by San Pashtun

On January 6, 1995, a large five-foot-six 270-pound middle-aged man robbed two Pittsburgh banks in broad daylight.

He didn’t wear a mask or any sort of disguise. And he smiled at surveillance cameras before walking out of each bank.

Later that night, police arrested a surprised McArthur Wheeler.

When they showed him the surveillance tapes, Mr. Wheeler stared in disbelief. “But I wore the juice,” he mumbled.

Apparently, Mr. Wheeler thought that rubbing lemon juice on his skin would render him invisible to videotape cameras.

After all, lemon juice is used as invisible ink, so as long as he didn’t come near a heat source, he should have been completely invisible.

Police concluded that Mr. Wheeler was not crazy or on drugs — just ridiculously mistaken.

The unfortunate affairs of Mr. Wheeler inspired a series of psychological studies by Professor David Dunning of Cornell University and his graduate student Justin Kruger.

They reasoned that almost everyone holds favorable views of their abilities in various social and intellectual domains.

However, some people are unaware of their lack of abilities and mistakenly assess their abilities as much higher than they actually are.

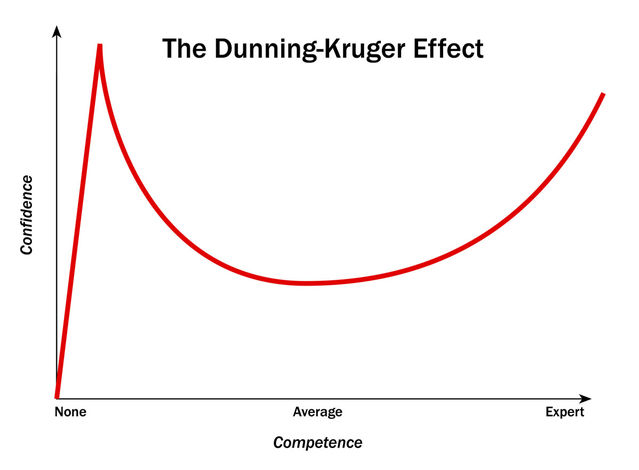

This ‘illusion of confidence’ is called the ‘Dunning-Kruger effect’ and describes the cognitive bias to inflate self-assessment.

To investigate this phenomenon in the lab, Dunning and Kruger designed some clever experiments.

In one study, they asked undergraduate students a series of questions about grammar, logic, and jokes, and then asked each student to estimate their score overall as well as their relative rank compared to the other students.

Interestingly, students who scored the lowest always overestimated how well they did — by a lot.

Students who scored nearest to the bottom estimated that they had performed better than two-thirds of the other students!

But this ‘illusion of confidence’ extends beyond the classroom.

In another study, Dunning and Kruger left the lab and went to a gun range.

There, they quizzed gun hobbyists about gun safety, and again those who answered the least questions correctly wildly overestimated their knowledge about firearms.

Today, if you watch any talent show on television, you will see the shock on the faces of contestants, who do not make it past auditions and are rejected by the judges.

Sure, it seems almost comical to us, but they are genuinely unaware of how much they have been misled by their illusory superiority.

Whether we are designing a rigorous scientific study or raising children, we depend on knowledge, wisdom, or understanding to be successful and satisfied with the different parts of our lives.

Sometimes we try things that lead to favorable outcomes, but other times – like the lemon juice hypothesis of McArthur Wheeler – our approaches can be imperfect, irrational, inept, or just plain stupid.

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.” — Charles Darwin.

The problem is that when people are incompetent, not only do they reach wrong conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but also they are robbed of the ability to realize their mistakes.

Instead of being confused, perplexed, or thoughtful about their erroneous ways, incompetent people insist their ways are correct.

As Charles Darwin said, “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

A simple example of this is driving ability.

One study found that 80% of drivers rate themselves as above-average drivers.

Similar trends have been found when people rate their relative popularity and cognitive abilities, but illusions of superiority are not always so mundane and can have real consequences.

Consider the anti-vaccination movement.

A group of people with no medical or scientific qualifications are refusing to vaccinate their children for fear of them developing autism.

Even though there is no scientific linkbetween vaccines and autism, their erroneous opinions are so loud and convincing that they have caused the reemergence of diseases that had been previously eradicated in the United States.

Globally, the anti-vaccination movement has caused the resurgence of many treatable diseases, which you can visualize on this interactive map made by the CDC.

We now live in a golden age of rational — or irrational — ignorance.