Chapter One

Ada is your sister, Mama Obinna said this to her son often.

‘Take this to your sister,’ she said, handing Obinna the black polyethylene bag that contained Ada’s dress, the one she’d helped her mend. ‘Tell Uchechi my sister that I’ll now see her at the market tomorrow.’

The thing is, Mama Obinna called everyone close to her either brother or sister. It’s usually that way—their real names at first then they become too familiar and she quickly adopts them.

Probably that was why her son, Obinna, never believed Ada was his sister.

When they were little, anytime Ada came around—and it was often that she did—Mama Obinna would give them okpa in one plate.

Then, little Obinna in the influence of that rebellious attitude of growing boys, would grumble in protest.

‘Mechie onu osiso!’ Mama Obinna would snap at her son. ‘Shut up and eat with your sister!’

When Obinna reluctantly dropped back to the floor to join her, Ada would smile at him – as though she had only been entertained by the little boy’s folly— before swallowing her food.

In the smile, she looked like an adult bottled up inside an infant’s body.

Obinna has come to understand that smile now—that feeble bending of her lips with her eyes narrowed, a calculated representation of unknowingness on the outside, yet abundance of knowledge in the inside.

He’d come to understand now, too, many other things she usually did that was not very easy to discern. Hers has always been that of complex expressions.

She was never the easy kind to read, so the feeling of being the only one quite able to, at least, always left him glad.

***

‘Ada,’ Ujunwa murmured beside Ada again. ‘Ada, it’s him.’

Again, Adaku pretended not to have heard anything, not Ujunwa’s whispering, not Obinna’s beckoning whistle.

She ran a finger across her wet forehead to stop the water from her metal bucket from trickling into her eyes.

It was the drier months of the year and the road to the borehole now seemed wider, with the lush vegetation that used to fringe it all gone.

‘Ada, chelu! I was calling you.’ He was with them now.

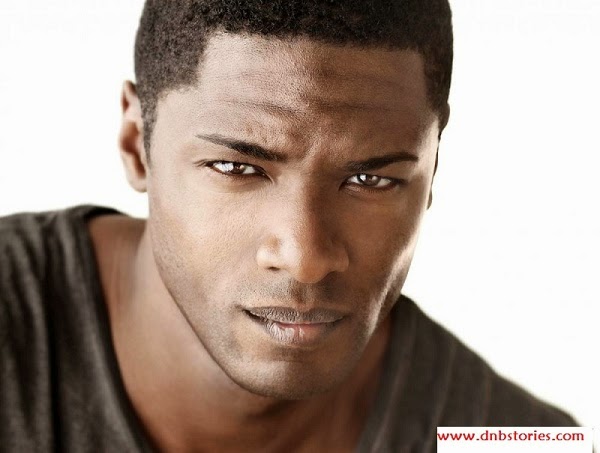

Running was easy for him. Even so, he walked with so much confidence one could easily assume him a prince, which he was not.

He had slight bowlegs, and Ada had once told her friends; Ujunwa and Ogechi, that that was what gave him his quick gait, like the bowlegs of nwamkpi, her mother’s sprightly odd-legged he-goat.

Anything to make him look less exceptional.

Her friends’ assessment of him has always been that of approval, and many times awe. They talk about what strong arms he’s got, his perfect nose, his well-cut lips and sparkling white teeth—sometimes, too excessively, it made her more jealous than proud.

‘Ogini, what is wrong with you?’ He held her arm now, firm, yet careful not to cause her bucket to fall. ‘Why do you ignore me?’

‘Obinna, hapum aka. Leave me.’ She didn’t stop walking.

He grabbed her bucket. In the season, water has become very precious, so she stopped.

‘Obinna, what is it?’ she said. ‘I said you should leave me alone! Or do you want my bucket to fall?’

Her voice was raised and her face swollen in a frown, but he knew better. Talking in higher voice did not necessarily mean she was angry with him. He never really thought that she was capable of getting truly angry with him anyways.

‘Erm, I think I will be going now,’ Ujunwa muttered. On her face, was that awkward smile of someone who suddenly walked in on a scene of domestic violence.

‘No, Uju stay!’ Ada told her friend.

‘Uju, take your water home. I’m sure Nne will need it now,’ he countered. His eyes were on the girl, the bold eyes that speak only of dominion, dominion most often tempered with gallantry.

‘Yes, yes,’ Ujunwa flung out. ‘Nne had food on fire when I was leaving, I must go now.’

