at his mother and smiled again, differently now— shyly.

His mother smiled back at him with her lips turned down. ‘Ndi di agaba— husbands are moving,’ she murmured.

Her eyes met with Ogechi’s, and she began to chuckle. She leaned to Mama Obinna’s ear. ‘He should not forget to leave her with child before travelling,’ she whispered.

Mama Obinna laughed—a short he-he-he laugh that made it difficult to tell if she was truly amused at what the tall woman had said or just found it ridiculous.

Obinna heard them and turned away with a smile.

The smile lingered on his face. He was happy.

When his mother had suggested they carry wine to Ada’s parents and pay her bride price before his travel—to secure her fully— he’d felt awkward.

‘She will wait for me, Mama,’ he’d said to his mother. ‘She will, I know.’

Mama Obinna had hissed and told her son he knew nothing.

But now that they were on their way to their in-law’s house, he was happy. An exciting feeling of security swamped over him.

To be tied to her in marriage, the perfect assurance that she’d wait.

That she must.

‘Brother?’ his little brother called. ‘Don’t you think I should have carried my own wine too?’

They turned to look at the boy.

‘Uzochukwu, why do you think you should have carried wine too?’ their mother asked.

‘So that we pay Ugochi’s bride price too.’

Obinna was smiling. ‘You want to marry Ada’s sister?’

‘Not really,’ the boy said. ‘I don’t really like her. She talks too much, but she is the only one I can marry. I asked Ada’s friend, Ujunwa, to marry me and she laughed at me and said that I am still a small boy.’

Ogechi burst into laughter.

Mama Obinna was smiling and shaking her head.

Obinna placed one hand on his little brother’s shoulder. ‘Nnam, don’t worry, when the time comes, you will find a very good girl to marry, inu?’

‘That will be as beautiful as Adaku?’ the boy asked.

Obinna nodded. ‘Even more beautiful.’ He nestled the boy to his side.

***

Onochie and his wife, Uchechi, received their visitors well.

Three long benches were set under the orange tree in the front of their compound.

Four elders came from their side, two with their wives. The women all dressed well, in expensive or expensive-looking wrappers, blouses and matching stiff-fabric scarves.

Clothes that smelt heavily of camphor, indicating how very sparingly they were worn.

Ichie Okwu and Amaechi joined the other elders on the bench. They had all greeted in the way titled men do, slamming the back of their palms together, three times before taking each other’s hand.

The ones with animal skin fans used them.

Mama Obinna and Amaechi’s wife joined Uchechi in the backyard.

The jollof rice was done, hot, spicy and reddish. Uchechi was transferring it into a fat yellow cooler with a stainless steel plate. Another woman beside her was washing cups and plates and another rinsing them.

Mama Ukaa, the lanky woman well famed throughout the entire Iruowelle for her perfect ogiri, was at the fire place, quenching the cinders with water. She would sprinkle some water and the fire would give out a squeal as if in pain, raising a dust of ashes.

Uchechi stood and hugged Obinna’s mother. ‘Nwanne ayoola ogo—a sister has turned an in-law!’ she said, and they laughed.

‘Is the rice not too much?’ Mama Obinna asked.

Uchechi hummed. ‘Just wait till they start coming.’ She sat down to her work again.

Mama Obinna pulled a nearby back chair and sat beside her.

‘If not for the short notice, I’d have prepared ugba. You know na, ugba eji mala nwa Akwaeze [ugba with which they know a daughter of Akwaeze]!’

‘Awuu!’ Mama Obinna inclined her head. ‘Ada mmadu!’ They slapped their palms together.

She looked round. ‘My wife nko?’

Uchechi hummed. ‘That one? She has been in her room all morning with her friends.’ She joined her thumb and index finger together in the air. ‘Ordinary pepper she would not help me grind.’

Mama Obinna was laughing.

Uchechi dropped an open palm on her lap. ‘Hope your son is aware she doesn’t know how to cook?’

The women burst into laughter.

‘That one is no problem, my sister,’ Mama Obinna said. ‘I will gladly teach her.’