Ada shook her head, aware that her friend has just lied. As Ujunwa walked away, she turned to him with ferocious eyes. ‘Gini, what is it?’

Now he used a voice not even her anger could resist. ‘Obim,’ he called her.

She inhaled deeply and threw away her face.

He carried her bucket from her and lowered it to the ground. He took her hand and drew her gently out of the road.

As she felt the pillar of fury she has spent so much energy to build crumble at the mere sound of his voice, all the hard work gone, she felt like slapping herself, so forcefully she would see stars.

She blamed herself now. She should have run off on sighting him or better still taken the other path that she was sure he wouldn’t follow. Only that she was not so sure of that either; he knew her whole.

It had amazed her the way he easily made her weak. Vulnerable, like a cornered rodent.

She was the strong kind of beautiful girls. The kind that knows how to handle her admirers, no matter in what number, age or size they come. She’d rather confront them than dodge them.

He was the only one capable of crumbling her defences, with things as easy as a single word, or just a calculated stare!

With a bit of regret, she has finally come to accept things as they were. But that does not mean she had given up trying anyway—she is still Adaku, after all.

‘Ada, what is it?’ He was staring at her. ‘Tell me.’

‘I told you to leave me alone,’ she said.

His face changed. ‘You are really angry with me,’ he said.

She took away her face, clucking and blinking hard.

He held her at the shoulders. ‘Gwa m, tell me please. What is it?’

She wanted to speak, but two girls were upon them.

They were carrying plastic jerry cans instead of buckets—tall, slender, yellow cans that once were containers for cooking oil.

Unlike the other people that had to suffer a long queue to fetch, Ada fetched from the tap inside the compound.

Chief Ozua, the short, stocky man that built the borehole, had wanted to marry her at some time.

She had refused, but according to the wealthy chief, she had refused differently—maturely in his own terms— and they became friends afterwards.

‘Dalu kwanu,’ the girls chorused, their eyes gliding past them with feigned disinterest.

Ada was sure they would gossip, but she didn’t care. And neither did him. Their gossip has become too common it has now turned tasteless.

The tale of the two children deceiving themselves with what they did not understand used to be a hot topic everyone in Obeledu was interested in. Some called it infatuation, others mere madness of youth.

But overtime, as more and more mouths continued to taste it, the matter turned flat.

Ada looked back, another woman was trudging up the road with a mighty bowl that screamed greed on her head. The tap has started to run eventually, she could see now. ‘Let’s go,’ she said to him.

He gave an understanding nod and bent to lift her bucket. She placed her aju cloth on his shaved head and he dropped the bucket on it.

That night they met under the avocado tree behind her house.

That was where they first had it, deep knowledge of themselves. He had pestered her about it for months, and that night she came with an extra wrapper. She didn’t say anything to him. She just spread the wrapper on the ground and allowed him.

He had been grateful.

‘So tell me, what got you so upset this evening,’ he asked. She was leaning to the tree while he stood facing her. He smelt of the floral scent of bathing soap.

‘When were you going to tell me?’ she said.

‘Tell you what?’

She turned suddenly to him as if enraged at his pretence of lack of knowledge. ‘That you are leaving for the city, Obinna!’

It wasn’t her intention that much concern showed in her voice. She decided to go on nonetheless. ‘You are not going to Enugu, or Onitsha, or Asaba, you are going to Lagos, Obinna, all the way to Lagos!’

Guilt splashed over his eyes and for once they lost their boldness and dimmed. ‘Who told you that?’

‘Is that what you are going to ask me now?’

He quickly took her arm. ‘Don’t be that way, I am not sure I’m going anywhere yet. Yes, Mama talked to Ahanna, but no agreement has been reached yet.’

She quietly slipped out of his grip. ‘Obinna, your brother sounded so sure so do not lie to me.’

‘Forget that one, he is just over excited.’

‘And you are not?’

‘I can’t be.’

She was quiet.

He took her hand again. ‘How can I be, Ada? How can I even feel normal that I’m leaving you?’

‘So you are really sure that you are going then?’

Feeling caught, he didn’t say another word.

‘Ada, come,’ he finally said. He folded her up in his arms.

She let him.

She always liked that part. Many months of carting away goods at the Nkwo market has gotten his arms bigger, his thighs firmer and his chest, broader, with that embellishing sprinkle of hair. He was what comes to mind when one mentions a strong, sexy man.

‘You must understand why I need to do this. It’s been over four years now since we finished secondary school. I have no hope of writing JAMB, let alone someday going to the university.’

She turned her eyes up at him. ‘Obinna, you are losing hope already?’

He snorted, a faint smile lingering on his face. His excellent dentition afforded him a nice masculine smile. When he smiled broadly, he created the impression of a toothpaste commercial. ‘Those were only childhood dreams, Obim, it was never meant to happen.’

‘Who said?’

‘Me becoming a lawyer?’ He threw out a laugh that meant more than amusement.

She appeared puzzled. ‘Why do you laugh?’

‘Even if miracle happened and I somehow found myself in UNIZIK or UNN, what kind of lawyer do you think I will be when I can’t even speak good English? Eh? Charge and Bail?’

She frowned at him. ‘Didn’t you pass English in your WAEC?’

‘I did. A miracle I still owe you for.’

‘Did I write the essays for you?’

‘You told me what to write.’

‘Then, is that not what the university is there for? The teachers tell you what to do and you do them, is that not it?’

He appeared to consider this for a while.

She stared at him.

‘I heard they are not called teachers in the university though,’ he came through at last.

‘Teachers, lecturers, all the same.’

He smiled at her and hummed. He turned her fully to himself so that they now faced each other. ‘Forget about me. The university was never meant for people like me.’ He brought his face down to hers so that their foreheads met. ‘Don’t you think you can get enough education for the both of us?’

She smiled to that— a sudden smile that seemed automatic. Somehow, the statement settled her. The way he’d used ‘us’.

Then it hit her again—he was leaving. To Lagos! ‘There won’t be any us anymore when you leave for Lagos,’ she told him, shifting.

He did not fake his shocked face—she knew. ‘What do you mean by that?’ he asked.

‘You are going to Lagos to meet those Lagos girls that wear tight trousers and draw scary tattoos on their laps and breasts, who do you think is going to stay here alone and wait for you?’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘What I’m saying is that once your bus to Lagos leaves, I’m going to choose any of my numerous suitors and get married.’

His heart started to beat faster.

She seemed aware of his torment. She continued nonetheless. ‘Who is it going to be now sef?’ She narrowed her eyes, pretending to be in thought. ‘Okwudili? No.’ She shook her head. ‘Okwudili lives in Asaba. I don’t trust those boys in Asaba. He must have gone to drink from the mighty breast. Evil money, kpa. Maybe Chuka?’

She shook her head again. ‘Chuka that stays in Onitsha and says Bebe instead of Baby. I think I’ll prefer someone educated. Yes, Mathew. Someone like Mathew, heard he is in the university again, for the second time, studying for his masters—’

‘Stop!’ he gave out. ‘Stop this rubbish, Ada!’

She obeyed at once, obviously been waiting for the reaction.

‘You are not marrying anybody except me!’ he said.

She liked the authority in the words, but she wasn’t done yet. ‘I am not marrying any man from Lagos,’ she said.

‘What is that supposed to mean? Do I come from Lagos?’

‘I mean once you travel to Lagos, consider whatever we have meaningless.’

‘Ada, stop this. Your words are hurting me.’ His voice was now low.

She turned away, a strange feeling of satisfaction clouding over her. She was happy to know he still cared just as much.

He came to her. ‘How can you be saying these things to me, eh?’ She heard him swallow. ‘Why? Have you no mercy for my heart?’

She didn’t say a word.

‘Ada?’ He waited, but still nothing came from her.

‘Ok, fine! I’m no more going to Lagos,’ he said. ‘I will stay here and we get married in this village and start up whatever life we can manage here.’

She turned to him, a look of compassion on her now. ‘You can go to Lagos,’ she told him. She joined her fingers together. ‘I will wait for you here. I’m just afraid, that’s all.’

‘Afraid of what?’ He took her wriggling fingers, separated them and joined them to his. ‘That I may leave you for some Lagos girl who wear same clothes I wear and greet people by joining lips together?’

She nearly smiled. ‘We have never stayed away from each other, you know that. Are you not worried?’

He exhaled deeply. ‘I am, Ada,’ he admitted. ‘I really am, but Ahanna said if I work hard enough, I can get my own place in less than two years.’

‘So?’

‘So? I will come and pay your bride price and carry you to the city.’

She liked the way he said carry. She imagined herself on his strong, muscular back all the way to Lagos. ‘I might be in school by then,’ she said.

‘There are better universities in Lagos. Haven’t you heard of UNILAGOS?’