Uchechi gave a small, slow nod, as if in pity. ‘Ngwanu, God will be your strength. Even the goats and chickens know that I’ve tried!’

Another bout of laughter.

***

At the front of the house, Papa Adaku brought out a tray of kola and dropped it on the table in front of the men. ‘My brothers, kola has come,’ he said.

In the tray, were five large kola nut seeds beside a mound of garden egg fruits. Ugochi, Adaku’s younger sister, came out with a flat plate, a jar of groundnut butter and spoon. She dropped the items on the table beside the tray.

‘The king’s kola is in his hands,’ an elderly chief said.

The others nodded in support, muttering.

Adaku’s father picked one kola seed from the tray and gave the elderly chief, saying a proverb about the king respecting the presence of an elder too.

The elderly man took the kola from him, leaned forward and cleared his throat. He began to say the prayers and the others chorused ‘Ise!’ at the end of every line.

When he was done, he broke the kola and threw the pieces inside the plate. ‘Ha!’ he exclaimed. ‘Oji udo—the kola of peace! Nwanne ayana nwanne ya—a brother should not move without the brother!’

They nodded and called him his title. ‘Eziokwu-bu-ndu!’

Soon, the women came to join them.

From the louvered window, Ada and her friends peeped at Obinna. He stood now with his best friends, Obiozo, Uche and Ahanna.

He was talking and Ada wondered what he was saying, if it was about her. She was surprised to realize he was different today; he looked different.

She saw him differently. The fact that he was going to become her husband that day created an aura of respect, esteem.

‘You are marrying the best, Ada,’ Nwamaka said, in that tone of voice that showed she was both happy for her and jealous.

Ada turned to look at her. ‘But he doesn’t have money,’ she said, yet not appearing to be sad.

‘Did you say money?’ Ujunwa threw in. ‘Who is talking about money these days again? Haven’t our girls all tried it and saw it led nowhere? Happiness is the main thing, my friend. Obinna will make you happy.’

Nwamaka nodded fully, indicating her full support.

She understood, perfectly, for she had been a victim of ‘money marriage’ herself.

Azuka who had been sitting on the bed all the while they peeped got up. ‘I’m yet to understand how people can be truly happy in marriage without money though,’ she said.

They turned suddenly to her.

She looked unapologetic. ‘Yes,’ she affirmed. ‘You see, marriage is an expensive institution, like a company with workers, it needs money to grow. When there is no money, the workers can only stay a few weeks, months highest, before they revolt.’

They were staring at her.

‘I don’t believe you, Azuka!’ Ujunwa was first to speak. She wanted to continue in the same quick pace, but paused.

It was Azuka that has spoken; she needed to give a very reasonable reply to silence her completely, and also to stop Ada from thinking about it.

But Adaku was not any bothered. Not when it was about marrying Obinna. She had never been surer of anything her entire life.

She gave Azuka a small smile. ‘I think, Azu, that when the owners of the company are bonded enough, they will always work something out.’

Her eyes lingered on Azuka, her lips still slightly curved in the smile.

Azuka flattened her cheeks and did not say another word.

Soon, her mother knocked and said it was time for her to come out. She turned to her friends and they giggled with excitement. Except Azuka.

The trio hugged themselves before stepping out.

She was amazed at the crowd that had come. They had hoped it to be a small occasion, but then, it was an eating and drinking occasion.

There is a popular saying in Obeledu that you don’t know how many friends you have till you call a party.

She stood in the middle, hands folded in the front. Her friends stood behind her, smiling and shy.

One of the elders, Ichie Akunne, who was her father’s eldest brother, stood and called her. ‘Omalicha, come.’

She walked close to him and knelt.

Ichie Akunne poured out a glass of wine and gave to her. ‘Stand, my daughter. Go and show us your husband!’

‘Yes, nna anyi!’

‘And if he is not here, come back let us go to Nkwo and buy you a man,’ another elder said beside them, cackling.

Adaku stood and looked round.

He was easy to find. He smiled at her and her fingers around the cup quivered a little.

She started to move, one graceful step after another.

‘Omalicha!’

‘Asa mma!’