She smiled. ‘I want to go to UNIZIK.’

‘Why? Is the education there better?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Anyhow, there must be a way.’

There he goes again. She slipped half of her lower lip into her mouth.

She never liked that he was not the one to reason deeply, never considered anything both ways; success and failure. He was always quick to pick the former.

Sometimes, it made her think of him as scared, though most other times brave— the times everyone seemed uncertain and without hope and he would appear the only one still strong in heart.

Like the day he saved Echezona from the well. When the little boy fell in, the echo of his scream disappearing with him into the deep pit, everyone was running helter-skelter, full of confusion.

But he seemed very much in control when he reached for the tall bamboo. Even after the third dip and the stick still came out without the boy, he continued trying, as though he was sure that something was going to happen eventually.

Success would eventually come.

And he finally saved the day.

She drew near and nestled against his chest.

‘All will be well,’ he told her and folded her up.

Chapter Two

Ahanna sold clothes at Oshodi market in Lagos.

He told Obinna that all he needed was just N30, 000 to start. He’d be travelling to Cotonou with him to buy the clothes.

‘Clothes are so cheap there [Cotonou] you’d wonder if they are made of sand,’ he said to Obinna. ‘But once you enter Lagos, you must shine your eyes. To survive, you must be as sharp-eyed as a hawk. I ga epu anya ka nkwo!’

Obinna had stayed quiet all the while Ahanna talked about Lagos, with a faint look of anticipation on his face, as though afraid to show Ahanna how disturbed the stories about Lagos has made him.

Ahanna told him about Area Boys, ‘ndi nwe obodo’—street owners—as he described them, who sit in clusters all around the place causing mischief and extorting money from people, about the traffic that could hold one for hours, the omoniles’ who came to pull down people’s structures when they did not settle them for the land they bought.

Obinna’s jaw dropped when Ahanna mentioned this. ‘Chelukwa, nwanne—wait, brother, are you telling me that after buying land, you must settle some people before building on it?’

‘Dey there na!’ Ahanna said in pidgin.

Obinna understood his pidgin, but could not speak it. He thought Ahanna had learned it fast; it was barely four years he left Iruowelle for Lagos.

Then he saw Ahanna smile—grin actually— and immediately had the hope of hearing now the good things about Lagos, praying they far outweigh the near horrifying ones he’d already heard.

‘But ashi dey o!’ Ahanna said. He’d lowered his voice and Obinna knew whatever ashi meant would be bad.

‘What is ashi?’ He too had lowered his voice when he called ashi. They were in his house and although Mama Obinna was in the kitchen at the far end of the backyard, her good hearing was legendary.

‘Ashi na…ashawo dem!’

Finally, the horror slapped Obinna’s cavities open.

He’d heard the sickening tales of ashawos before— rotten girls who stood half-naked on the streets at night selling not leather or plastic, but their bodies.

He’d heard their stories from Father Jude during one of his soporific sermons, Mama Ozioma during a gossip about her young cousin who had just returned from Lagos wearing trousers, and then Teacher Nwokolo, and even Principal Eze at the Community Grammar School.

But it wasn’t the mentioning of prostitutes that got Obinna so very shocked, it was the large smile on Ahanna’s face when he said it, the show of great happiness, as though ashawos were a rare precious gift God has blessed Lagos with.

And now he began to wonder what Lagos really is, what it does to people.

Four years ago, Ahanna would never had as much as shown a single teeth at the mentioning of prostitutes.

He’d have pitched a long hiss and curse and curse. But now, with that smile, it was obvious, he too may have patronized them, or even be a regular customer.

Mama Obinna appeared with the tray. ‘Ngwa, food is ready,’ she said.

She used her foot to pull a stool nearby to their front. She placed the tray on it. ‘Let me bring water to wash your hands with.’

Ahanna rubbed his hands together. ‘Thank you, nne.’

Two plates sat relaxed on the tray. One, the flatter one, had a mound of fufu on it and the other, sizzling egwusi soup.

The vapour rising from the round plate steadily watered Ahanna’s mouth and the urge to start eating before Mama Obinna returned with the water nearly overpowered him.

But Obinna was not very much around. His mind bore a different thought, a heavy one.

‘So you have your own house in Lagos now?’ he asked Ahanna.

Ahanna grinned, the proud smile people used to accept praise. ‘It’s God, my brother.’

Obinna smiled and shook his head, impressed.

Ahanna wondered if Mama Obinna has gone to Ama-Oji to fetch the washing water.

Finally, the plump woman returned with a red bowl half filled with water.

Ahanna thrust his hand into the bowl before Mama Obinna could drop it on the table, carrying it from her.

Obinna watched him devour the fufu, one big ball after another.

Ahanna has dug away half of the whitish mound before Obinna finally washed his hands and joined him.

***

Ahanna’s face puckered as he tried to pick his teeth with a broom stick Mama Obinna had brought for him when he demanded for toothpick. ‘Nnaa, mehn, thanks for the food,’ he said.

Obinna did not respond this time. This was the third time Ahanna would thank him for the food. Now, with a feeling of near dismay, he wondered if there was food in Lagos at all too.

‘So how big is your house?’ he asked.

‘Mm?’

‘Like how many rooms does it have?’

‘Rooms?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh, rooms. You will see when we get there.’

Obinna inhaled deeply.

***

Adaku felt different.

For once in her life, she felt out of control. Emotions whirled up inside her in turbulent currents.

Emotions she hardly recognized, let alone knew how to tackle.

It was her Obinna that was leaving, leaving her to Lagos.

Now, all of Lagos she could picture was an enclosed space, room-size or a little larger, filled with women, women of all ages desperate for men, men like Obinna.

Handsome men. Tall men. Strong men. Men with a nice smile and beautifully-set eyes.

Now the door of the room open slowly and Obinna walked in.

The women screamed, running to him. In a matter of minutes, they had devoured him, leaving him unhealthily thin. Skeletal.

She shuddered and commanded herself to be still, to take charge and be in control. Like always.

But her inner strength obviously failed her, and a moment later she was deep in thought again.

Her mother’s voice jolted her back to life.

‘Ada!’

‘Adaku!’

‘Maa!’

‘So we won’t eat tonight, okwia?’

Even though Uchechi was at the other end of the compound, a sizable distance from the veranda where Adaku was sitting, her voice seemed to cause the ground below Adaku’s feet to vibrate.

Uchechi was a large woman. But because she was tall enough with proportional distribution of flesh, people did not easily call her fat. Adaku had her mother’s curves, only shorter.

Uchechi often teased her that whoever was going to marry her would pay double for her bride price.

Whenever Uchechi said that, Adaku would picture herself tying a wrapper above her chest like a married woman, sweeping at Obinna’s compound or preparing his food, while humming gently to ‘Dim o – dim o – dim o!’

Her mother was coming close. ‘This girl, I said, won’t we eat tonight?’

‘Mama, we will.’

‘By sitting there all day holding your chin like someone whose suitors did not come as promised?’

Adaku’s eyes ran up to her mother.

‘The fire is not even up yet. Binie, go and make the fire and let me bring yam.’

She turned and started toward the barn. Adaku got up, untied the wrapper above her blue gown, tied it back firmer and dragged toward the kitchen.

‘Ugochi, bring me matches!’ she called.

‘I’m busy!’ Ugochi’s thin voice came from the sitting room.

‘If I meet you there, eh…if…’ Adaku had turned to head indoors when Ugochi appeared at the doorway with a box of matches, a big frown on her face.

Adaku jerked the matchbox from her. ‘Anu ofia—wild animal!’

Ugochi murmured something before turning back inside.

‘That’s your business! Hope the soup pot is clean otherwise that your pointy mouth will depart from you this evening.’

Later that night…

‘Papa, I need money for my JAMB form.’

Papa Adaku dropped his ball of yam fufu back into the soup and turned to his daughter. ‘JAMB form?’

Adaku nodded.

Now even Uchechi was staring at Adaku. ‘So what happened to marriage?’ she asked.

Ugochi laughed. ‘Obinna is travelling to the big city and now she suddenly remembers school.’

She was on to another laugh when Adaku’s palm met her cheek with tremendous force. The laughter died prematurely. Slowly, it was replaced by muffled sobbing.

Ekene started to laugh.

Ugochi tweaked his ears.

‘Ayi!’ the little boy groaned.

‘Ugochi, Ekene, go inside,’ Papa Adaku said.

He exchanged glances with his wife, that brief eye contact peculiar to parents that bore deep communication.

As the door banged shut behind Ugochi and her little brother, Adaku knew what must be done. ‘I’m sorry, Papa. I…’

‘Why do you suddenly change your mind?’ her father cut in.

Adaku was not happy. She’d preferred her father talked about it, scolded her or even punished her.

Gone were the days she enjoyed her father’s excessive indulgence.