‘Elelebe eje oru!’

They were calling her, extending their hands in false desire.

Finally, she knelt before him, drank a little from the cup and handed it to him.

The crowd cheered.

FOUR

He came early to her house.

His trip was the next day. He’d promised to spend the entire day with her today.

As if that would change anything. But she had agreed anyway.

They went two trips to the borehole together. And then he helped her split wood.

He took the axe and she stood behind him, watching.

Each time he lifted the axe, his arms firm in the air as they clasped the tool, his left foot holding the wood secure to the ground, she thought about how much she was going to miss him, those arms, those thighs, his chest, his lips.

His touch.

And now he turned to her and smiled; that smile too—she quickly added that one. She bit her thumbnail off and hugged herself.

Her mother came out and smiled at the huge pile of firewood.

It was enough to last them a month. She thanked him and gave him a lump of dried meat from her stock.

He was putting it in his mouth when Ada jerked it off and ate it instead.

She was laughing as his face crumpled like he was going to cry.

‘Nnaa, don’t mind her,’ Uchechi told him. ‘There is another.’ She gave him another larger lump of meat.

He put it quickly into his mouth and flashed his tongue at Ada.

Ada stopped laughing.

Obinna started to laugh and she picked a stick from the ground and pursued him.

Uchechi was smiling and shaking her head.

Her family accepted him, and it wasn’t just because he frequently came around to help them with the firewood, or water or cut down their ripe palm fruits.

Or because he never collects money each time he carried Uchechi’s wares at the market, even when she insisted, aggressively so, sometimes forcing the note into this hand, he would still return it.

It was because he was hard working. And his family, though poor, was good.

Papa Adaku had once said to the wife, when the trouble of getting their daughter to see reason why she shouldn’t wait for someone so young for marriage seemed to overpower them, that in any case they should be happy at least that it was him, that ‘at least’ they are sure their daughter won’t die of hunger.

***

After she made jollof rice with the dry fish her mother brought out, they sat together under the shade of the mango tree at the other end of the backyard to eat.

He took a spoonful of the yellow rice, blew at it once and threw it into his mouth. ‘Aw!’ he screamed.’

‘What?!’

‘Oku!’

She frowned at him. She used her spoon and levelled the rice so that it cooled faster.

He picked a lump of fish from the plate and threw into his mouth.

She slapped his arm. ‘Mind yourself, Obinna.’

He liked the way she had called Obinna— quietly, affectionately, the failed attempt of someone who was only pretending to be angry.

There was silence for a while. Now his eyes were on her. She met his gaze and they held briefly, then she turned away. ‘So will you write me?’ she asked him.

‘No,’ he said.

Her eyes came wider. ‘You won’t? Why?’

‘I’m going to be very busy,’ he said.

‘Busy?’

‘Yes!’

‘With what?!’

‘Ha! You’ve not heard? Ahanna said the girls in Lagos never get satisfied. Like dogs, they keep asking for more, more, more and more!’

He looked and saw her expression. He felt amused but did not show it.

‘Ayi!’ He screamed when a glass of cold water splashed over his face.

She dropped the glass back on the table with force and carried the plate of food to herself.

‘Ada! Why did you pour water on me?’

She didn’t say a word, instead she began humming in the way little children do when they want to show they are eating something tasty.

He stared at her. He picked his spoon and tried to eat from the plate. She shifted. ‘Ok, now I can’t even eat?’

More humming. ‘Allow me to eat! Maybe you have not heard, the men in the university never get satisfied too. I must eat before they kill me.’

He was staring at her.

Such jokes got to him easier, she knew.

‘Oya, ndo—sorry!’ he said.

She nodded. ‘Better.’ She dropped the plate back on the table.

‘I will write you every week, inu?’ he said, his voice distorted by chewing.

She laughed instead, a dry ‘he-he-he’ chuckle that surprised him. ‘Who will even have time to read your letters when I will be busy with my studies in the university?’ she said.

Now he laughed, so loudly she stopped to stare at him. ‘What’s so funny?’ she asked.

He wanted to say something and then started on another bout of laughter.