She was an only child for long. Ugochi arrived when she was already seven, and Ekene two years after.

Even now that she was only some months to nineteen, she knew the connection she had with her father hadn’t changed any bit.

She had remained her father’s favourite.

That had been the reason when she told him that she’d want to get married first and then go to school from her husband’s house, with her husband, Mr Onochie’s protest lasted only a few days.

He worked at the Local Government; he knew well about the importance of education. But he finally indulged his daughter, like was usual of him.

But now that Obinna has suddenly decided to change the earlier plans, Adaku couldn’t really fathom why she was not furious at him.

Why she had not stored hot water in a flask and then walk to his house and pour it on his head.

‘Adaku,’ her mother called.

‘Mama.’

Uchechi shifted so that she was now closer to her daughter. ‘Something is wrong. Gwa m, what is it?’

‘Nothing, Mama.’ She folded her hands together. ‘I just want to go school.’

‘How much is the form?’ her father cut in, as was his quick manner of speech.

‘Four thousand five, Papa.’

‘Remind me tomorrow morning and I will give you the money.’

‘Papa, dalu.’

They finished their meal in silence.

Later that night, Uchechi knocked and entered her room. She tied her wrapper above her breasts and she smelled pleasantly of cream and talc. Her neck was white with it.

Adaku rose and shifted for her to sit.

‘Ada.’ She felt her forehead. ‘O eziokwu— is it true?’

‘What, Mama?’

‘That Obinna is travelling to the big city.’

She inhaled deeply. Her mother’s eyes remained on her. And she finally nodded.

And at that moment, the sadness hit her like a blow. She swallowed hard, but she didn’t push it down. It sprang back up her throat with great force and she began to cry. Her mother clutched her to herself.

‘Kwusi, inu—stop. Ozugo—it’s ok.’

They remained in embrace till her sobbing subsided. Her mother released her.

‘Everything will be fine,’ she told her as she rubbed off her tears. ‘All will be well.’

She kept nodding to each word, as though the more religiously she nodded would mean the more certain that her mother’s words came true; that all became fine.

Obinna would cancel his trip. That it was announced on the radio that Lagos has become too filled it could no longer accept any more people.

When her mother left, she lay back into the soft mattress and cried some more before drifting into the unawareness of sleep.

###

Chapter Three and Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen and Fifteen

End of Book One

***

Get all complete stories by Daniel Nkado on DNB Store, OkadaBooks or BamBooks!

Wow…And dey did it? Hmmm sure say jr nevr entr…just hope he won't leave her for all doz tiny legged lagos galz..hehehe

Admin, hw far nah. ..u nevr approve ma comment finish?

Approved now. Oya begin dance #shoki

But Lagos have too wicked on many dreamers! Hope that these skimpy girls will not sweep him off his feet!

I love it plz continue

Obim, it makes my heart somersault,

obinnaya, every woman's dream. Nice one.

pls all dis igbo language Wey una dey use, can u subtitle it in English at the end of each story for non ibo speakers like me. Understand few bt nt all. Biko!

Ok, Sekinat. That'd be taken care of.

Obinna dnt 4get Ada when u get to Lagos o

Hmmmm am now in love!

Omo, they did the thing o. Under a tree on a wrapper!!!! Sweet bush sex

Hehehe….oga vicky na u b admin?

As in eeh, can imagine d leaves nd grasses chuking dem 4sme places

Hahahaha! Vicky ke

She made the biggest mistake of her life for me having sex fircd first time with a guy u know is going to lagos did they use condim..n oga lagos is nt a bed of roses bcos of pple with such mentality able bodied mam dah re meant to b in farm re in lagos unemployed n involve themselves in diff vices like stealing killing kidnapping rape..pls stay in d village n farm lagos is nt for all

Ha! Una don spoil finish. So datz d only tin u pple read? Lolz

Pamscrib.blogspot.com

Glad. Supu of. Speak out. Lolz

Nice. I love where this is going.

Pamscrib.blogspot.com

Lmao, Emmanuel done vex o.

@eyej, what is vicky

Pls let it continue ooooo

Lolzzzzzz

Supu of z wot nau…u too dey brow ur own grammar

vicky abi Wetin, so y re u lafn ur ass out. …lyk u cn speak bera dan hm

we shld b encouraging if we wan ds blog to grow

emma no mind dm

Supu ya means speak out. The "of" there was supposed to be "ya", don't mind autocorrect.

"Supu ya" is igbo language.