‘Mkpi!’ she called him, her face swollen in a frown.

‘What do you know about the university?’ he came through at last. ‘Eh, Adaku Onochie, answer me?’

She rolled her eyes at him. ‘What do you mean by that?’

‘Do you know how many times you will even write JAMB before you finally get admission, eh? You think you just write one JAMB and fiam, you get admission, just like that. Look, let me tell you, you have to write JAMB at least four times—’ He put up four fingers in demonstration. ‘Ano! Four times, before you can even talk about getting admission.’

She turned her hand round her head and snapped at him. ‘If it is charm, it will not work for you!’

He laughed. ‘But, Ada, seriously, were you hoping you just write JAMB today and tomorrow you are a university student?’

‘Once I pass, I will get admission,’ she said.

‘Taa! Pass fire! Better go and ask Ukamaka your friend. She has written that JAMB more than five times and yet she is still here with us. I heard she now has her own special locker in the exam hall with her name on it. I’m sure this year, they will register her for free.’

She didn’t want to, but she laughed. Then she turned serious. ‘Am I as dumb as Ukamaka, gbo?’

He didn’t respond.

He was now staring at her.

At that moment it hit him what he was going to miss.

The love.

The friendship.

The laughter.

Tiny sands of fear settled on him.

He began to wonder if his trip would tell badly on their relationship. If it would spoil this wonderful union.

He thought of her in the university, a large compound filled with young boys; disco boys in their saggy jean trousers, broad T-shirts and bandanna, each trying to grab her as she sashayed through their middle, desperate to defile her.

To take away her glow and leave nothing for him.

Her voice jolted him back to life. ‘Obinna!’

He turned suddenly to her, looking lost.

‘What are you thinking about?’ she asked him.

‘Nothing.’ He said nothing quietly.

‘Don’t worry, I will wait,’ she said.

‘Mm, what did you say?’

‘I said I will wait for you.’

He was amazed she understood. No one knew him like she does.

‘I don’t trust university boys,’ he said.

‘I don’t trust Lagos girls either.’

‘Ha, you know I can’t do that.’

‘What if they keep asking for more, and more and more?’

He smiled and his dimples sank deep into his cheeks.

Later that evening, they went to the avocado tree and felt each other. It was intense, the deepest they’ve ever had, as though doing it that way would keep them satisfied till whenever they would meet again.

'Avocado tree and felt each other', As a confirmed in-law, what happens to his room?

There is something about doing it in the bush, Iyke.

#NotTalkingOutOfExperience o

Her hair will be sandy and dry leaves will stuck on her wrapper !chai, you don spoil finish!

How do you know her hair will be sandy and that leaves will be stuck to her wrapper, Iyke?

Have you gone to the bush to fetch firewood before too?

Wow! again. I understand her plight. Hope their love stands the test of time

Sweet village love. I wish they last oo

Dan you asked if he's gone to the bush to fetch firewood too meaning you've been there before lol bad boys

No. No. No. I was just talking about firewood o! Fire + Wood food is done!

Love at its best!

Thus kind love

it can b loving and also painful.

I pray d love is as strong as iroko tree.

Interesting………….

Hmmmmmm, someone z testifying to the switnes of bush Xperince

I wonder o

Dan I think ds d second tym u re saying sumtyn abt avocado tree tin….hmmmm….thnk I ll strt watchn out each tym I pas one of doz trees

as for Obinna, u betr no fal hand, I trust ada sha

Abi o

Pls tell me

Hahahah…the earliest men had it in bushes and caves. The feel of nature caps the activity. The openness, the fresh air, the boundless sky, singing birds…hurricane orgasm!

This is my personal view and does not represent the opinion of DNB Stories.

LOLs. The tree is wonderful. Cool shade and very safe [Avocado fruit can't kill.]

Don't go near the breadfruit tree o or coconut or Peter mango.

Woah dis story remind me sumtin.

Nice 1 Dan

Hmm. tell us d story ma

Lol

Nice story

Lol

Sorry Vick is not 4 ur hearing o

Daniel will b a warrior on bed….

I'm in interesed too o

Nice and interesting? story